Close Reading of a Modern Japanese Vignette

Things you can see by looking over a local's shoulder.

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Eutah Mizushima, Unsplash

My friend M., who is almost as forgetful as myself, accidentally bought the same self-help book twice, so I got a free copy. The book is titled 自分という壁, meaning something like The You Wall, and it was written by Gensho Taigu, an exponent of the recent charming trend of Hip Monks (for lack of a better term)—Buddhist monks with Youtube channels and the tech savvy and street smarts needed to connect with the younger generations from the austere wooden temples they live in.

The book is a modern synthesis of Buddhist philosophy, augmented with a bit of psychology and applied to the daily life of the modern Japanese. Of course it comes with a cute enlightened cat mascot ready to sooth you at every chapter heading. As far as self-help books go, it's a nice book, short and to the point, and I think many readers will find something that resonates with them between its covers (unfortunately it doesn't look like it's been translated to English yet).

But there was one passage, a little autobiographical parable, that struck me as something worth sharing on Aether Mug. I find it interesting not so much for the thing it teaches (you'll see why in a minute) but for how much it inadvertently reveals about Japanese culture. This is a book written by a Japanese for a Japanese audience, so it's a great way to see the local culture without the usual Western lens.

Here is an AI translation of the full passage, which I retouched a little:

What I Learned from a Non-Bitter Foreigner

When I was a student, I had the following experience.

One day, I got on a crowded train carrying a lot of luggage, including a large bag with my karate uniform and protective gear. I put the luggage at my feet. Naturally, other passengers gave me disapproving looks that said "You're in the way." I was aware of being a nuisance, but I had so much luggage that I thought, "Whatever, it's not like there's anything I can do about it..."

Then, at one point, a foreign man who had got on the train near me turned to me and said, "Your luggage is in the way, so please put it on the overhead rack."

I was startled to be spoken to so suddenly and was on guard for a moment. But there was no anger or bitterness at all in his manners. He just seemed to be conveying that it would be better to do that, that it would be good for both of us.

And he helped me put the heavy luggage on the overhead rack.

If someone had bluntly said to me, "You're in the way, [jerk]" or "You're so inconsiderate, [idiot]" my younger self at the time might have been irritated. But I felt a welling sense of gratitude for the foreign man who matter-of-factly pointed it out and helped me.

In this way, even if you have the same feeling, how you interact with the other person can greatly change how it comes across to them.

We Japanese tend to be relatively shy and not good at pointing these things out to others or speaking frankly. But maybe we need to learn this attitude from the foreigners who act straightforwardly without unnecessary implications.

I sometimes think I'd like to share more about my observations of Japanese culture as someone living inside it, but I always desist for fear of creating black-and-white pictures and caricatures. I'll do a (sort-of) close reading of this passage as an attempt at a middle ground: the text is original, and my comments are just my interpretation.

Let's go piece by piece.

When I was a student, I had the following experience.

The path to becoming a Buddhist monk is very similar to any other career. You take compulsory education and usually also high school, then some form of higher education, preferably one of the many Buddhist universities in Japan. Then you do a couple of years of training, and finally you're ordained. Taigu seems to be an exception, because he was ordained at 10, but he rebelled and left his temple as a teenager, and probably lived as a rather typical student in his teens.

One day, I got on a crowded train carrying a lot of luggage, including a large bag with my karate uniform and protective gear. I put the luggage at my feet.

The author is a karate practitioner. The fact that he had to ride a train to and from his dojo is normal in a Japanese city, as the vast majority of transportation is by train rather than car.

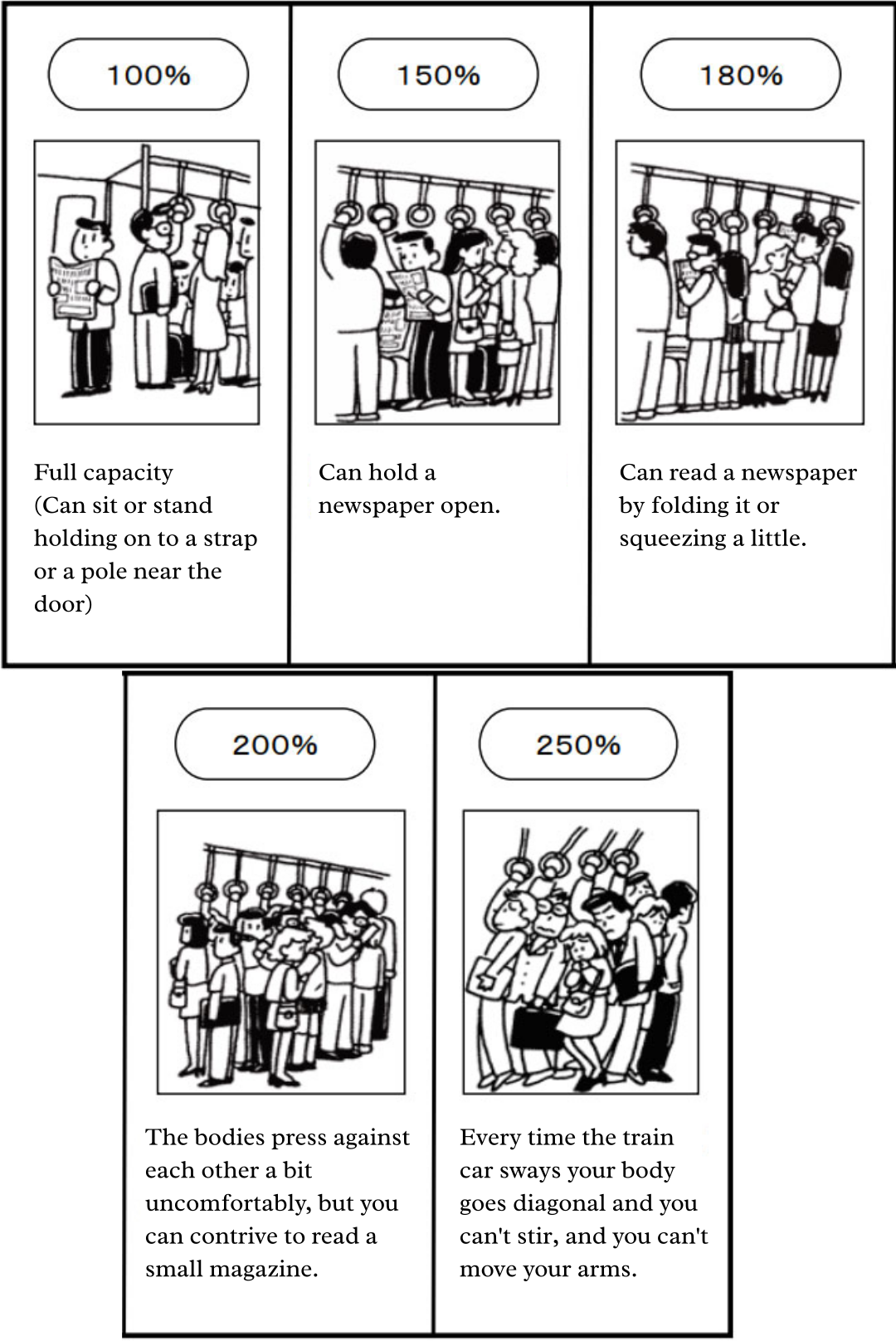

A "crowded" train in Japan can be extremely crammed, as in, I-don't-have-the-luxury-to-bend-my-arm-to-scratch-my-nose crammed. Big luggage can indeed be quite a problem, forcing people to stretch uncomfortably and lose their balance to avoid stepping on it.

Naturally, other passengers gave me disapproving looks that said "You're in the way."

Here the deeper side of Japanese culture begins to come out. People, especially in a big city like Tokyo, will rarely express their discontent directly, because doing so would attract attention to them. Exposing yourself to the eyes of the "indefinite others" (世間 seken in Japanese) is treated as a risky thing to do, because they might look down on you. The fact is self-perpetuating: since no one exposes themselves, the price of being the first one exposing yourself is highest. This makes for very peaceful train rides.

At the same time, being unable to address the problem directly will make the problem itself more irritating. The best action plan left to you is to turn the seken weapon around and make it really obvious that you're annoyed, without actually saying it. You apply pressure on the perpetrator as an anonymous member of the "indefinite others" collective. This is what the author experienced on the train.

I was aware of being a nuisance, but I had so much luggage that I thought, "Whatever, it's not like there's something I can do about it..."

There is a tinge defiance in his attitude here. He's steeling his mind against the pressure of the others, telling himself that it's not really his fault if his bags are bulky. He is in defense mode.

Then, at one point, a foreign man who had got on the train near me turned to me and said, "Your luggage is in the way, so please put it on the overhead rack."

I was startled to be spoken to so suddenly and was on guard for a moment.

This is meant to be a rather surprising turn of events, as indicated by his action-like narrative. It's startling for the average Japanese reader for two reasons.

One reason is that people don't usually talk to you out of the blue like that. Even I, born and raised in a rather talkative country, have unwittingly grown into this mindset after many years in Tokyo. Strangers talking to me on the train or on the street happens maybe once or twice in a year, and most of those times it's from non-locals. (To be fair, in Osaka and the surrounding Kansai region it's relatively more common to chat with strangers.)

The second thing that makes this passage surprising is that the person talking to him is a foreigner. Foreigners (intended as people who are not Japanese natives) are a small minority even in Tokyo, and almost none of them speak Japanese. Thus, having one of them talk to him, a Japanese person who is perhaps not very confident in their spoken English, is a very rare and possibly embarrassing situation. The fact that it happened in front of many other Japanese strangers makes it even worse.

This startled response is something I experience every now and then when I "suddenly" talk to Japanese strangers—even if I talk to them in fluent Japanese. Many expats find this reaction insulting and racist, and I see their point. There is definitely a tendency to stereotype people based on their appearance, and that's never a healthy thing to do.

Still, I don't see it now as a major social issue as it might be in other countries. Japanese culture is indeed very homogeneous, and the behavioral patterns are indeed largely correlated with the ethnic background. The "different face = different behavior" simplification does work quite well in the vast majority of cases.

Also, in most cases of discrimination I experienced directly, the discrimination was not a way to look down on me or any other kind of racial superiority statement, but mere hesitation as to how to behave and how to not look like an idiot themselves. If anything, Japanese discrimination towards me often consists in elevating me to some noble or gifted being somehow genetically out of reach of the aspirations of a Japanese native. This is bollocks, of course, and I feel uncomfortable when it happens, but it's much more innocuous than the real racism you see elsewhere.

That's not to say that there is no bad discrimination happening in Japan. I have it easy because I look Western, but things could be very different for, say, South Asian immigrants. I cannot speak for them, and I do think that the stereotyping of people should be eradicated in any case. I made this detour to clarify that the author's being startled by a foreigner talking to him doesn't necessarily mean he was a terrible xenophobe or racist: he was an average member of his culture, with the virtues and the problems that implies.

But there was no anger or bitterness at all in his manners. He just seemed to be conveying that it would be better to do that, that it would be good for both of us. ... In this way, even if you have the same feeling, how you interact with the other person can greatly change how it comes across to them.

This is the key message of Taigu's parable, and the least surprising thing for me. More interesting is the fact that he needed a foreigner to display this good example. I think it paints a different picture from the (also stereotyped) view of Japanese people as always polite, always obedient, always calm. Guess what, they're human too.

We Japanese tend to be relatively shy and not good at pointing these things out to others or speaking frankly. But maybe we need to learn this attitude from the foreigners who act straightforwardly without unnecessary implications.

This is a rather common self-stereotype held by many Japanese. I find it to be an interesting kind of "collective self-consciousness", and it goes to show the point I mentioned earlier: the discrimination here, as problematic as it might be in principle, does not have a clear "superior side", a will to oppress and marginalize a minority.

Still, it's undoubtedly a gross oversimplification. There is no Foreignland, no single country inhabited only by patient, helpful straight talkers (or whatever other trait they might have observed in a small random sample of non-Japanese people). The redeeming element is the author's softening of the statement with "tend to be relatively", which is more than most would do.

This parable works fine for most of its intended readers, and it sends a positive message using the most benign kind of stereotype. It would be unfair to judge the author harshly on this one, and that's not my goal. He is writing for people who will see nothing wrong in that worldview, and who will not be significantly nudged towards xenophobia by the text (if anything, the opposite). This is—I should repeat—a good, unpretentious self-help book.

I decided to dissect this passage to do what I would call "backgrounding".

In literary analysis, foregrounding is when an author highlights their message by presenting it in an unusual or surprising way, either in the use of language or in the way it subverts expectations of what will happen. As a reader, you intuitively focus on the unusual bits, and understand them as the most important part. I like to think about it the other way around, though: the events and descriptions that are not at the center of the narrative will tend to be the most typical and representative of what the intended readership will consider "normal". The contrast works both ways. In that sense, to a large extent, whatever is in the background will tell you more about the world than it does about the author themselves. It's a neat trick to use when learning about different cultures.

In Taigu's story, the foreground (someone asking another person to move their baggage) is something that probably would not have been foregrounded by a Western author. The background (the crowded train, the silent hating, the fact that he was startled by the foreigner), on the other hand, is rather more fascinating. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Eutah Mizushima, Unsplash