Human Stigmergy

The world is my task list

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

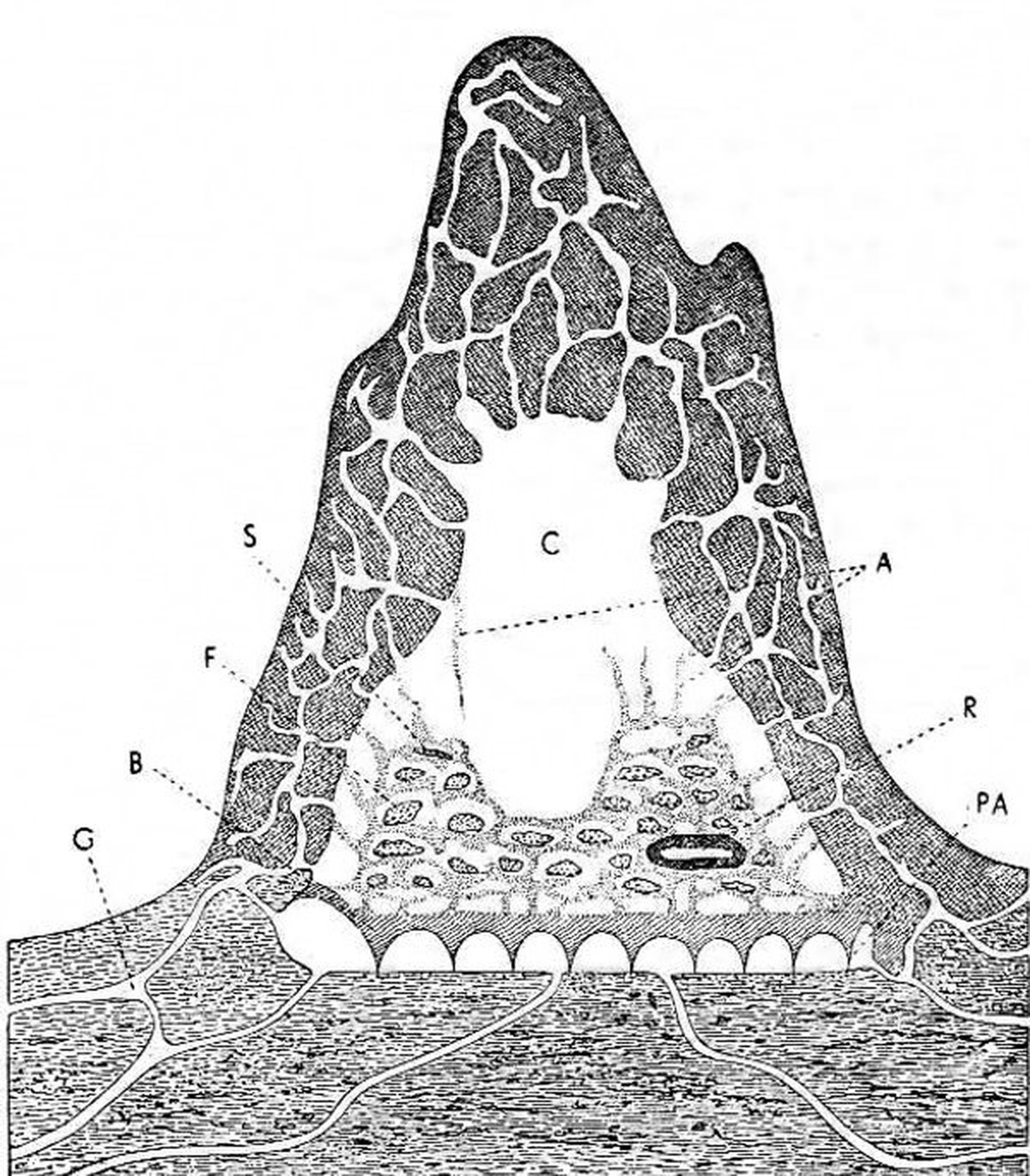

Cover image:

Termite mound cross-section, Wikimedia Commons

Termites and ants have no central planning. There are no architect ants in a nest-building project, no sponsors or supervisors, no instructions. Each worker is unaware and completely uninterested in what form the final mega-structure will take. No blueprints are to be found in any of their minds or outside them. Yet they build them all the time, and very well, too.

Their substitute for plans and blueprints is what biologists call stigmergy. Each worker instinctively marks the environment with pheromones as it works—the termite infuses it in the dollops of mud it deposits, the ant marks the path it took to find food—then other workers smell the pheromone and act based on it. This is repeated by each insect, and it is all they need to build and stock their great cathedrals, complete with effective ventilation shafts, highways leading straight to the best sources of food, and everything else they need to thrive.

This topic never ceases to fascinate me. It's a demonstration that great things can be achieved together in a fully decentralized way. Intelligence can be distributed rather than fenced off. The exercise of power isn't the only way.

But stigmergy interests me in yet another way—a more mundane and pragmatic way: it is proof that there are other kinds of memory besides the "mental".

I have a terrible memory, and I forget the concrete and ephemeral duties and to-dos of my daily life all the time. I've learned to trust my ability to remember to do things exactly 0%. I live on the solid certainty that I will forget things. To-do apps and notes help, but they're never enough. Digital supports have the fatal flaw of requiring me to remember to check my digital devices—something I do often, but not necessarily when I need it.

A single termite isn't very smart. I doubt it even knows what it is doing while carrying its ball-shaped bricks up its half-constructed mound. I'm grateful to it for just how low it sets the bar for me. Can memory-less Marco learn something from that termite? I can't secrete pungent pheromones (not intentionally, at least), and that's probably a good thing. But I have two very useful appendages with many accurate fingers working for me, and those should function as good substitutes.

Eusocial insects shape the environment around them as a form of external, localized memory. I do the same! If I decide I want to refill my bicycle's tires with air the next time I go out, I don't even try to commit that to memory, nor do I write a memo on Google Keep: I immediately take the floor pump and place it on the path out of my room. When I need to remember to throw trash away, my wife or I put the bags right at the foot of the front door. To keep track of how many hours I've worked in a day, I move Lego bricks from one side of my computer's monitor to the other at every periodic break.

All these acts remove the need for me to remember, even to know. I could hit my head and have my short-term memory wiped clean, and simply looking at the pump, the garbage bag, the toy brick would instantly inform me of what I'm supposed to do.

It's not just me. People seem to do this all the time without much thought: they leave their umbrellas in the foyer right next to their shoes, to remember to check the weather; they drape their jackets over the backs of their seats in cafes, both to find the seats again and to signal to others to look elsewhere; they tie knots in strings to keep track of their lives.

This is fabulous. We tend to think of memory and mind-related concepts as purely abstract, separate, and invisible processes that happen somewhere up there—at best in the brain, at worst in a separate "world of the mind" à la Descartes, entirely disconnected from the "physical world".

Humble ants teach us otherwise. ●

Cover image:

Termite mound cross-section, Wikimedia Commons