Conversational Humor Is Funny Only After You've Seen It Click

Most funny interactions betray the usual categories and seem to be evolutionary or emergent

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

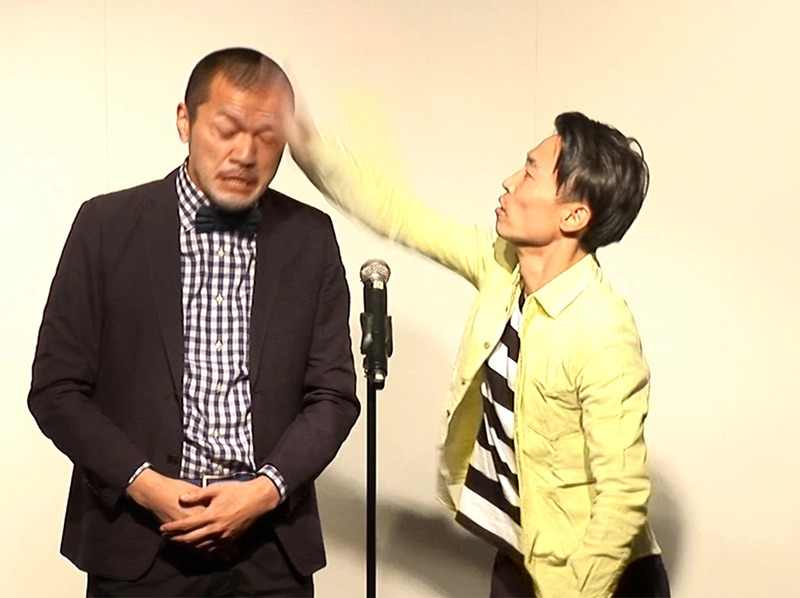

Cover image:

Two Japanese comedians (Kaminari) performing manzai

Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better but the frog dies in the process.

― E.B. White

If you want to become integrated in a different culture, the last thing you can hope to master is the local humor.

This was a surprise for me when I became proficient enough in Japanese to understand 100% of what was being spoken around me. I could understand the content of the jokes and gags popular in Japan, yet many of them simply fell flat on me. The opposite was true, too. Much of the humor that I always found to be effective in Italy would simply implode when translated to Japanese. I wondered why and, I hate to admit, I looked up the scientific literature. My verdict: the science on this seems incomplete.

Some joke researchers—all very serious frog-dissectors—separate jokes into three categories: linguistic jokes, cultural jokes, and universal jokes. Linguistic jokes are those that play with words, meanings, and sounds in the local language to humorous effect. Cultural jokes are mostly about stereotypes for nationalities, religions, and things like that (I guess that Chuck Norris-type jokes fit in this category as well). And the universal jokes are those that stand on their own legs, based only on logic (or logical contradictions) and on knowledge that everyone in the world has.

The universal and linguistic jokes were never a problem once I understood the language. If anything, I noticed that the linguistic jokes are more funny when you're not entirely fluent, maybe because they have an aura of novelty, or because they give you the satisfaction of "getting" them all on your own. Here's a cookie, me.

The cultural references took longer, but I'm more or less able to get them now, after being immersed in Japanese culture for many years. With time, the local comedians' culture-grounded jokes became gradually more intelligible and funny to me. Those compose perhaps 40% of all the humor I hear in the language.

But most cases of humor turn out not to depend on linguistic play, cultural tropes, or canned jokes at all. The straightforward understanding of their contents is all there is, which would make them fall in the "universal joke" category, except they depend completely on the social context. They're funny for some and meaningless for everyone else. There seems to be this other category that I haven't seen mentioned by any scientist. Here, I think, lies the final frontier for the language learner.

When I'm the one making jokes in Japanese, I have full control of how much cultural context I assume. Obviously, I try to stick to the self-contained type of humor, yet a lot of it is lost on the Japanese listener. The contrast is stark when I'm in a mixed-culture group. I have a Spanish friend and an Italian friend that I hang out with often, and all of us have Japanese partners. Every time, we end up with a clean split: our "Mediterranean jokes", as we've come to dub them, are normally-funny for the three Europeans, and (wearily) resisted by the Japanese.

(Fortunately, that rift has turned into its own shared running joke: we settle for bantering about which culture has no taste for what's really funny.)

I'll make a few examples. One of the first and most shocking realizations of every Western learner of Japanese is the almost complete lack of what we call "irony" in this country. Saying the opposite of what you think for laughs simply doesn't occur to most Japanese people.

If, for instance, you see a snow blizzard outside when you're about to go out, you might say "ah, so sunny, we should change into our swimsuits!" In Japan, that will often earn you a look of concern for your sanity, and a heartfelt recommendation not to do that. (The Japanese do have a form of sarcasm, called hiniku, but it is only used to mock others, and very sparingly.)

Coming from a family, on my mother's side, where irony and sarcasm are the main sport, and pushing the line between "funny" and "offensive" is a fine art (sometimes successful), sealing all of that away from my Japanese social life is a constant battle.

There is also a kind of humor where you say something nonsense, impossible, or utterly exaggerated instead of the real thing. It's similar to irony, but it requires the other to play along to make it worthwhile. My Italian friend gave me a good example this very morning. He'd gone on a short walk with a friend and got back home only twenty minutes later; when his Japanese partner (also my good friend) asked him where they'd been, he replied that they'd made it almost to the border with Ibaraki, a neighboring prefecture.

Now, given that Ibaraki is some 44 kilometers away from their house in central Tokyo, I or another of our Western friends would have promptly responded "oh, were the corn fields in bloom over there?" or "man, your feet must be hurting bad right now!", or something along those lines. My friend's partner, on the other hand, was confused: how was it even possible for them to walk that much in twenty minutes?

At this point I should make it clear that my friend's partner, and all the other Japanese that I describe not getting jokes, are highly intelligent, reasonable, and funny people. On top of that we (the blundering Western jokers) have swallowed our pride and explained our humor to them inside out more than once. They "get" what we're trying to do—they just tend to reject the premise. Attempting such rhetorical devices feels so pointless and unfunny to them, that they forget their existence and end up being caught off guard the next time it comes up. Even when they later get the speaker's intention, it's too late to fix the humor. The joke has fallen flat, and its pointlessness seems plainer than ever. A perfect vicious cycle.

On the reverse side, I was initially baffled by the classical manzai genre of Japanese comedy. It requires two people to assume complementary roles: the boke (idiot) says something ludicrous or silly, and the tsukkomi (dunker, shover) loudly and often violently calls them out for their silliness. The two comedians repeat this sequence over and over throughout each skit. Manzai dominates the vast majority of Japanese comedy, and it's been repeated in infinite variations for decades. It's the kind of thing that never goes out of fashion.

In my early days of learning the language, I didn't get why doing that same stunt again and again could be funny to anyone. Was it a form of sadism, watching the tsukkomi slap the boke behind the head every ten seconds for two minutes? But I kept watching them for the pleasure of seeing my language comprehension improve, and over time I started to get it. It wasn't the content of what they said (although the good ones do say interesting things), nor was it the physical attacks themselves, but the tension in the small gap between error and correction, the rising expectation of exactly when and how the tsukkomi comedian will be forced to react to the current joke.

And it's not something specific about Japan, or about very different cultures, either. I used to be mildly annoyed by a French friend of mine—i.e. culturally quite close to me, an Italian—who never misses an opportunity to make dirty double entendre jokes. You know, stuff like, "hey, she said she loves the color of 'Uranus', wink wink". Rather condescendingly, I believed his sense of humor was stuck at adolescent levels... until I learned that double entendres is a well-known staple of (grown-up) French humor. (In retrospect, I should have guessed from the name of the joke category.)

More surprising still for me was seeing that even my friend from northern Italy, a compatriot, simply doesn't get the kind of teasing/bantering that I took for granted and always loved during my whole life in central Italy. It didn't register as humor for him, and I ended up upsetting him more than once because of that. After I explained to him that my obviously exaggerated remarks were meant to be the start of a funny back-and-forth with him, he tactfully asked me to never do that again.

All of this leads me to a hypothesis: what makes most types of humor hilarious is not their content in itself, nor the cultural references, but seeing others laugh at it. Even when you ensure that the receiver has fully understood the context and language involved, the difference between laughter and a blank stare hangs on whether they have seen the humor actually cracking someone up or not.

All humor is an emergent phenomenon. It's not decomposable into an inventory of "funny bits and bolts", each hiding in it a portion of the overall comicality. And this specific kind that I'm talking about is its own self-fulfilling prophecy: observing others doing it well is the required catalyst you must include to do it well in turn. You can't create it unless you believe you'll enjoy it, and you can't believe such a thing until you've somehow verified that it is enjoyable. It's a catch-22 that only dissolves when others perform the humor in front of you.

I've seen this with the Japanese manzai skits: they became funny after I watched my wife laughing to tears to them. I also catch our Japanese friends laughing furtively at our "Mediterranean jokes", too (although they are quick to recover their unimpressed attitude). We could call this strange category acquired humor.

This hypothesis gives us a turtles-all-the-way-down problem, though. If everyone needs to see a humor sample fully formed and performed before picking it up and spreading it to others, where did it come from in the first place? It can't be an infinite regression! (I don't think it likely that the first living microorganism just happened to be a very funny fellow; not before dividing a few times, at least).

The answer can only be serendipity, the sudden appearance of hilarity that surprises even the people who produced it. A "random mutation" in the way we interact, a lucky convergence of all the right elements, crucially including the good mood and readiness of those involved to laugh at something new. When that happens, the originators of the new format observe themselves laugh about it—without initially understanding why—and can start believing in it. They plant a seed for a new strain of humor to spread.

Having an origin in happenstance doesn't mean that it's all about luck, though. Just as you can hope to eventually score a point if you kick the ball towards the goal a sufficient number of times, you can "willfully" stumble on usable new humor by sheer perseverance.

This brings me to propose three rules you'll need to follow if you want to sow the seeds that will populate the future joke-space:

- Be playful and creative in the way you communicate with others, introducing surprising, whimsical, and unexpected patterns and points of view.

- Be very patient with the strange quirky behaviors of those around you. Most new patterns will not be funny.

- Be ready at all times to see the humorous in everything around you; if unsure how to react, laugh. You might just start something new.

On the moral need to go through all that just to increase the catalog of workable joke types, I won't comment. Either way, I think we should do those things. To me, those three rules sound like a good way to enjoy life regardless of how much you care for the variety of humor out there. Maybe joke variety is, after all, one measure of a community's ability to be happy. ●

Cover image:

Two Japanese comedians (Kaminari) performing manzai