Hi No Youjin

On quaint devices for time-travel

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Jacob Gonzales, Unsplash

Touch Stone, Touch Wood

One of the luxuries of living in Rome is getting to visit incredibly ancient ruins any time you want. There are literally too many of them (public infrastructure works need to stop for months whenever they accidentally dig up an imperial-era domus or an Ionic capital, so they feel more like journeys through a minefield than construction projects). It is a luxury that, in retrospect, I didn't take advantage of enough during the many years I lived in the Eternal City (when I tell people in Japan that "I'm from Rome," some react as if I'd told them my uncle is Julius Caesar.).

That's not to say that I didn't appreciate the city's treasures, though. Simply standing in front of one of those sun-washed marble or brick walls, touching them, feeling them loom over me, is never not awesome in the literal sense. While I'm there, all the modern technology and cultural paraphernalia around me fade away from my consciousness. I no longer see or hear the cars and sneaker-wearing people around me, because I'm transported three quarters of a million days into the past, when those stones were cut and set down so heavily as to stay there forever.

I can't see ancient Rome in my mind, but I can feel this strange connection to the anonymous human beings who stood, two millennia ago or more, in that very same spot, touched with fingers just like mine the same rough patch in the stone, experienced the same palette of emotions, instincts, and weaknesses as I do. I feel the urge to observe them, to ask them questions. Time itself seems to stop mattering. A lifespan seems briefer than a spark.

For many years, I thought these time-traveling powers were essentially a property of rocks—one of the most durable substances we encounter in daily life. Stone and metals carry eternity inside them, I thought. Temples and walls, being stone shaped by human hands, simply make that eternity more palpable to other humans. What I felt was perhaps a mineral view of the world. I now see that I was wrong.

After moving to Japan, I learned that the same epochal awe—the same sense of dissolving time and cross-generational connection—can be evoked even by a building containing no stone at all. Douglas Adams explained why:

I remembered once, in Japan, having been to see the Gold Pavilion Temple in Kyoto and being mildly surprised at quite how well it had weathered the passage of time since it was first built in the fourteenth century. I was told it hadn’t weathered well at all, and had in fact been burnt to the ground twice in this century. “So it isn’t the original building?” I had asked my Japanese guide.

“But yes, of course it is,” he insisted, rather surprised at my question.

“But it’s burnt down?”

“Yes.”

“Twice.”

“Many times.”

“And rebuilt.”

“Of course. It is an important and historic building.”

“With completely new materials.”

“But of course. It was burnt down.”

“So how can it be the same building?”

“It is always the same building.”

I had to admit to myself that this was in fact a perfectly rational point of view, it merely started from an unexpected premise. The idea of the building, the intention of it, its design, are all immutable and are the essence of the building. The intention of the original builders is what survives. The wood of which the design is constructed decays and is replaced when necessary. To be overly concerned with the original materials, which are merely sentimental souvenirs of the past, is to fail to see the living building itself.

— Douglas Adams, Last Chance to See

Most important buildings in Japan's history up to the 19th century were built in wood, so they naturally rot and deteriorate over time. Devastating fires and earthquakes were frequent, and many important landmarks were destroyed and rebuilt several times over.

When building the Golden Pavilion or Ryoan-ji, no one expected them to last forever. I suspect, like Douglas Adams, that wasn't the point at all. It's no coincidence that some of the oldest companies in the world are Japanese temple carpenters.

There are many carpenters even today specialized in all the ancient techniques necessary to build Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines.

So immutable rock is not essential to the time-traveling effects I found in Roman monuments. What, then, is the key ingredient?

It's not just physical age, either—the materials don't need to be that old at all. A modern residential building completed in 2013 doesn't incite the same sense of wonder in me as the Ise Grand Shrine, even though the shrine was last rebuilt in the same year (they've been doing it all over again every 20 years since 692).

What I discovered is that something doesn't even have to be a building to work its magic on me. I learned this only a few years ago, from the comfort of my own living room.

Intangible Paths

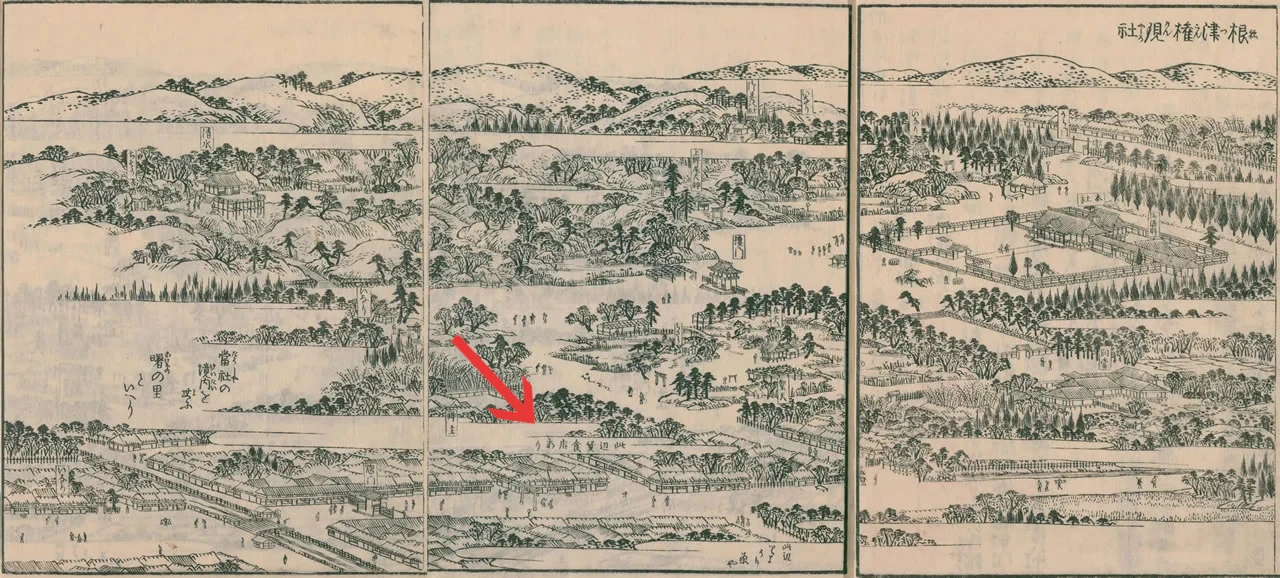

At the time, I lived in Nezu, an old Tokyo neighborhood a stone's throw from the famous Ueno Park. The whole area was once part of Edo's shitamachi, or "low town," where commoners—merchants, artisans, and craftspeople—lived and worked. Of course it has undergone much transformation over the years, but its sleepy side alleys and hidden temples retain a vintage charm that you can't find in many other parts of modern Tokyo.

On winter evenings in Nezu, when darkness had just reached its fullness, I would sometimes hear a peculiar sound and a voice coming from the back street outside my window.

The sound was that of a hyoushigi, a traditional instrument consisting of a pair of hardwood or bamboo sticks that are banged together to produce a pleasant, high-pitched wooden click. It's often used in traditional Japanese arts, like sumo matches and theater performances, but what I heard in Nezu was nothing of the sort. From the street came two clicks, followed by an old man's voice chanting hi no youjin! (火の用心), which means "be careful with fire!"

The routine was repeated once every twenty or thirty seconds. It felt too peaceful, too ritualistic to be someone scolding a child or sounding an alarm. I didn't know exactly what it was, but the whole thing felt wonderfully quaint.

When I looked it up, I learned that it was a "fire watch patrol"—volunteers walking around the neighborhood to remind all inhabitants never to forget the dangers of fire. Even today, most buildings in the area are made of wood, and a single spark could mean destruction for hundreds of households. To my delight, I also read that this practice hasn't changed since at least the year Keian 1 (1648), when a directive from the town authorities of Edo containing the exact term hi no youjin ordered:

町中の者は交代で夜番すべし。月行事はときどき夜番を見回るべし。店子たちは各々火の用心を厳重にすべし。

People in the town should take turns doing night watch. Monthly officials should occasionally inspect the night watch. Tenants should each be strictly careful about fire prevention (hi no youjin).

There it was again, that feeling! Now, every time I heard the old patrolling man's voice intoning his hi no youjin in the night, I had to stop whatever I was doing and just listen. I was again transported to that place outside time. I had no trouble at all imagining the same exact voice echoing through that same street four hundred years ago, when everyone went around in straw sandals carrying paper lanterns in the night. They were there now, right outside my house!

And so I never once looked out the window to see the source of that voice. I just listened as it repeated its incantation at slow, regular intervals, crisp in the dead silence of Japanese neighborhoods. Faint at first, then louder, then fainter again, and then it was gone. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Jacob Gonzales, Unsplash