New Aphantasia Article on Nautilus

Rotating things without seeing the things

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

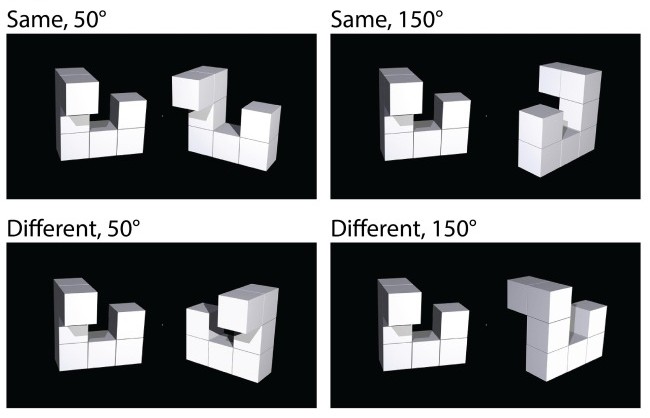

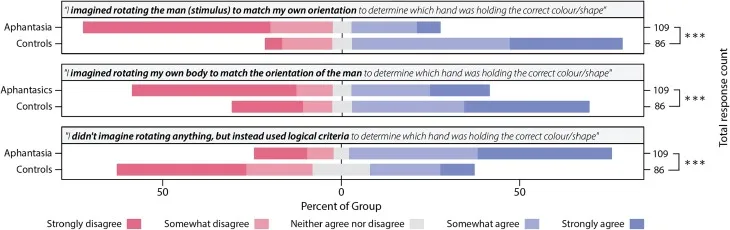

From Kay, L., Keogh, R., & Pearson, J. Slower but more accurate mental rotation performance in aphantasia linked to differences in cognitive strategies. Consciousness and Cognition (2024).

Today Nautilus published a new article I wrote about aphantasia, following my previous feature piece for them on the same subject (note: they are both paywalled). This time the focus is not on my own experience as an aphantasic, but on a recently published paper where aphantasia helped shed light on some puzzling mechanisms of the brain—and cast some new shadows in the process.

I think this result is a great example of the new territories that aphantasia is opening up for neuroscientists. I won't go to into the details here, but the paper highlights a striking finding: people with aphantasia are able to do three-dimensional manipulations in their heads better than people who can form mental images.

Considering that until now researchers believed mental imagery to be indispensable for this kind of spatial reasoning, I think that the paper will spark some interesting new research.

The paper, like my own article, is geared at the general population, because its implications are universal. But, needless to say, it has a special significance for anyone with aphantasia. There is a tendency by some people in online communities to take their aphantasia as a handicap, a guarantee that they're shut out of many essential experiences. I think that this paper deals a hard blow to that pessimistic worldview. Not only it demonstrates that aphantasics can actually be better at certain visual tasks than the visualizers—it suggests a clear, convincing reason why that's the case: many problems, including but not limited to those of spatial manipulation, can be tackled with different strategies, and not all those strategies rely on the ability to picture something.

The experiments were conducted by Lachlan Kay, Rebecca Keogh, and Joel Pearson of the University of New South Wales, Australia (the first two of which I had the pleasure to interview). Pearson is leading what is, in my opinion, some of the most important and striking research in mental imagery. For instance, in 2021 the same three authors (plus Thomas Andrillon) were the first to demonstrate objective, almost-impossible-to-fake ways to detect aphantasia, destroying the arguments of certain individuals who refused to believe subjective reports. I'm always waiting with anticipation for new papers by the UNSW group.

Unfortunately, due to space constraints on my Nautilus piece, I couldn't expand on another interesting result of the same paper. Very much in passing, Kay et al. mention that "those with aphantasia significantly favoured using analytic strategies", where by "analytic strategy" they mean ways to answer the rotation tasks using logic instead of actual mental rotations. Note how they didn't find that all aphantasics used the analytic strategy: only a significant majority did.

The obvious question is, what were the aphantasics who didn't use the analytic strategy doing?

Apparently, some 30 or 40% of the aphantasics said that their strategy was to actually rotate things around mentally—while having no mental images to rotate! What's going on here?

The authors told me that they didn't have enough data on this side of the experiment to make bold statements about it—more research will be needed to figure this one out.

I was lucky enough to catch Alfredo Spagna of Columbia University while he was visiting Japan for a conference. He is well known in the field of attention and mental imagery, and was the perfect person to bring some clarity in my confused mind. (I was unable to incorporate his comments directly in my article this time, but the insights he gave me were very useful to orient myself in this vast topic, and his explanations will definitely make it into my future work.)

I met with Alfredo in beautiful cafe in Ueno Park, and I asked him about these and other topics. He explained very kindly and clearly to me a great deal of what we know about the interplay between these various functions of the brain, and just how much we still don't understand. The mechanisms for mental rotation still largely fall in the latter category. There are theories and tantalizing hints, but no clear picture has emerged yet. Perhaps paradoxically, aphantasia might be the solution to that. ●

Cover image:

From Kay, L., Keogh, R., & Pearson, J. Slower but more accurate mental rotation performance in aphantasia linked to differences in cognitive strategies. Consciousness and Cognition (2024).