Normality and Surprise in an Image-Free Mind

On discovering aphantasia and talking about it

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

An original theory or new hypothesis of the universe, Plate XIII, Thomas Wright

Retelling What It's Like Inside the Dome

I've always found the ending of the 1998 motion picture The Truman Show to be wonderful in the literal sense of the word: it leads to some deep and interesting questions. Only much later did I realize that some of those doubts applied to my own life.

The thirty-year old protagonist of the film, Truman Burbank, has lived his whole life unaware that he is the star of a lifelong reality TV show. But one of the strengths of this story is its ending (spoiler alert): he eventually manages to get out of the dome and into the real world, although we are not shown what happens afterwards.

How will the outside world appear to his naive eyes? Will he be able to build a new, happy life out there, after all that's happened? And will he ever be able to convey what this transition felt like to anyone else?

That last question is the most familiar to me as I write this. I suspect that Truman, after a period of adjustment to the real world, might write a book titled "I am Truman", or "My Life, My Lie", or something more clever than that. The stories he can tell in that book wouldn't be that interesting in themselves, because everybody already knows all about them: the interesting part would be the way he expresses what it was like to live those stories.

What is it like to look up at night and believe that the lousy white pizza painted on a firmament no more than a kilometer or two away is what people call the "Moon"? How does it feel to have people constantly do product placement to your face? When all the conversations you've ever had were partly or fully scripted and performed by actors, including your family and closest friends, what persistent state of mind does that induce in you?

Now, that's a description I'd love to read: a journey into another human being's radically different perspective on reality. But what if I could write something equivalent myself?

Like this hypothetical post-Show Truman, I've recently found that the experiences I took for granted in the first three decades of my life were less "normal" than I had thought. I have what neuroscientists call aphantasia, a complete lack of visual imagination: the way I think and interact with reality, it turns out, lacks something that the vast majority of people would swear they couldn't live without. It's as if I had grown up in the artificial world of The Truman Show—not as the protagonist, but an unwitting extra—convinced, alongside a minority of other extras like me, that nothing was amiss, only to find out suddenly that this is not what the others mean when they speak of "a normal life".

In my case, the dome of ignorance was not a fake sky physically blocking my escape, but the constellation of words we use to talk about cognition.

The biggest barrier, I have found, was the host of assumptions we make regarding imagination. On my part, I never suspected that imagination might need mental images to be called such; for everyone else, apparently, there was never a doubt of the opposite. Upon first hearing about my aphantasia, people often take that to mean that I am incapable of imagining. After all, the word imagination itself contains the word "image".

Are aphantasics like me, then, the ultimate realists, minds helplessly pinned down to earth, caged in a world composed of nothing but the concrete objects in front of their eyes, cut off from the wonders of daydreams and legends? The answer is "no", but to understand it we need to be clear on what we mean by imagination. The definition might differ from one human being to the next, but that doesn't make one person's definition inherently better than another's. Different doesn't mean abnormal.

I will begin, then, with a description of my own different sense of what a "normal" imagination has been like throughout my life with aphantasia. Only after seeing what life feels like from a different perspective will we be able to talk about imagination and consciousness in a broader sense of those words.

Yep, Sounds Normal Enough!

The irony is that fantastic worlds were always my favorite kind of place. As a small child, I relished my bedtime, when my father would tell me a new fable every evening. Like most children that age, I spent most of my afternoons playing with toy soldiers and knights, action heroes venturing into the lairs of villains, enacting adventures and building new worlds for my own amusement. Never did I realize—not to mention worry—that my imagined worlds lacked the visual element that other kids had.

One day, when I was eleven or twelve, a relative gifted me with a book titled The Hobbit, by a certain J. R. R. Tolkien—I had never heard that name before. It told the story of a little man named Bilbo Baggins going on an adventure across a vast, complex continent, Middle Earth. I enjoyed the story, but it was that world that really struck me. It felt to me as real and meaningful as the one I lived in, if not more. The fact that all of it—its geography, its peoples, its languages and history—could have been created out of thin air by a single mind astonished and exhilarated me.

The Hobbit was my gateway to the fantasy genre and to the more nerdy side of me. Soon afterwards, I read The Lord of the Rings trilogy and was hooked forever. I read those books over and over, and later devoured their (then-new) movie adaptations with the same enthusiasm. I remember asking a friend to open a page at random in the trilogy and read any single sentence out loud. I knew the books well enough to correctly guess, every time, the name of the chapter containing that sentence. I engaged in long, un-planned re-enactments of entire scenes from the movies with my school mates, and co-authored whole cosmogonies and mythologies for our own imaginary universes.

We also started playing fantasy-themed games—chief among them a tabletop role-playing game called Dungeons and Dragons. We would gather at someone's home, sit around a table with pen and paper, and spend hours impersonating dwarves, elves, and wizards in a Middle-Earth-like fantasy world. Everything was done with words only: brief descriptions of the environment and monsters around us, of the actions taken by our characters, and of the complex battles with our foes, were all we had to work with. We filled in most of it with our fantasy. It felt as if I was there myself, immersed in that fantasy world. None of it, of course, was visual in nature, but it didn't seem to diminish my enjoyment compared to my friends.

My craving for alternate realities was not limited to elves and dragons. I was always an omnivore reader. I adored the science-fiction worlds of Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, and Michael Crichton, the historical accounts of Magellan and other explorers of the Age of Discovery, the Victorian London of Arthur Conan Doyle and the comedic mundanity of Japanese school life. Like a seasoned multiverse traveler, I loved the feeling of being yanked into a very different reality every time, governed by different rules and values, and all of it felt natural. It felt like an essential way of being me.

Applied Imagination

Imagination was not only a means of entertainment for me. The studies I pursued—physics, astronomy, aerospace engineering—benefit from a strong ability to simulate reality in my mind. Even though these disciplines are founded on mathematical formulas and the algebraic manipulation of symbols, it would be very difficult to follow them without a strong intuition of how those physical mechanisms actually unfold.

One thing is remembering that the distance of a planet from the Sun follows Kepler's first law, , another thing is understanding intuitively what it means for an orbit to be elliptical, and how a change in its eccentricity parameter (epsilon) affects its shape and behavior. You need to somehow recreate the orbit in your head, and learn how it changes as you change the values in those mathematical symbols. Perhaps surprisingly, the spatial component of my imagination is intact, so I was able to do that kind of mental simulation just fine even without seeing any of it in my mind.

For example, I had to apply my imagination when I pursued my PhD research at the Japanese Space Exploration Agency (JAXA). They were planning a deep-space mission, called Hayabusa 2, that would send a probe all the way to an asteroid, pick up a sample of its rocks, and bring it back to Earth. My job there was to explore the possible orbits that the spacecraft might use to park itself around that tiny asteroid. To do that, I had to throw away all I knew about the neat circular and elliptical orbits famously studied by Kepler: an asteroid's mass can be so small that even sunlight might exert a stronger force on the probe than gravity, wreaking havoc on all the neat equations we normally use for planets around the sun.

As a matter of fact, most of the closed orbits around such a tiny asteroid were yet undiscovered. My project was a computational exploration of whole "families" of such orbits. Instead of simple oval trajectories flatly laid out on a plane, my algorithm returned shapes that looked like lotus and strawberry flowers, fish, fishhooks, spaceships, water fleas, and other three-dimensional paraphernalia. To find them, I had to convert the speed and position of the probe into the coordinates of an abstract mathematical space of six dimensions, and simulate its movement in search of shapes with special symmetries that would allow the trajectories to close onto themselves, repeating indefinitely. For months, I traced the branching lineages and relations of those families—how a circle morphs into a flower, then into a hook, for instance.

This was a highly visual exercise on the computer screen, but my non-visual imagination somehow worked just fine to understand and make predictions about it. I suspect it has to do with the brain's sense of space, a distinct imaginative capacity from visualization that I am perfectly capable of. The science behind this, unfortunately, is still unclear.

Over the years I moved away from academia and shifted my attention back to earth. I grew interested in the design and development of software products, like online platforms to access satellite imagery and mobile applications for financial institutions. As the product manager, my role within the team was to work out precisely the goals of that software, and to ensure that we achieved them quickly and at a low cost, all while offering a pleasant, meaningful experience to the users.

This was quite a leap from my previous orbit research, but at least one thing hadn't changed: I still had to put my imagination to hard work. You can't make a product that someone else loves to use without putting yourself in their shoes and pretending you're facing the same problems and situations they are facing. I spent weeks at a time immersed in hypothetical scenarios, impersonating my target customers. I sat in Japanese corporate boardrooms as a graying manager, struggling with my less-than-sharp tech savvy to navigate multi-layered map interfaces; I rode motorcycles on dusty Sri Lankan highways as a microfinance loan officer, tracking my daily route of customer visits on a tablet terminal; I returned to my home-on-stilts in rural Cambodia after a long day of work at the local textile factory, and looked at my husband's smartphone—the only one in the family—to remind myself of my outstanding loan balance. These flights of the imagination from the office were fundamental for my job, because there is a limit to how much time one can spend directly observing the customers and asking them questions.

Imagination, in other words, was always very much at the center of my experience. In nine cases out of ten, when someone asked me to imagine a hypothetical scenario, I had no trouble with it. When I said things like "I imagine that must have been very exciting" or, metaphorically, "picture yourself on a stranded island", no one ever batted an eyelash. When (a little patronizingly) I suggested my wife take fewer pictures of landmarks and moments and instead "impress the image into your mind by experiencing it directly" (I can't believe I actually said that), she admitted that it sounded like wise advice (then snapped another dozen pictures on the spot).

Communication appeared to be happening as expected. We were, I firmly believed, on the same page on the topic of imagination. In retrospect, though, we really weren't, and I might have guessed it. I realize now that there was also a certain amount of cognitive dissonance on my part.

Omens

Take the last one and a half stanzas of William Wordsworth's I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud, following a melancholic description of "a host of golden daffodils" stretching, in the thousands, near a lake:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

what wealth the show to me had brought:For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

That he could imagine going back to that place and describe what he saw there sounded ordinary enough to me—but what did he mean with "they flash upon that inward eye"? What kind of wealth is he talking about? That seemed like a rather puzzling way to put it, one I would never think of writing myself (even assuming I had the poetic talent to do it). I could write that I enjoyed very much being there, and that I would love to visit the place again, but the pleasure itself ended when I physically left the meadow. The feeling it incited in me is gone now. The bliss of solitude?

This happens a lot. I don't remember what I thought the first time I read, a long time ago, mysterious passages like this, but I must have filed them away in my mind as fanciful figures of speech, the kind of metaphor sometimes dreamed up by an eclectic artist. The idea of seeing with one's "mind's eye" sounds strange to me if I take it literally, but not stranger than claiming that someone has a "heart of gold" or that "you are my sunshine".

There were other hints that something was different about me, although I never made a connection with visual imagery. When I was looking for my first job, I kept getting screening questions about specific episodes of my past experience, like "write of a time when you faced a complex problem in your work, and how you applied reason and initiative to solve it." I just couldn't do it. Even when I was given whole days to reflect on it, I failed to come up with good episodes from my own life. I was quite sure that I had faced some problems in the past, and that I had solved at least a few of them, but none surfaced when I needed them. I had to ask my friends and read old notes and reports to cobble together an answer, and even then I somehow knew it wasn't the best example I could give.

Then there was the question of emotions. Most other people are so wonderfully emotional. They laugh hard and cry often, they look sad or brooding or excited most of the time. Some do a good job at masking that, but will open up in more intimate circles, or explode when they can't take it any more. Others swing continuously from one colorful mood to another. I've always observed these changes with surprise and, every once in a while, with a (muted) tinge of envy.

My own emotional life is the epitome of stability. It's the golf cart to other people's roller coasters. I am very lucky to be stuck in a moderately optimistic state of mind most of the time, and I have experienced extreme emotions—both positive and negative—perhaps half a dozen times in my life (although my poor memory of specific episodes might lead me to under-count). My family and I always attributed this difference to "personality", and left it at that. But was it really a random trait?

This was, and still is, my normality. Even the few areas that were to me incomprehensible at first, like talk of a "mind's eye", the recollection of past episodes, and strong emotions, were gradually subsumed into my definition of "normal" as I grew older and adjusted to society. I rationalized them away, explained them as random and disconnected idiosyncrasies of life, and even came to embrace them. Normal, I believed, is what everyone takes for granted.

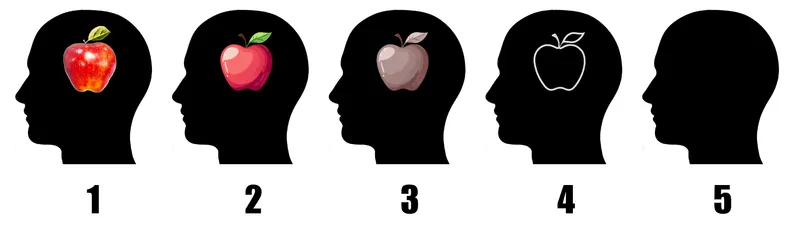

"Imagine an Apple"

Then, on a day like any other on my thirty-seventh year that normality, I learned about the existence of aphantasia as a cognitive trait. Almost immediately, I knew that its description closely matched my own experience. Now that they mentioned it, I had never actually "seen" anything voluntarily in my mind, in the sense of perceiving shapes, colors, and visual details that aren't in front of my eyes. Nor, for that matter, had I "heard", "touched", "smelled", or "tasted" anything mentally. Did they mean that other people could do those things?

It was as if a community of reputable scientists had demonstrated, incontrovertibly, that most people actually have hearts made out of 24-karat gold, and I was one of the very few who didn't.

Or as if they had just told me the world I knew was all an immense film set.

My first reaction was one of dismissal, or perhaps denial. I told myself that, even though I might have aphantasia, it didn't really matter. It was a mere curiosity. "I function as well as anyone else in society," I thought, "so what difference does it make how I do it?" I didn't read much further about the condition. I mentioned it only in passing to a few friends, then forgot about it. My normality continued.

Only about one year later, when I saw aphantasia mentioned again on various social media and scientific papers—now more often and in depth than before—I thought about it for a second time. I started reflecting on it, on my own inner life, more seriously. I began reading extensively about the science behind aphantasia, and found online communities of people in the same situation. We discussed, compared our subjective descriptions, and gradually mapped the similarities and differences between the aphantasic experience and that of everyone else, as well as those between different "flavors" of aphantasia.

I also got in touch with researchers involved in its study, and took the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), the standard scientific test to measure the power of the mind's eye—for the time being, the only way to detect aphantasia outside the lab. The VVIQ brought further confirmation to my hunch: I very probably had aphantasia.

In this initial phase, which unfolded over the course of several months, the true implications of aphantasia, both for myself and for humanity as a whole, finally began to dawn on me.

Epiphanies

First, I realized that there were many more individuals like me, and that they were as puzzled and fascinated as I was. I learned that most people are indeed capable of "dancing with the daffodils", recreating visual scenes and faces in their minds like an order of discreet wizards.

I also learned that they tend to rely heavily on that ability—so completely, in fact, that the idea of not having mental imagery sounds like a crippling handicap to them. And yet, while I do feel somewhat different, I don't feel disadvantaged in the least. This paradox might be explained by some very recent science, showing that people can employ different mental strategies to solve a cognitive task. Aphantasics may have their own non-visual ways to think things through.

By knowing about this condition and the science behind it, I can more effectively find those alternative strategies that make my aphantasic life easier. But aphantasia science is barely ten years old: had I been born a mere fifty year earlier, in all likelihood, I would have lived and died without ever knowing about aphantasia and all of the subtle effects it has on aspects of my consciousness. In this sense, I was lucky to be born when I was.

After a moment of complacency, though, another thought arises: what other fundamental aspects of what makes me who I am are going to be discovered in my lifetime? Which key mental traits will get their own names and internet communities only after I am gone? This is hardly about me alone. Think about all the other people who currently believe they are "normal"—trying to fit in by sweeping their perplexities and unexplained personality differences under a rug (or dome) of ill-defined words.

How many people who consider themselves mentally "typical" will soon discover that they are actually part of a cognitive minority in one way or another?

Ten, fifty, a hundred years from now, will there be anyone at all left in the general category of "neurotypical people"?

I was finally convinced: this was not just a curiosity about me, but a big deal about everyone else, too. Scientists have been studying mental imagery for decades, because they believe it is a key to understanding other core functions of the brain, such as vision processing, attention, and spatial awareness. Now that aphantasia is known, the experimental comparison of people with and without mental imagery has become a powerful new method to answer those old questions.

When my Japanese neuroscientist acquaintances asked me to join some of their experiments, I immediately accepted. By letting them study my brain, I knew I could help them deepen our understanding of aphantasia itself, as well as those other major questions about the human mind.

There Is More Yet

At that point, I thought I had learned most of what I needed to learn about myself. Although there were still some scientific and social ramifications to be explored, for a while I believed that was, essentially, it: my mind is non-visual, undisturbed by sensory embellishments.

Of course I was wrong. As I took part in long experiments over weeks and months, completing tasks inside fMRI machines and in front of computer screens, I had the opportunity to reflect on my conscious experience more thoroughly, and I researched the matter in depth. I learned the rudiments of introspection: tuning my attention into how I think, rather then what. With that new skill, I entered a new sequence of small epiphanies.

I realized, for instance, that my abysmal episodic memory is a trait I share with many other aphantasics, called Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory or SDAM; I learned that what I considered to be my "emotional stability" might be a mild form of alexithymia, the difficulty in noticing and identifying one's emotions, also common among people with aphantasia; I noticed, for the first time, certain qualities of my dreams that I had never noticed before; I also observed how my strong sense of direction helps me, how my lack of imagery affects my creativity, and the ways I can work around those obstacles.

Some of these things I have already written about, others I will in the future. I don't know what happened to Truman after he escaped the TV dome, but I suspect it was a long and fascinating journey. My own journey certainly is. ●

Cover image:

An original theory or new hypothesis of the universe, Plate XIII, Thomas Wright