A Framing Is a Choice of Boundaries

One way or another, you've gotta chop it up.

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Mr. Great Heart, Unsplash

Neo:

What are you trying to tell me? That I can dodge bullets?Morpheus:

No, Neo. I'm trying to tell you that when you're ready, you won't have to.— The Matrix, 1999

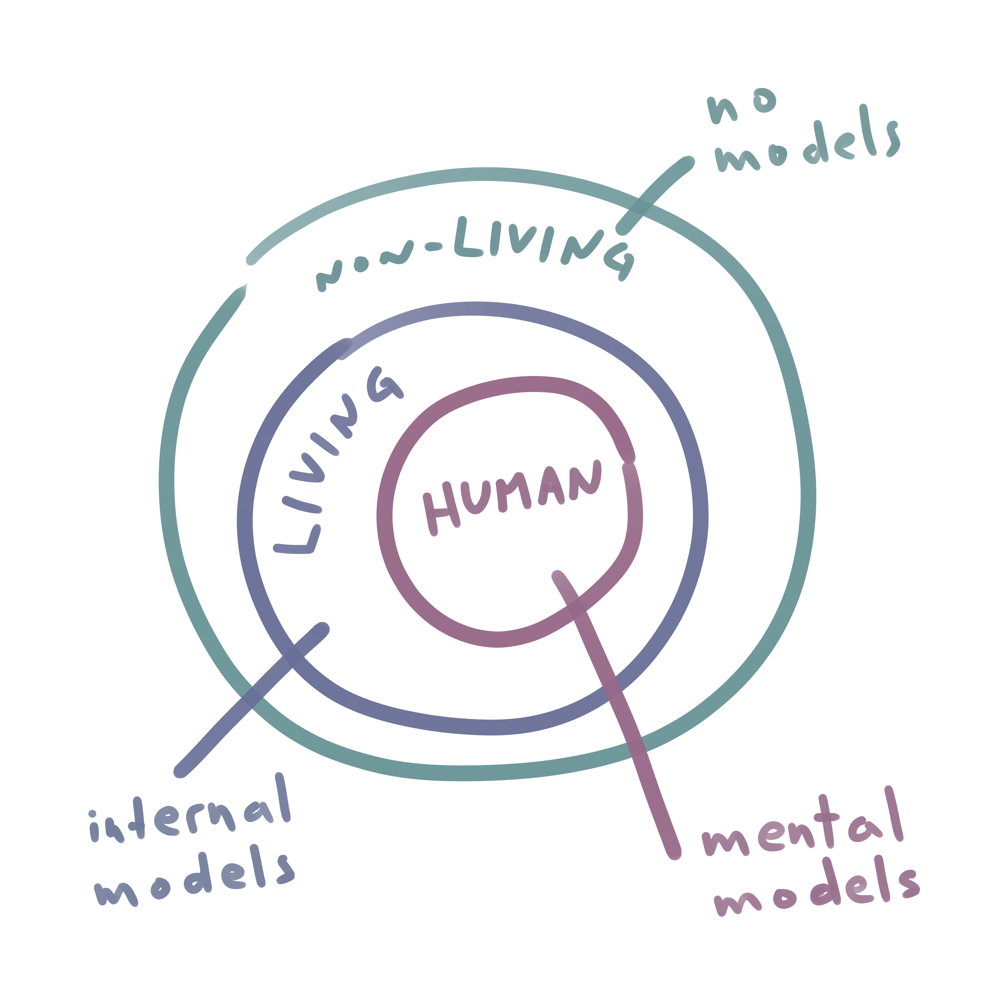

In Embedded Prophesy Devices I wrote about internal models. We, the living organisms, always simulate internally the bits of the external world that matter to us, and act based on the results of our simulations. We take sensory inputs, feed them into our internal models, and see what's likely to happen. It doesn't matter if we have a nervous system or not, a version of this process happens in every living thing, from microbes to insect colonies to tenured university professors.

That last group is especially interesting—not just the professors, but homo sapiens in general. The jury is still out on other animals, but humans certainly have what we can call "mental models", which is a very sophisticated kind of internal model.

It's difficult to reason about mental models, because we usually equate them to the things they're made to simulate: in everyday speech we say "it's going to rain," not ["my mental model predicts rain"], although the latter is arguably more accurate. This conflation of model with reality only happens with mental models, because the "non-mental" kind of model only drives unconscious, automatic behaviors. The moth that flies into a street lamp at night isn't thinking "hmmm, I'm finally making it to the moon!" Instead it acts automatically on the output of its internal simulation, which (implicitly) assumes that the moon is very very far away, so that flying at a fixed angle towards it will allow the moth to fly straight for long distances.

We people, on the other hand, actually think that the world we simulate is nothing but reality. Even though our mental simulations run entirely inside a dark and moist environment covered by flesh and bones, receiving nothing but electrochemical signals from the outside, we somehow convince ourselves that we're experiencing reality directly, whatever that means. Said like that it sounds silly, but hey, it works just fine. In almost everything we do in life, pretending that our models are the actual things they refer to makes everything easier with no big downside.

But there is a subtle catch. By convincing ourselves that we're reasoning about the world directly, we usually fail to see the huge difference in how external reality and mental models of that reality work. Outside, everything follows the laws of physics. Inside, our mental models use simplifications and heuristics to simulate the same patterns.

The thing we call "weather", for example, is a process involving an unimaginable number of interactions all happening at the same time, from the subatomic level to large-scale wind and cloud phenomena. The "weather" model in your brain, however, can't simulate every air molecule bouncing around the atmosphere in order to make predictions about the weather. It doesn't have nearly enough neurons for that, and it doesn't need to. It only tracks a small number of variables, like the color of the sky, the humidity of the air, and especially what the weather app on your smartphone is telling you will happen. Based on these few inputs, your model makes a prediction about what are the most likely things that can happen (in something like a tree of possibilities) and you use that to decide whether you should take your umbrella out with you or not.

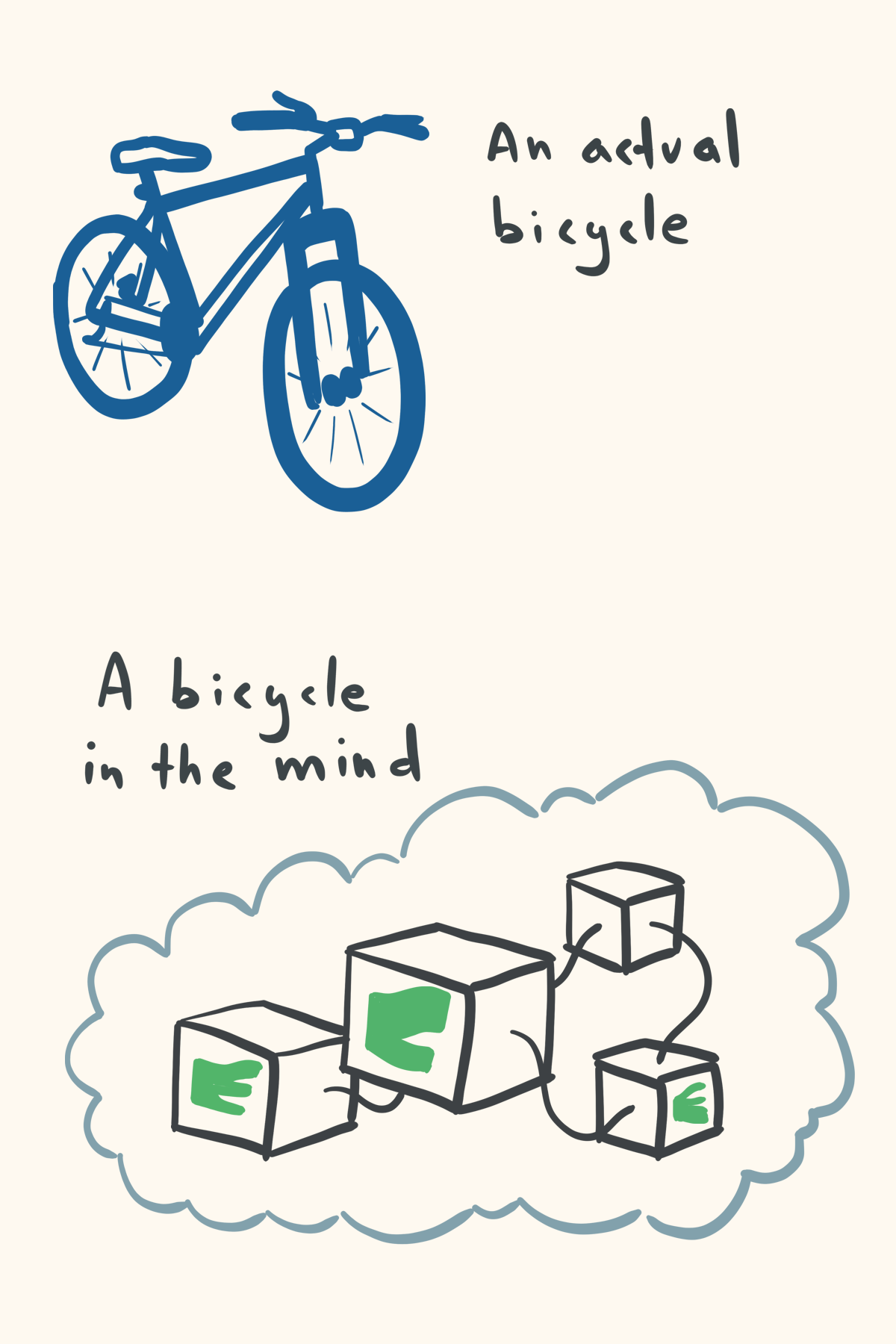

In order to be usable, mental models must reduce most parts of the things they model to structure-less "points" with predefined behavior. Only then can they focus on simulating the interactions between those points, ignoring anything that happens inside them. In other words, mental models are networks of black boxes.

At least, something very close to that must be happening, based on the fragmentary evidence we have from psychology. Strategies to plug models we know well into new models to act as black boxes, like metaphors and analogies, seem to be central to the way we think. And we now know that heuristics play a major role in our perception and decision making. We even have promising theories for the concrete mental process of our simulation of reality.

Seeing mental models as made of black boxes explains a few mysteries:

- Why we can make predictions about systems that result from the interaction of Avogadro-scale numbers of particles.

- Why we imagine riding a car without knowing how it works, or make someone laugh without understanding the neuronal processes of hilarity, or sing without ever having seen a vocal cord.

- Why we tend to see everything as "things" doing stuff, rather than the uninterrupted network of interactions that it really is.

There is a problem with this view: which interactions should we put inside a mental black box, so that we can safely ignore them, and which should we keep as interactions between the black boxes? Or, to put it differently, where should we draw the boundaries between things? Unlike most other species, we have a certain freedom to draw and redraw the boundaries of our black boxes to fine-tune how effectively our mental models simulate reality.

Suppose, for example, that one day you decide to read up on the Israel-Palestine conflict, because you've heard about it a lot but have no idea how something like that might be going on. You might begin with a hazy mental model of "Population 1 black box" (Israel) and "Population 2 black box" (Palestine), each with its religious beliefs and claims to a piece of land. This isn't enough to understand why the conflict could be so violent and bitter and persistent. Can't they just live together in that place, each side minding their own rites? It doesn't make any sense.

Then you read about how Jews have been treated over the centuries, and the way the state of Israel was established in 1948, and how hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were displaced in the process. This leads you to draw a few new lines in your mental model: other countries, like the UK and the US, have had a role in the conflict, so you can't just treat them as part of a generic "rest of the world" black box. You need to have separate a black box for each of them, because their direct interactions with the initial two black boxes is specific and important. Then you might learn that there are factions and organizations within both sides of the conflict—for example the militant organization Hamas, as related to but distinct from the broader Palestinian population. Now you have to split things up again, with a black box for Hamas and another one for the Palestinians who are not directly affiliated with it. And so on and so forth. As you learn more about the geopolitics of the war, you keep on revising your boundaries, on finding new things between which you should be tracking and simulating in order to make better predictions on the matter. Your predictions will never be perfect, but they can be better than before.

We can call a specific choice of boundaries a framing. Every model we use in our heads is built on one framing or another. As with our use of models, framings are absolutely necessary to our interpretation of reality, but we're not often conscious of them. Most of the time, they are invisible to us, like the frame of your glasses becomes invisible after you've worn them long enough. When you assign a name to something—like I just did by defining "framing"—you're updating a framing: you're changing the number and the specifics of the possible interactions you can simulate with your mental models.

New framings pop up when people make important realizations. Before the discovery of plate tectonics, geologists had no reason to divide different parts of the Earth's crust into sub-regions. Everything was one block in their mental models, and as a consequence of that lots of things didn't make sense. Then, over the course of several decades, they acquired a new framing, in which the crust is actually a network of many continent-sized plates, each capable of moving somewhat independently, but all connected to each other with certain mechanisms. New boundaries were drawn inside what used to be the "Earth's crust black box", and suddenly things made more sense: mountain formation, earthquakes, and volcanoes now fit in the framework as different outcomes of the same tectonic processes.

You can see all big scientific revolutions in this light: new "things" or terms were introduced, new relationships and processes extracted out of black boxes and into "plain sight", so that we could employ them in our models (theories). Think about the novel concepts of "germ" and "immune system" introduced by the Germ Theory of Disease, and the words "natural selection" and "fitness" that Darwin drew up, and so on. In every case, new boundaries led to new interactions being examined, and better models of reality.

Sometimes two framings seem to differ not in where you're drawing the boundaries between black boxes, but in the relationships between those black boxes. The "glass half full" vs "half empty" trope is really about two different framings that draw the same water/air boundary, but give different causal powers to each side of that boundary. Is it the water-filled part of the glass that is more consequential, with your ability to drink it and hydrate yourself, or is it the empty part that you should focus on, as an omen of what is unavailable to you?

I think that these are still different ways to draw boundaries. Locally, when you look only at the glass, it appears as if the water/air surface is the same in both the pessimistic and the optimistic views. But expand your field of view and you'll find that those are but little segments of a much bigger boundary, one that encompasses very different things in each case.

The "half-full" view draws a boundary around myriad things and events that to you, taken together, mean that life is full of opportunities. In this view, the other things outside of that boundary are separate things, devoid of an overarching meaning or coherent powers. When you see the glass as half full, the empty half is "just a bit of air", with no relation to yesterday's inopportune downpour or to your flat tire this morning. On the other hand, a pessimist sees the half-empty part of the glass, the rain, and the flat tire as parts of the same black box—one that is working against them to make them unhappy—and the water in the glass is "just a bit of water", unable on its own to comfort them even a little.

Another example of a boundary that seems to stay the same is the difference between the heliocentric and the geocentric models of the solar system. You could argue that Copernicus introduced no new "things", no new black boxes to simulate independently. The Sun-Earth boundary appears to have remained the same, and only the way the sun and earth relate to each other has changed. But what Copernicus did was to say, "hey, the line surrounding the things we call "planets" should include the Earth too, because it does the same kind of things Venus and Mars and the other ones do; but it shouldn't go around the Sun, as it's a different kind of beast". In other words, the Earth and the Sun swapped places around the boundary. That's to show how tricky it can be to examine and reason about our framings, let alone change them into something "better".

And, by the way, how can a framing be "better" or even just "good"? If they are all subjective simplifications and projections onto reality of boundaries that don't really exist, does it make sense to say that a framing is, in absolute terms, "good" or "bad", "true" or "false", "right" or "wrong"?

No, in fact, I don't think it makes sense. How you draw the lines is up to you, and it has nothing to do with morality or accuracy. But a framing can be more or less effective at achieving a given goal. A framing is effective if and when it lets you pick out meaningful differences that you would otherwise overlook. You judge it by how well and how easily it lets you simulate the parts of reality you want to predict. Even when looking at the same corner of reality, another person, with different goals, might find a different framing to be more effective.

I'll repeat that. The way you chop up reality into black boxes has huge consequences for the way your models will work and what they'll predict, but it is subjective and arbitrary. How "good" a framing is depends entirely on what your purpose is when you use it.

So if you find yourself baffled by the arguments of someone disagreeing with you, chances are that the two of you are thinking off of different framings. And, more often than not, your framings are different not (necessarily) because one of you is stupid, but because you have different goals. In that sense, you might be both right within your respective framings, and it's pointless to argue very long about what your models predict: align on the goals first, and the framings might synchronize on their own. Framings are tools for us to manipulate.

If you don't realize you're using a framing, you can't even begin to understand its limitations, not to mention improve it. Reality is whatever is out there beyond your cranium walls, impossibly far and dim, and you can only hope to learn a little about what it was like in the past. What feels like reality to you, on the other hand, exists only in your mind, and you—being human—have the ability to partly modify the way it works. The upshot of that knowledge is that it might spare you the need to dodge bullets. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Mr. Great Heart, Unsplash