In Japanese You Need a Dictionary to Count Things

On Josuushi and questionable language approaches

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Katsushika Hokusai, Hokusai Manga

This isn't a blog about Japanese, but there are some aspects of that language that are just too interesting keep to myself. Here I want to share another one of those, one that might lead you to question the sanity of those who willfully speak it. Insane we are not, though, as I hope I'll convince you by the end.

A Wake Up Call

One of the first things you learn of a language is counting to ten. When you're getting started, Japanese counting seems to be as easy as any other language: one is ichi, two is ni, three is san, and so on. These words come from ancient Chinese. (If you remember only one of these, remember 2=ni, because I'll use it in the examples that follow).

The numbers from eleven up are extremely regular combinations of the first ten. For example, thirteen is just juu-san, literally "ten-three". "No big deal!" you think as an endearing beginner, "I've got this!".

Then you learn a bit more. And more. And more.

Let's put aside the pronunciation quirks, which aren't all that special compared to any other language. In what follows I'll focus on the numbers and the grammar.

First of all, there is a second, entirely different way to count to ten. Let's call it the "traditional" way, because it is based not on imported sounds but on the local words that predated Chinese influence.

| Digit (Kanji) | Japanese (modern) | Japanese (trad.) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (一) | ichi | hi |

| 2 (二) | ni | fu |

| 3 (三) | san | mi |

| 4 (四) | shi | yo |

| 5 (五) | go | i |

| 6 (六) | roku | mu |

| 7 (七) | shichi | nana |

| 8 (八) | hachi | ya |

| 9 (九) | kyuu/ku | ko |

| 10 (十) | juu | to |

This still sounds very manageable: you'll just learn twenty words instead of ten, and when to use which.

But if, at this stage, you get the bold idea of applying your new knowledge to a basic sentence like "I bought two books", someone will politely tell you that you're doing it wrong (or, more likely, they'll think so without telling you, out of extra politeness).

You can't just put the number next to the noun it's meant to count, as you do in English. You need to qualify the number based on the kind of thing being counted!

Some Complications

It turns out that, on their own, those beginner-friendly words you learned above are only good to communicate abstract numbers, like "the number 2" or a rocket launch countdown. When you want to refer to numbers of things—arguably the most common use case—you need to attach something called josuushi, or "counter word", after the number.

For example, to count books, you have to add the kanji 冊 satsu after the number, so that the "two" part of "two books" becomes "ni-satsu" instead of just "ni". Satsu is a word specialized for counting books, and nothing other than books. To say "two magazines" the number part will become "ni-bu", and for "two carrots", "ni-hon".

In total, there are around 500 different josuushi in the Japanese language. Other common josuushi are 人 nin for people, 匹 hiki for animals roughly smaller than people, 頭 tou for animals roughly larger than people, 羽 wa for birds, 本 hon for long objects, 枚 mai for flat and thin objects, and 個 ko for smallish objects that aren't too long or too flat.

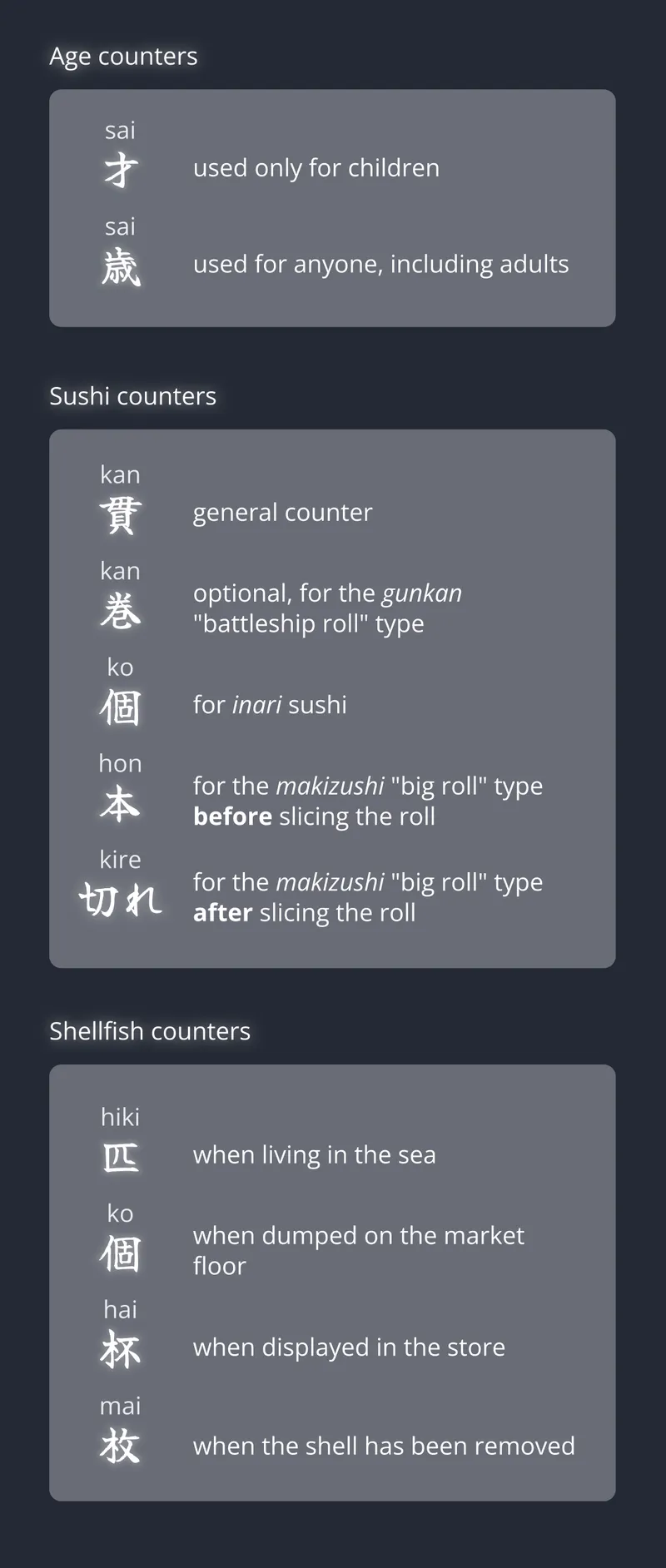

As you might have already surmised, it's not always crystal clear which counter word you're supposed to use. There are detailed rules for the right counters for the right situations, sometimes even dictating which kanji to use in writing even when the spoken pronunciation would be the same.

There are also many irregular cases, of course. For whatever reason, you're supposed to count butterflies with 頭 tou, the counter usually reserved for big animals like cows and elephants; sometimes 貫 kan is used to mean a pair of sushi, instead of one; the same 帖 jou counter represents groups of 10 when counting paper-like nori seaweed, 100 when counting tissue paper, 20 when counting small-sized washi rice-paper sheets, and 48 for Mino washi, a kind of paper traditional of Gifu prefecture.

My favorite bonkers counter might be that for rabbits. Being small animals, you'd expect to count them with 匹 hiki, like cats, dogs, and raccoons. Instead, rabbits get 羽 wa, the bird counter (the kanji 羽 literally means "feather"). There are many wild theories for why bunnies ended up in the same bucket as pigeons. I'll let you form your own.

Admittedly a Mess

If all that sounds like a mess to you, most Japanese speakers would agree. As Fujisawa Kazuhito (or Kazunari, kanji are ambiguous), a researcher of the Japanese language put it:

I think that almost no one can correctly use josuushi. I doubt that anyone except a fish nerd would know to count fish as ichi-bi, ni-bi, etc.

— Nihongo no Chikara, Fujisawa's blog, translation mine

People have a few ways to simplify things when necessary. For objects and abstract concepts, you can often fall back to a generic counter つ tsu. This is very convenient, but it only works up to 10 things, and can't be used for animals or people (that would be rude!). The counter for small round things, 個 ko, can also serve as a generic/abstractish replacement for lots of inanimate things, and has no upper limit.

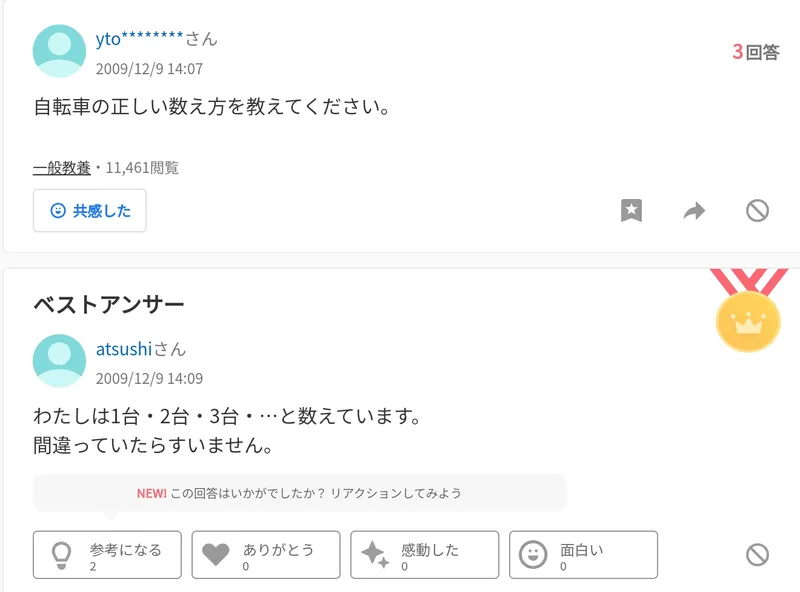

So, if you don't remember that sushi is counted with 貫 kan, you can still ask your sushi chef to squeeze you two more using つ tsu or 個 ko. They'll get it, no disconcerted looks. But using these shortcuts makes an already vague language even vaguer, and advertises to everyone around that you've given up, that you don't know how to properly count this one. That's why the internet is full of "counting dictionaries" and SEO-boosted blog posts explaining at length how to count trees, streets, and pokemon.

Doubts of Insanity

For someone not familiar with Japanese, Chinese, or other languages that depend on vast amounts of counter words, all this might sound like a terribly backwards way of counting.

(My gut response to that is that the vowel pronunciation rules in English are hardly more sensible, but I won't rub it in.)

Most languages, including English, do have the same kind of counter as Japanese, only for certain words: you don't say "three water", but "three drops of water" or "three milliliters of water"or "three glasses of water".

In these languages the counters are needed only for a category of nouns called "mass nouns", indicating things that cannot be directly counted. They don't function exactly the same, because josuushi are grammatical particles rather than nouns, but they are the closest equivalent. The main difference is that Japanese and similar languages use them for everything.

Japanese grammar has no distinction for singular and plural. The sentence 葉っぱが落ちた happa ga ochita, by itself, could mean "the leaf fell down" or "the leaves fell down". Neither the noun nor the verb carries any information about the number of things being talked about.

In other words, all Japanese nouns are mass nouns. There is no built-in counting.

(Nerd detour: This isn't entirely true. There are certain cases in which a Japanese sentence can make the singular/plural difference evident without the use of counters or grammatical elements. The secret is in the word order. Compare the familiar Japanese ambiguity of

りんごの一部が腐っている ringo no ichibu ga kusatteiru

which could mean either "some of the apples have gone bad" or "part of the apple has gone bad", with

一部のりんごが腐っている ichibu no ringo ga kusatteiru

which can only be plural, i.e. "some of the apples have gone bad". This is a subtle and very limited effect and I had never noticed the distinction consciously before researching this blog post.)

In Japanese, sometimes the singular/plural distinction isn't important, and sometimes it is clear enough from the context. But often you'll want to make the plurality of a noun evident in the same sentence, in which case you're usually forced to add the number explicitly. And if you really need to have the number, you might as well enrich it with information about the type of thing being counted.

In summary, Chinese, Japanese, and company have "evolved" to solve the same problem as the other languages—making it clear how many things we're talking about—with very different grammatical devices. This is not a standalone feature: it emerged in symbiosis with other characteristics, such as the lack of grammatical inflection and the high contextuality. And it does the job, considering that over a billion people use this approach every day.

Still, you might ask why these languages evolved into a practice that sounds more inconvenient. Wouldn't it be more efficient to embed the plurality in the nouns themselves?

Language, Evolution, and Games

Again, I could turn that question around. A German speaker might ask why English didn't evolve to distinguish female, male, and neuter grammatical gender—a practice that would surely enrich the language. And a Portuguese or Italian speaker might want to know why English and French don't allow you to omit the subject from a sentence, even when the same information is conveyed anyway by the verb inflection.

But a more honest answer is that I don't know and, as far as I can tell from my research, no one else knows with confidence.

The most reasonable explanation for these obtuse-sounding language quirks—from Japanese written/spoken dissociation and counter words to English irregular-is-the-new-regular pronunciations—may be the same that explains zebra stripes and platypus electrolocation: happenstance, drift, and exaptations. It's not a logical process, but it is a pragmatic one.

Once an approach to a linguistic function has taken hold, it might be very difficult to change it—even when it is objectively less efficient than alternative approaches.

For example, assuming for a minute that the Japanese wanted to stop using their countless kanji for writing, that would still be a very difficult task. Without kanji, the written language would be very hard to read because of the large number of same-sounding words, so they would probably need to create a huge amount of new words that are pronounced differently to remove the ambiguity. You can't change one part of the language without also changing most of the rest. (Of course, no one wants the kanji to go away, least of all me.)

Another thing to consider is the role of game-theoretical dynamics. Here I'm in the realm of speculation, because the evolutionary dynamics of language change are a new area of research. Still, it looks like a promising approach. Evolutionary game theory considers the interactions between groups of individuals. One of its main results is that the "ideal" adaptation or solution to a problem depends not only on the individual and its environment, but also—and sometimes especially—on what everyone else is doing at the moment.

For example, many social animals like meerkats and bonobos display altruistic behavior like giving warning calls to their peers when they spot danger and sharing the food they find. For any one of them, being selfish might be the more clever option in the short term: they could hide sooner, expose themselves less, and eat all the food they find. But any individual animal who went rogue like that would lose reputation within the group, and might stop receiving the same benefits from the others. They would be disadvantaged compared to the mutually-altruistic members. Being selfish might be the best strategy only if all the members of the group became selfish at the same time.

Altruism here is what is called an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS): not necessarily always better in absolute terms, but good enough that it's very difficult for any alternative strategy to replace it.

Something similar might be preventing languages from changing in certain ways. In the case of Japanese josuushi, if everyone somehow stopped using them at once in favor of another grammatical method of achieving the same function, it might work just fine. But if a small minority of rebels decided to stop using josuushi, they would have a very hard time spreading that practice to the whole population.The josuushi-denier's lives would actually get harder: they'd be left behind in certain conversations where the counter words are the only thing that disambiguates between objects, and the others would have trouble understanding what the rebels are saying.

Of course, neologisms make their way into dictionaries and populations all the time, but new grammatical changes seem harder to scale. They would have to be much more useful than the status quo in order to overcome all the friction.

But enough with the conjectures. Speaking of neologisms, Japan crucially has them for counter words, too. For instance, several foreign words have been subsumed as counters in the past few decades: to count workout sets, the counter is セット setto (set), while for packaged goods you use パック pakku (pack). Examples of indigenous neo-counters are 車線 shasen, which literally means "car lane" and is used to count car lanes, and 面 men to count sports courts.

If josuushi were really more burdensome than they are useful, people would just use the generic fallback counters like tsu and ko for all new noun categories. But they don't. This, I think, evidence enough that josuushi are actually fine, and that people love them and need them. ●

Cover image:

Katsushika Hokusai, Hokusai Manga