A Kanji Always Pays Her Debts

In defense of steep learning curve

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Ryunosuke Kikuno, Unsplash

I often find myself having to take an elevator in a sparsely-populated wing of a medical research facility. When I do, I go up and down more than a dozen floors completely alone, because no one else ever seems to use that specific elevator. So I stand there in the metal box and I look around for something to contemplate, and my eyes fall on this elegant floor guide beside the doors.

It's beautiful, and its contents are fascinating. It is essentially a Japanese-English dictionary of medical disciplines. The thing that captures my attention is how differently these two writing approaches work for unfamiliar words. Most of those English-language terms are somewhat familiar to me, but I'm fuzzy on the meaning of some of them. There is one that, at first, I have no idea what it is about: "cytoarchitectonics". It must have something to do with architecture, but what of?

Fortunately, I can peek at the five kanji 細胞構築学 written next to the English word, and instantly everything is clear. These are all easy kanji that Japanese children learn early on, and that I've seen myself many times before. Here, the Japanese term is actually made of three common "words" (actually, the first two are "compounds", combinations of characters, and the third is a standalone character):

- 細胞 (saibou, cell),

- 構築 (kouchiku, construction), and

- 学 (gaku, "discipline").

It must be the study of how cells are built and structured!

If the English term carved in the wooden panel had been "cell architectonics", it would have had the same clarity as the Japanese. Instead, it was cytoarchitectonics, a rather scary word. Looking that up, the "cyto-" prefix comes from the Ancient Greek word kútos, meaning "container". Now that I think about it, that prefix is used a lot in biology to mean "cell"—for example cytoplasm, the contents of a cell, and cytoskeleton, the protein filaments that give shape and solidity to a cell. But the link between cytoarchitectonics and those other terms didn't occur to me in the elevator, and I'm not very well versed in Ancient Greek.

This is a small peek into why I think scripts using Chinese characters are more effective than some people give them credit for.

There are, of course, many who love kanji and hanzi, but I've often heard the claim that these writing systems are—at best—quaint relics of the past, over-complicated and poorly adapted to our modern needs. At worst, they hold back the cultures that use them, and should be abolished in favor of more "efficient" systems like an alphabet or the Korean hangul.

I'm not going to argue against the power of phonetic systems. Their versatility and extreme learnability needs no defense. Hangul are fantastic: simple, unambiguous, and nearly as beautiful as old-style Chinese characters themselves. The point I want to make is another one: practically speaking, kanji have clear downsides in their numbers and complexity, but those same properties offer benefits that cannot be replicated by phonetic symbols alone.

Here is why.

(Most of what follows holds, of course, for the hanzi characters used in China—but I'll stick to Japanese because that's what I know.)

Open-Book Etymology

The Japanese word for cytoarchitectonics was more helpful than its English counterpart, and that is not a coincidence. Once you've done the hard work of learning the most common two to three thousand kanji, you'll find that you're able to infer the meaning of most compound words, even those you have never seen before.

Try this game yourself. Look at the following list of terms from the floor guide (without peeking at the photo!), and the meaning of the individual characters that compose them.

| Japanese | Meaning of Each Kanji | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 免疫学 | discipline of + avoid + diseases |

| 2 | 法医学 | discipline of + law + medic |

| 3 | 病理学 | discipline of + sickness + rules |

| 4 | 病理診断学 | discipline of + sickness + rules + [medical examination] + decide |

| 5 | 生体構造学 | discipline of + living + body + [structure] |

| 6 | 生理学 | discipline of + living + rules |

(The terms in square brackets are commonplace Japanese compounds themselves, so I give the meaning of the whole compound for those).

Then try to guess to which of the shuffled English terms that follow they correspond. If you don't know what those words mean in English, feel free to look them up on Wikipedia.

| English | |

|---|---|

| A | Forensic Medicine |

| B | Structural Biology |

| C | Immunology |

| D | Physiology |

| E | Diagnostic Pathology |

| F | Pathology |

The answer of what corresponds to what is at the bottom of this page.

How did it go? Note how you don't need to be able to pronounce those words to extract their meaning. This realization should give a bit of relief to beginning Japanese learners, who are inevitably daunted by the bonkers number of possible pronunciations for each character.

In other words, if you know the meaning of those characters, they'll offer you the etymology of the compound words that contain them on a silver plate.

In Western languages like English, French, or Italian, there are always several possible ancient sources of meaning you could be dealing with. Taking English as an example, its words could come from Latin, Greek, Anglo-Saxon, Old Norse, Celtic languages, and sometimes a mixture of these. In order to guess the meaning of an unfamiliar word, you would have to pay close attention to how other words you know are composed, distinguish the meanings of those strange prefixes and suffixes, and put them together in the new combination. And that is only if you're lucky enough to be dealing with a word that hasn't been altered or fused together in some contorted way by language evolution.

Compare that with Chinese and Japanese, where the components are atomic blocks of meaning. While their pronunciations may have had as interesting and confusing a history as any English word, the meaning is its own source. Because of their modularity, these logograms don't tend to merge and morph as freely as the sounds in the phonetic systems. The etymology, thus, is often an open book for the reader.

Alternatively, you could say that phonetic writing systems are particularly bad at producing clear, self-evident jargon.

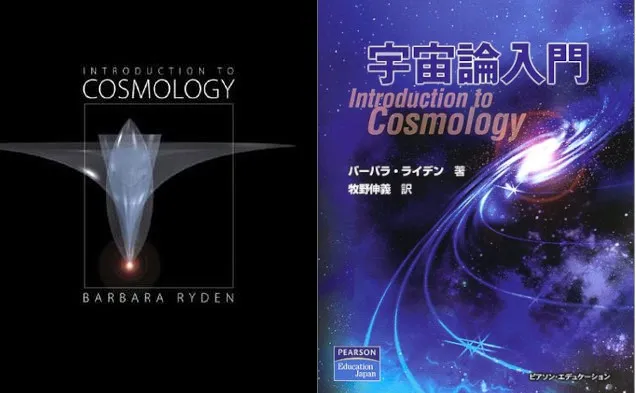

As a side note, this hidden power of kanji is what allowed me to try a rather scary experiment back in graduate school, in Rome. I was almost three years into my Japanese studies, and two years since I had memorized the meanings of the most commonly-used kanji. At the time, I was able to read manga and novels with the help of a dictionary, but I felt I needed a bigger push. A Cosmology exam came up, and the classes—held in Italian—were based on Introduction to Cosmology, a textbook by Barbara Ryden. Of course, we were supposed to buy the book and study it for big exam, consisting of a written test and the kind of oral grill-interrogation typical of Italian universities. When I found out that Ryden's textbook had been translated into Japanese, I couldn't resist. I bought it, thinking I was probably wasting my money, but was surprised to find that all those fancy scientific terms were instantly recognizable from their kanji.

Of course 力学, or "discipline of + force", means "dynamics"! Of course 重力 (weight + force) means "gravity", 星雲 (star + cloud) "nebula", 運動エネルギー (movement + energy) means "kinetic energy" and 等方的 (of + equivalent + directions) means "isotropic"!

I was astonished. I had expected the technical terminology of graduate-level physics to be the main challenge when reading that book, and instead they were entirely intelligible, logical, self-explanatory. If anything, the textbook was easier to read than a novel. I never bothered buying the English version. I studied the whole course on the Japanese book and passed the exam without problems—except perhaps a couple of curious looks from the professor.

Unknown Words

Being able to easily match Japanese and English words like that may seem like a small perk. But the benefits extend to words that don't necessarily have exact equivalents in another tongue.

In most cases, in Japanese you're not even expected to know the rare composite words in a text—unless you want to reuse them yourself. More often than not, the moment you encounter a new compound you have enough context to triangulate with the meaning of its kanji and "get it" without the help of a dictionary.

For example, this is the first sentence of the essay "Chewing Gum" by Terada Torahiko, published in 1932:

銀座を歩いていたら、派手な洋装をした若い女が二人、ハイヒールの足並を揃えて遊弋(ゆうよく)していた。そうして二人とも美しい顔をゆがめてチューインガムをニチャニチャ噛みながら白昼の都大路を闊歩(かっぽ)しているのであった。

While walking in Ginza, I saw two young women dressed in flashy (Western + attire), strutting along in high heels. Both of them were (broad/bold + walk) down the busy streets of the city in broad daylight, their beautiful faces contorted as they chewed gum noisily.

In the translation, I picked two relatively uncommon compounds and replaced them with the meanings of their separate kanji. Someone educated enough to read a daily newspaper would know those characters independently, even if they have never seen them combined in those specific ways. Put like this, I don't think I even need to tell you what those two words "mean". It comes almost for free.

This fact is a boon for intermediate and advanced students of Japanese with a good number of kanji under their belt, because the writing system gives them a lot of help in learning new vocabulary.

Like with all other languages, the reader has the context of what they're reading to constrain the possible meanings of the new word. But, in addition to that, the kanji restrict the space of possibilities even further, often to the level of unambiguous certainty. And, finally, uncommon words usually come with furigana, the pronunciation of the word written in small phonetic script next to the relative kanji. This little package of information teaches you everything you need to know about the word, and it does so in the most effective way possible: as an organic part of living, working language. No one ever needs to learn aseptic word lists for Japanese.

(About the other amazing effects of this meaning/pronunciation duality in Japanese I've written already here.)

Of course, you might occasionally find a character you don't know, as opposed to a novel compound of known characters. In this case you might be stumped, just like you are when you find an unknown word in English. But there are many fewer kanji than there are English words, so this situation is relatively rare as you go beyond the intermediate level.

As far as I understand, this ease of acquiring new "words" exists in Chinese, too, given that it is the original source of this writing approach. But there are many more hanzi characters in circulation in modern Chinese than there are in Japanese, so the experience of being stumped by unknown logograms might be a little more common.

Front-Loading

Saying that meaning-based characters are a more primitive or less efficient form of writing is like trying to argue that humans are more "evolved" than fish.

At a superficial level, it seems obvious: people are much smarter than fish, and an alphabet can be learned with a tiny fraction of the effort that it takes to learn enough kanji. Compare a fourth-grade student in the UK with one in Japan, and you'll find the former able to read out loud—if not fully understand—any book intended for an adult audience, while the latter will get lost very soon in the sea of unknown characters.

But, of course, fish are precisely as "evolved" as humans, and as all the other species currently alive on Earth. We all have an evolutionary history of the same duration, and have always had to adapt and survive in a harsh environment. If fish are dumber than people, it is not because they are more "primitive", but because they don't need to be any smarter to thrive as gloriously as they do in every body of water on the planet. Similarly, the various ways people write today have survived until now because each of them works precisely as it should.

So, learning a gazillion kanji is a PITA. It's a feat that takes time and a good amount of grit even for an adult, while any child has their A-B-C securely in their head before turning 7. This comparison is unfair, though. Learning those gazillion kanji also equips you with a huge amount of modular, consistent "semantic bits" equivalent to what we call words. A more apt comparison, then, would be between learning the kanji, on the one hand, and learning the alphabet plus a few thousands more words on the other.

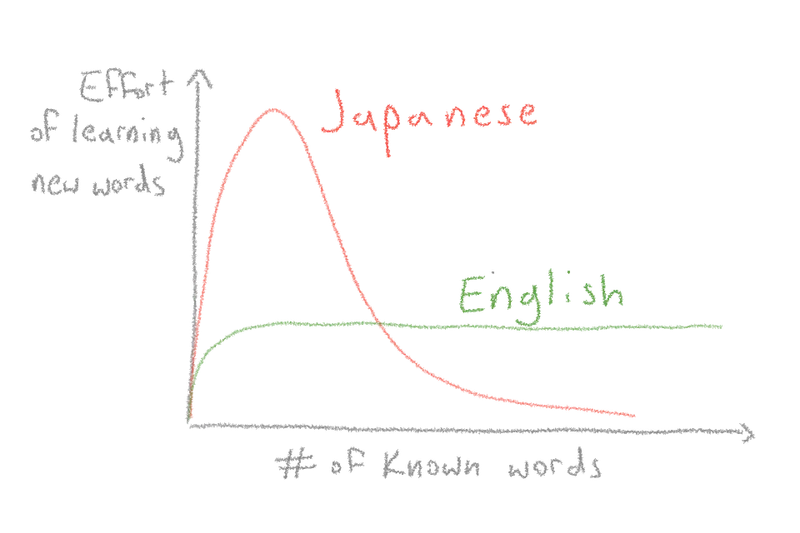

But it's more different than that: knowing the kanji also gives you the toolkit you need to build and parse any number of novel combinations of those symbols, multiplying your reading power. The effort needed to learn new words seems to follow two very different curves for Japanese and <insert alphabet-based language here>:

The effort in Japanese (and Chinese) is heavily front-loaded, but it pays back once you're past the bump. A kanji always pays her debts.

Eventually I reach my destination floor, the elevator's doors open, and I step out. ●

Answers to the word-matching game: 1-C, 2-A, 3-F, 4-E, 5-B, 6-D.

Cover image:

Photo by Ryunosuke Kikuno, Unsplash