POSIWID

A mosaic

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Small pear tree in blossom, Vincent van Gogh

I

If your pants keep sliding down as you walk, you tighten your belt. The intention is for them to stay up at all times, but it takes a structural change—a tighter belt through its loops—for the intention to be realized. Until then, they are Slide-Down Pants.

If people keep on dying in the same curve in the road, month after month, the transportation authorities add warning signs, reflective arrows, rumble strips, and guardrails. They might even change the shape of the curve. All along, the intention is for the road to leave the people that pass through it alive and unharmed, but it takes a structural change for the intention to be realized. Until then, it is a People-Killing Curve.

If a forest keeps catching fire, burning homes and destroying ecosystems and polluting the air, the forest and conservation authorities thin out the trees, create buffer zones and firebreaks, do controlled burns, switch to fire-resistant construction materials, and encode fire prevention habits and response plans in the synapses of the nearby people. The intention was never for the forest to wreak havoc. It takes a structural change for the intention to be realized. Until then, it is a Catastrophe Factory.

II

If I'm a prisoner in a labor camp, my intention isn't to help my oppressors. On the contrary, my intention is to leave the place forever, and to have nothing to do with them. Yet there is a structure in place that makes me comply with their intentions. This structure is made of mechanisms that detect my disobedience and trigger retaliation, such as violence and deprivation of food, sleep, and comfort. For my oppressors, the camp is working as intended. For me, only a radical change in structure—such as entirely removing myself from the camp—would make it align with my intentions and needs.

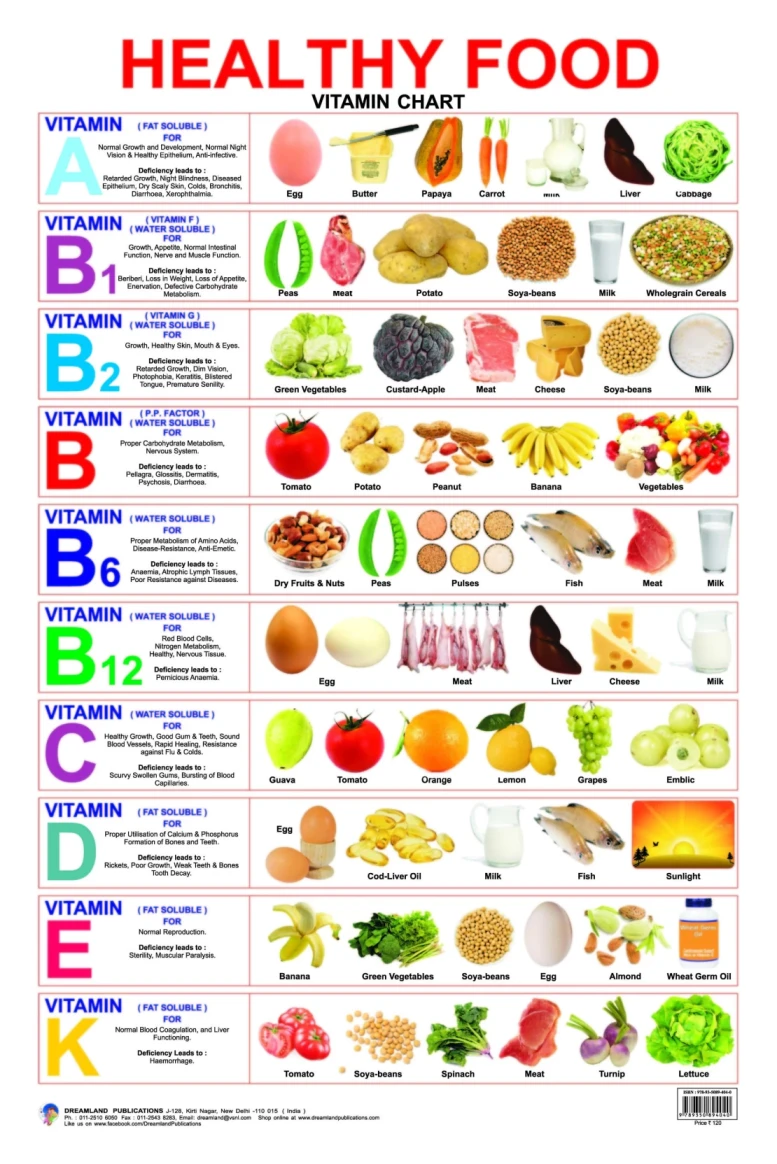

If you're a plant, your intention isn't to be reduced to a single checklist item on a human's vitamin chart.

As a plant, you don't have an intention, but your genes have something analogous: a plan for growth, reproduction, cross-pollination, speciation. Yet there is a structure in place that makes you comply with those human intentions. This structure is made of mechanisms that redirect your seeds, detect your deviations from an imagined ideal, and relocate your fruits and leafs to the other side of the world. For humans, your species is working as intended. For you, only a radical change in structure—your seeds escaping into the depths of wilderness—would make it align with your genetic tendencies.

If you're a political party, your intention isn't to be led by incompetent people. On the contrary, your intention is to select the individuals best suited to lead a nation and to solve its multifaceted problems. Yet there is a structure in place that makes you filter out the competent people and promote the unqualified. This structure is made of mechanisms that detect the fanatic and irrational responses of the crowds and trigger more of the actions that caused them, and mechanisms that sink the parties that do that less effectively. Moreover, the intention of the incompetent people is often different: to lead the party. For them, the party works well enough with the current mechanisms, if not perfectly. For you—the party as a group—only a structural change would make politics align with your intentions. Until that happens, you're a Moron-Selection System.

III

In 2017, near the southern entrance of the Suez Canal, a sailor called Mohammad was aboard a container ship when he put his name on a piece of paper.

A court courier had come with a letter declaring that the ship was being put on hold until an unpaid bill was cleared. The captain was not on board that day, so Mohammad, the second in command, signed the letter as the legal guardian of the ship. That signature marked his fate for the next four years.

Mohammad had nothing to do with the unpaid bill. The owners of the ship, the people who should have sorted the matter out, did nothing. The ship remained there, anchored off the coast of Egypt, without permission to move.

Gradually, the other sailors on the container ship returned to their home countries. When Mohammad tried landing himself, the police took him back to the ship: he was the legal guardian. After two years of living in that artificial island, the last of his crew-mates left and Mohammad remained completely alone on the giant vessel.

At one point, the ship began to sink. He called for help via radio, and hoped he'd finally be released from his entrapment. The people on land repaired the ship's hull and kept him locked up.

When Mohammad pleaded to be put in a prison—a more enticing prospect for him than complete isolation in the middle of the sea—he was told that they couldn't do that, because he had done nothing wrong.

During those four years, first Mohammad's mother, then his grandmother died, and all he could do was mourn them from afar, with no one to console him. The ship's owners sent him food and supplies, but they were less than steady in their shipments. Often, dried bread was all he had to eat.

Mohammad was finally allowed to leave his dusty, insect- and rat-infested, barely-floating home in 2021, when an International Transport Workers’ Federation found a volunteer to replace him as legal guardian of the ship.

This wasn't an isolated Kafkian episode. "Seafarer abandonment" is a thing. In 2023 only, 143 new cases like Mohammad's were reported around the world, with more than 270 simultaneous cases still unresolved. The pattern is the same: legal or visa-related circumstances prevent the crew from leaving the ship, the ship can't be moved, and the people really responsible for the problems are somewhere far away, unconcerned or unhurried. The sailors are often left without salary, innocent but stuck in a gridlock outside their power to resolve.

All along, it was never the intention of those laws and practices to detain innocent people in pitiful conditions. A structural change might avoid that outcome in the future. Until then, those ports are Prisons for Innocents.

IV

According to the cybernetician, the purpose of a system is what it does. This is a basic dictum. It stands for bald fact, which makes a better starting point in seeking understanding than the familiar attributions of good intention, prejudices about expectations, moral judgment, or sheer ignorance of circumstances.

— Stafford Beer ●

Cover image:

Small pear tree in blossom, Vincent van Gogh