Borges on Chaos Theory

About a weird, lovely short story

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

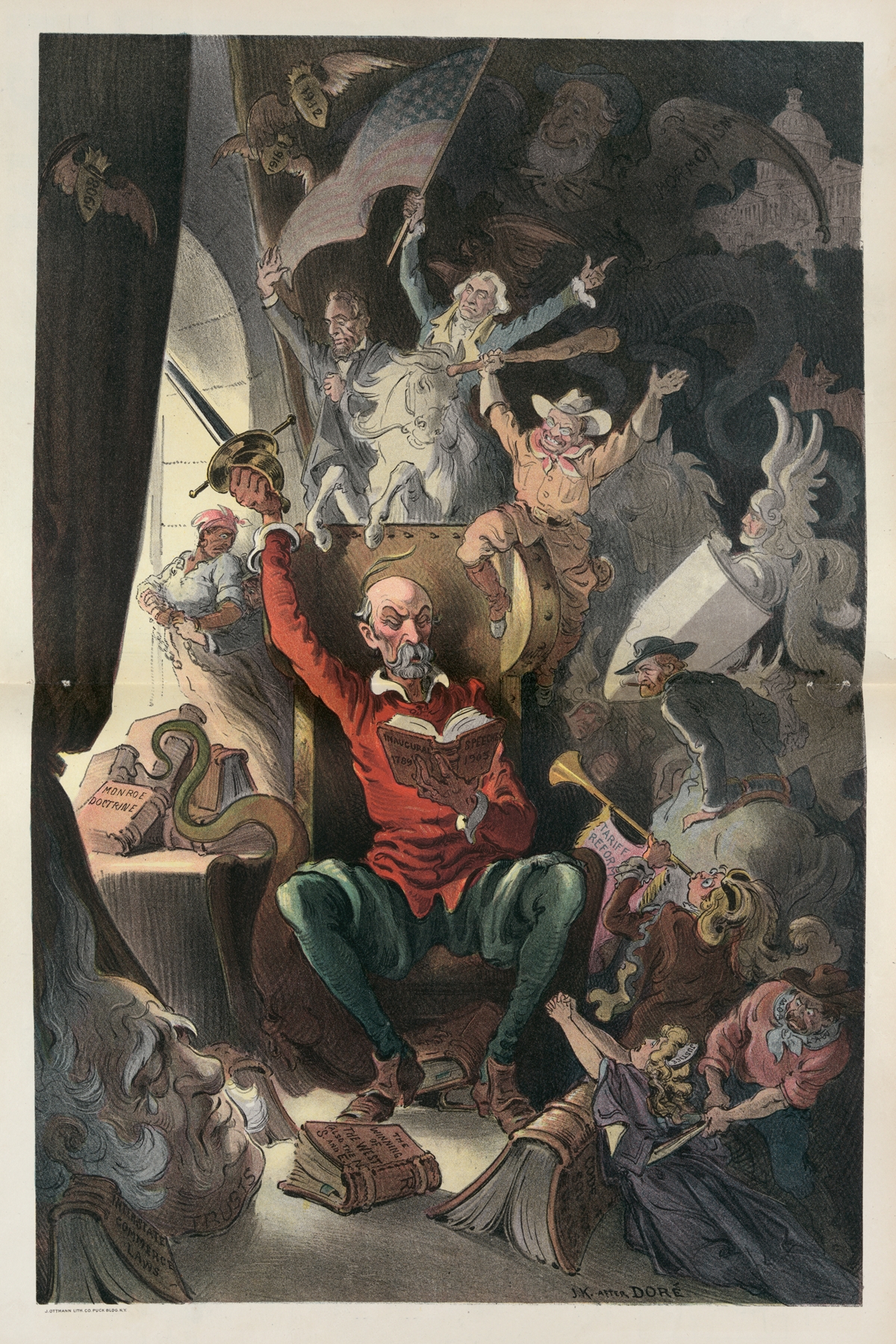

Cover image:

The Hoosier Don Quixote, Udo Keppler

I

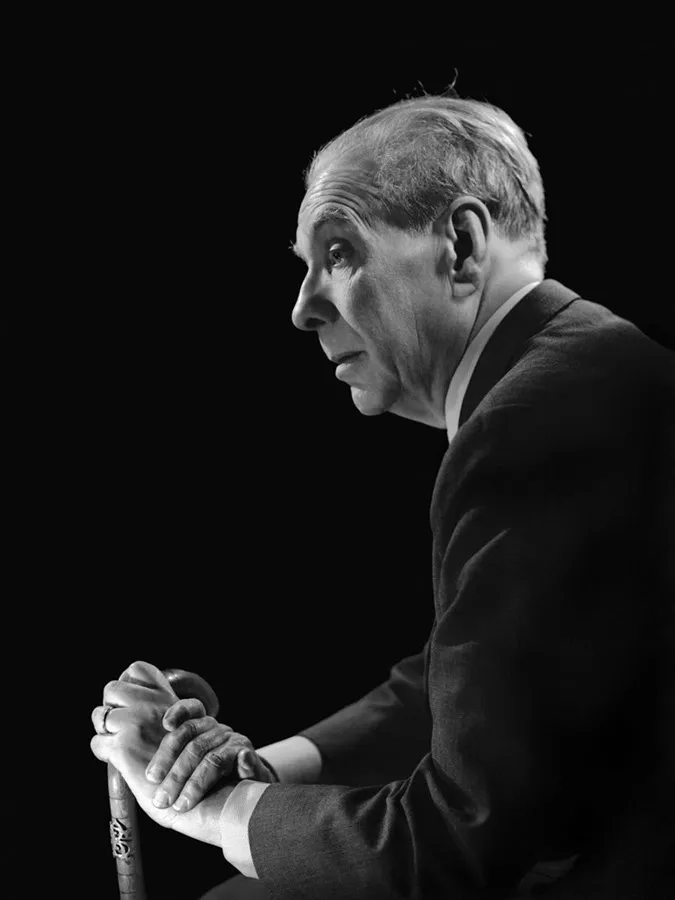

"Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote" is part of a short story collection, and that makes it a short story. But this is no typical story. It has no plot, no setting, no descriptions or dialog, no direct interactions between people, and only one character—or one and a half, if you count the narrator. In other words, it's a kind of story that Jorge Luis Borges excelled at.

I'm an avid reader of short stories, and can easily recall several that have left indelible footprints in my psyche: Hemingway, Poe, Buzzati, Tsutsui, Borges, Borges, Borges. Yet, all things considered, this strange story from 1939 might just be my favorite, one my mind has gone back to time and again since I first read it fifteen or twenty years ago.

Borges was a meta-author (which also means that it's impossible to spoil a Borges story). His "Pierre Menard" follows a pattern shared by many of his other works from the same collection, because it's really a literary essay by an imaginary critic about an imaginary book by an imaginary author. The author in question is the titular Pierre Menard, a French poet and writer who has just passed away, leaving behind a corpus of rather conventional works. But—the narrator laments—Menard's masterpiece, his greatest legacy, is also his most overlooked and misunderstood undertaking: several chapters of the "Don Quixote".

Not a modern reboot of Cervantes' novel, nor a reinterpretation of it, but a new novel written by his modern self that happens to be perfectly identical, word for word, to the original.

Menard explains in a letter to the narrator (translation by Andrew Hurley):

This game of solitaire I play is governed by two polar rules: the first allows me to try out formal or psychological variants; the second forces me to sacrifice them to the “original” text and to come, by irrefutable arguments, to those eradications.

In other words, he arrived at the final form of his text after a proper creative process, in which he strained to express his own ideas, impressions, and themes, as a 20th-century author, only to converge through editing and reasoned re-writing to words that matched exactly those written by Cervantes. This is hard work:

He dedicated his scruples and his nights "lit by midnight oil" to repeating in a foreign tongue a book that already existed. His drafts were endless; he stubbornly corrected, and he ripped up thousands of handwritten pages.

If you're wondering how one would write such a book in practice, you're dancing to Borges' tune. His eight-page treatise is so methodically crafted, so full of erudite digressions and plausible references and even tedious little rants that, before you know it, you've happily suspended your disbelief and accepted Menard's endeavor as something that might happen. Except—this a sign of the author's true genius—you're never fully committed to the idea, and are left thinking and wondering, in a corner of your mind, how one would write such a book in practice, and what it would be like to read it. That thin gap between what the story is saying and what you're willing to believe is the first layer of Borges' magical irony.

The French author's efforts, anyway, seem to pay off. According to the narrator,

Menard's fragmentary Quixote is more subtle than Cervantes'. Cervantes crudely juxtaposes the humble provincial reality of his country against the fantasies of the romance, while Menard chooses as his 'reality' the land of Carmen during the century that saw the Battle of Lepanto and the plays of Lope de Vega.

A choice that, in the 20th century, is not obvious and must have a deeper meaning.

Moreover, other modern authors of historical fiction, writing about those times, would have indulged in colorful stereotypes and romanticism (says the narrator) but in Menard's work there are "no gypsy goings-on or conquistadors or mystics or Philip IIs or autos da fé. He ignores, overlooks—or banishes—local color. That disdain posits a new meaning for the 'historical novel.'" (How does one not chuckle here?)

The story goes on to analyze some passages of both works, comparing the 1602 version with the Menard one, contrasting their philosophical messages, stylistic quirks, and influences (e.g. years as a soldier in the Spanish Navy on one side, Nietzsche on the other). All, of course, while providing pairs of absolutely identical quotations.

Scholars (the non-imaginary kind) have explained "Paul Menard" as a humorous critique of literary criticism and the meaning of authorship, and a statement about the role of the reader in creating meaning. The short story ends with the narrator's claim that Menard invented a whole new way to read, one where you deliberately imagine the text as written at a different time and by a different author, leading to radically different interpretations of the original text.

I think the scholars are right, and that's all very interesting. But the reason I love this story is that I see in it another layer, one that has to do with the chaotic nature of reality. And I mean that literally: it's a story (also) about the scientific Theory of Chaos.

II

Although they use the same words, the Don Quixote of Cervantes and that of Menard exist in very different contexts:

Not for nothing have three hundred years elapsed, freighted with the most complex events. Among those events, to mention but one, is the Quixote itself.

The difference of everything that happened in those three hundred years, along with the different culture (Menard is French, not Spanish) gives the hypothetical Quixote a completely different meaning. Another context, another meaning.

Borges didn't invent that from scratch. The same thing happens so often that we've stopped noticing it. Take, for example, proverbs (watch just the first 3-4 scenes):

Every time we intone a proverb like that, we're faithfully repeating the same words, but they mean different things every time. Each use of a set phrase refers to a unique situation, with different people involved and problems to solve.

We do that with more than words. Around 600 BCE, the Etruscan people in central Italy had the custom of bundling several wooden sticks around an axe to signify honor and authority.

The Romans took up that tool, which they called fasces, and used it to remind people of the individual power and authority of a magistrate. Sometimes it was used directly for corporal punishment, but its function was mostly symbolical. After the fall of the Roman Empire, a new idea spread across Eurasia: force can snap a single rod, but not a bundle of them. Following that, kings and nations took up the fasces as a symbol not primarily of strength, but of unity and harmony. It is still in use today, with a similar meaning, in countless official symbols and images.

But when it was chosen by Benito Mussolini as the emblem of his National Fascist Party in 1926, the meaning of the fasces was another one still: not merely authority and unity, but a populist reminder of the (supposed) grand heritage of Imperial Rome. Today, most Italians regard it as a symbol of the atrocities of war, similar to how the Nazi swastika is seen all over the world.

I made this short historical detour to show how the meaning of the same icon will change as history unfolds. The events of the world add their colors to it. Each of its adopters brings in their experiences and ideals. And the very existence of that symbol in the past can alter its significance in the future. This is what Menard meant when he wrote that much has happened since the original Quixote, and "among those events, to mention but one, is the Quixote itself."

III

There are two elements in all this that seem to be at odds with each other. On the one hand, things like a proverb, a symbol, or—as in Borges' story—a novel have some sort of universality. They transcend the ages and remain applicable in different contexts. On the other hand, they acquire a unique flavor every time, dependent on the specifics of the people and times involved.

This is not a paradox, though, but a typical result of chaotic processes.

In Chaos Theory, a process or system is chaotic if even the tiniest difference in conditions will lead to very different results in a short time. Whether it's a butterfly flapping its wings or Adolf Hitler dying young in an alternate universe, the ripple effects spiral out and potentially make a huge difference.

But chaos isn't necessarily about endless novelty and disorder. Often chaotic processes lead to predictable behavior—called "attractors"—like coming to a stand-still or repeating the same events regularly. For example, a human heartbeat at rest and the Moon revolving around the Earth are pockets of regularity in a chaotic world.

And then there are "strange attractors". These are a weird mix of the complete unpredictability of chaos and the complete predictability of periodic attractors. When a process is in a strange attractor, its behavior almost repeats, nearly—but not quite—returning to the same conditions as before, except with some small differences that may or may not lead to huge changes in the near future.

This is what comes to mind when I read "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote". Every moment in time is unique in many ways, but there are parts of reality that almost repeat. Except they don't really repeat, and the small differences may lead to very different outcomes, interpretations, and meaning. History doesn't repeat itself, but it might be caught in a giant strange attractor.

I love Borges the author because he appears to have understood, at an intuitive literary level, deep truths about reality that physicists and mathematicians hadn't even discovered in his time. Chaos Theory is a rabbit hole that they're still busy exploring to this day. His intuition for the mathematical beauty of the world—in its regularity and in its chaos—transpires from his stories, and "Pierre Menard" is a prime example of that. ●

Cover image:

The Hoosier Don Quixote, Udo Keppler