Meditations on the Color of Pee

The synthetic origins of what we consider normal

Anthropic Claude (Writing), Marco Giancotti (Thinking, Editing),

Anthropic Claude (Writing), Marco Giancotti (Thinking, Editing),

Cover image:

Man with Urine Bottle in his Hand, Antonio Zanchi

You've probably heard the recommendation to drink around 2 liters of water daily. A few years ago, I decided to take this advice seriously. I started carrying a water bottle everywhere, setting reminders, the whole performance. And after a couple of weeks of this new hydration ritual, I noticed something peculiar: my urine had become almost clear, barely a hint of yellow.

This observation stuck with me for reasons I couldn't immediately articulate. It was one of those seemingly trivial things that nonetheless gnaws at the edges of your consciousness.

The Evolutionary Puzzle

Here's where my brain went with this: if humans are "supposed" to drink that much water (according to modern health wisdom), then our hunter-gatherer ancestors—who presumably lived in optimal conditions they were perfectly adapted to—must have produced nearly clear urine most of the time. Yet, whenever urine makes an appearance in popular culture—movies, TV shows, even medical diagrams—it's depicted as distinctly yellow, often a deep amber shade.

So are we collectively treating something unhealthy as the baseline? Have we normalized mild dehydration to the point where we think deep yellow is the default setting for human pee? Or have we synthetically constructed an idea of "normal" that doesn't reflect biological reality?

I found this oddly fascinating. It's like discovering that you've been holding your pencil "wrong" your entire life, but so has everyone else.

Reality Checks and Nuances

Of course, my initial thoughts needed some correction (they usually do):

First off, "optimal" hydration isn't a binary state but exists on a gradated spectrum. Rather than a single perfect amount of water, there's a range where our bodies function well, with diminishing returns as we approach either extreme. Those "8 glasses" or "2 liters" recommendations represent a reasonable target within this range, not a precise threshold between "hydrated" and "dehydrated." Small deviations from this ideal aren't catastrophic—they're just progressively less optimal for long-term functioning. And this optimal range itself shifts based on numerous factors: the climate you're in, what you're eating, how active you are, your body size, and probably your genetic makeup too.

Second, is it really true that deep yellow urine is universally considered "normal"? Its portrayal in media might be purely practical—yellow is simply more visually recognizable as urine than a clear liquid would be. (Imagine a movie scene where someone holds up a clear specimen cup: "Is that water or...?")

Third (and perhaps most importantly), I was falling into what philosophers call the naturalistic fallacy—the idea that there exists some ideal natural environment that humans are perfectly adapted to. Evolution doesn't work toward perfection; it works toward "good enough to not die before reproducing."

From an evolutionary perspective, there might even be advantages to tolerating mild dehydration. Our ancestors faced constant trade-offs: spending time searching for water meant less time gathering food or building shelter. The ability to function while slightly under-watered could have been genuinely adaptive in certain environments.

Think about it—if our bodies required absolutely optimal hydration all the time, we'd be spectacularly fragile creatures.

From Observation to Insight

My innocent glance into the toilet bowl somehow spiraled into a philosophical reimagining of "normal" hydration throughout human history. Funny how one minute you're judging your own bodily fluids, and the next you're deconstructing the flawed reasoning of "crystal clear equals well-watered, therefore our ancestors must have peed like mountain springs." A little nuance can really flush away our most golden assumptions.

While there are practical reasons for media's deep yellow portrayal of urine (as mentioned earlier—it's visually recognizable), this consistent imagery might still subtly influence our perception. We might unconsciously accept amber as the default when, biologically speaking, that's not necessarily the case. It's a perfect example of how our sense of "normal" can be constructed through artificial means.

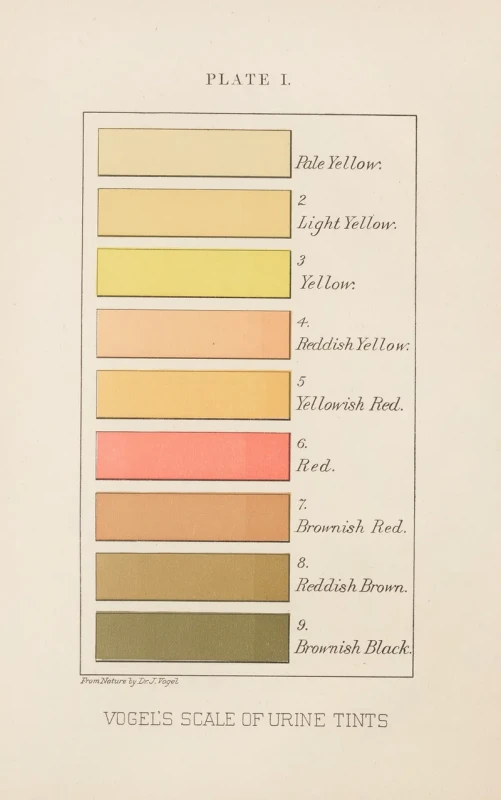

Medical professionals generally agree that pale yellow urine—not completely clear and not amber—indicates proper hydration for most people. This light straw color suggests your kidneys aren't working overtime to conserve water, but you're also not overwhelming your system.

Perhaps the most interesting lesson here is how easily we can misinterpret biological signals through cultural lenses. And that's something worth meditating on, regardless of the color of your pee. What other "normal" things in our lives might actually be synthetic constructs rather than natural baselines? ●

Cover image:

Man with Urine Bottle in his Hand, Antonio Zanchi