Determinate Self-Sabotage, or Obsessive Connoisseurship?

On the quandaries of kodawari

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Edu Grande, Unsplash

I used to go to the movies often. I used to buy four or five books every time I entered a bookstore—another frequent occurrence. In my early twenties, entertaining myself was easy. I learned Japanese entirely by entertaining myself: hundreds of manga volumes, dozens of anime series, scores of novels. Fantasy sagas, space-faring action flicks, slices-of-life, voyage chronicles, meditations, mysteries, thrillers, romances, ninjas and pirates.

Then, without me even noticing, the range of things capable of entertaining me shrank. I began to exercise some discretion. The flaws of a creative work revealed themselves to me more often, then all the time. Most Hollywood flicks lost their appeal. Best-seller-strewn show windows ceased to excite me. Other people's recommendations rarely worked out. Nowadays, I read more and more classics—not because I don't believe good contemporary works exist, but because the effort of wading through the noise can be very tiring.

My Japanese wife calls this state I'm in "a strong kodawari" for storytelling.

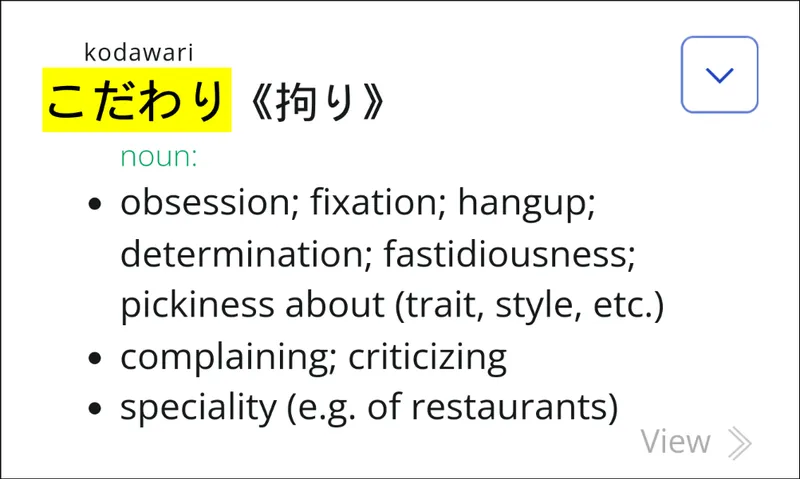

In English, you would have to call it a "fixation" or "obsession" with a certain style of storytelling. You could say that I'm "particular" about the consistency, structure, and depth of stories. But all of these English terms fail to convey the efficient subtlety of the Japanese word kodawari. Look at a Japanese-English dictionary, and kodawari appears to be a plain translation of those words: a mildly negative state of mind where someone stubbornly—sometimes even illogically—refuses to compromise on something.

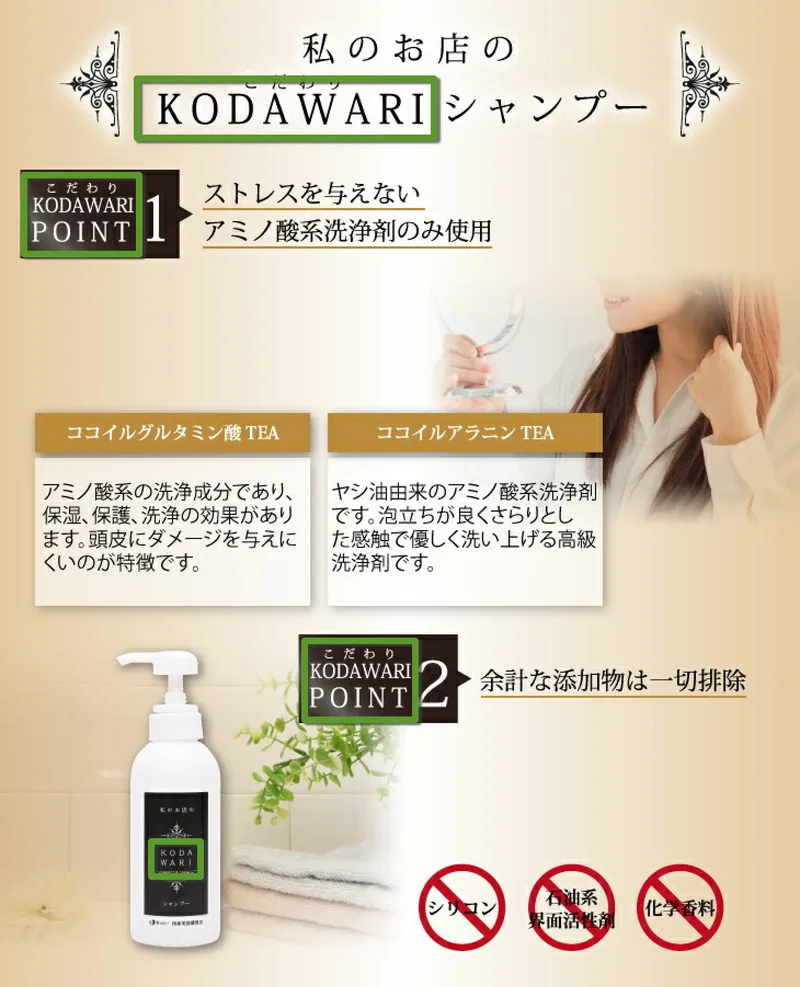

But, unlike its English counterparts, kodawari is regularly used in a very positive connotation: that of resolutely—sometimes even heroically—refusing to compromise on something. You can guess that by how many ads use the term to talk about their products.

These marketers don't mean to say that they're unhealthily obsessed, hung up, or in a criticizing attitude with their products. Their kodawari is meant to be a big selling point.

According to the Japanese, the best of the best all have very strong kodawari in their arts. A Japanese magazine uses the word twice in a paragraph describing Hayao Miyazaki's work: that he "insists" (kodawari) on creating textured films and "resolutely sticks" (kodawari) to hand-drawn animation. You'll find dozens of Japanese blog posts about the many kodawari of Steve Jobs (for example, here): he was a fructarian and ate mostly apples, he had strong opinions on the placement of bathrooms in office buildings, and insisted that one should be explicit about what they won't do.

Alright, kodawari must have a neutral flavor, then. Perhaps "a refusal to compromise (on something specific)" is the English phrasing that comes closest to replicating that neutrality. This isn't very helpful. When is it a good thing, and when is it bad? Am I better off compromising on as many things as possible, or should I avoid it? I find these questions incredibly difficult to answer.

Somewhat paradoxically, these doubts disappear in the context of achieving greatness. I find it easy enough to believe that, to be as impactful and famous as Miyazaki or Jobs, one has to be more than just discerning with their work—that one needs to be adamant about the precise way they do their thing, and more so than their peers. It may not work every time, but it does seem like a prerequisite for success.

No, what I struggle to form clear ideas about is the mundane, unambitious kind of kodawari.

I remember the awe I felt towards some of my friends back in university, who could at a moment's notice pull out a guitar or keyboard and entertain us all with exciting, deep, skillful music. For someone like me, whose only musical output was a few lame recorder tunes during music class in middle school, those friends were nothing less than wizards.

Of course, to achieve those levels of skill, they had practiced almost daily for years, trying to strum their favorite songs time and time again, alone in their rooms, noticing everything that was wrong in their delivery and fixing it one shade at a time. They had to develop not only excellent coordination of their fingers but also a very discerning ear and a refusal to compromise for sounds that were "barely recognizable" or even "decent." Their kodawari for flawless performances is what propelled them into the realm of what I considered to be wizardry.

At the same time, many of those same virtuoso friends were unable to enjoy 99% of the music that could be found on radio stations and in CD shops. Most songs were too "commercial" or too "derivative" for them. They worshiped Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin, Chopin and Mozart—and I'm sure they were able to enjoy those artists more deeply, more viscerally than I could, thanks to their refined ears—but they were also trapped in a noisy, bland musical world by precisely the same kodawari.

I see this all around me: in how my well-dressed wife will suffer cold and heat rather than use layered clothing due to a strange kodawari; in how a stylish ex-colleague precluded himself from working in any company that didn't have an elegant office in a posh part of town; in how some audiophile friends of mine are unsatisfied and frankly a little irritated by any encounter with cheap or sub-par speakers; in how Italians, French people, and really most of the rest of the world don't seem capable of enjoying British food.

Sometimes, when I witness the extent to which others go just to avoid compromising on their passions and pet peeves, I almost feel lucky not to be like them. By not having a kodawari for drinks, for example, I effortlessly avoid alcohol and coffee, two of the most widespread addictions of modern society: water is my favorite drink. By not being very discerning with brand value and status displays, I never feel the need to splurge on luxury items, saving myself who knows how much money over my lifetime. The same goes for spending on hi-fi tech, because I'm perfectly happy with—blissfully unaware of!—the mediocrity of any audio source.

When I observe these facts, I find it hard to imagine how any extra enjoyment of 1% of a given category, afforded by the refinement of a kodawari, can possibly outweigh the loss of satisfaction for the remaining 99%. In these cases, it seems to me that a deep-seated refusal to compromise on something is a net liability, a handicap toward the goal of enjoying one's life.

It's easy to say such things about others' lives, though. Perhaps it is even irresponsible. What about my own kodawari?

I already mentioned how I learned Japanese by being an entertainment omnivore: for a few years, I immersed myself in Japanese media, ranging from children's books to mildly popular rock music, from trashy anime to slapstick comedy. Very few things bored me. While I did draw a line at certain points, I was able to find sufficient delight in a wide variety of Japanese-language sources, and this helped me immensely. If I go back to those same works today, I find that I'm unable to derive any satisfaction from most of them. Those books, anime, and artists have lost all of their appeal to my eyes. I've grown too picky, too particular about how I use my time. I'm afraid that it would be much harder to learn a new language with this kodawari I've developed for myself.

In my late twenties, I went through a rather insufferable phase in which I would point out to my partner and friends all the ways a movie was bad and unpleasant—right after we were done watching it. Needless to say, this annoyed the others, especially when they had enjoyed the film.

For a while, I thought those people were being unreasonable. How could they deny those inconsistencies or blatant clichés? Then I realized that my criticism was annoying not because, or when, it was wrong, but precisely because and when it was right. What I was really doing was making flaws and warts stand out for people who hadn't noticed or cared about them while watching. Warts and flaws which, if I was right, those people couldn't unsee. In other words, I was ruining their enjoyment.

I stopped doing that a long time ago. If a fellow movie-goer asks me directly what I thought of the film, I will tell them vaguely whether I liked it or not—expanding freely on the parts I feel like praising—but I won't volunteer any specific criticism before my interlocutor. Everyone has the right to enjoy a creative work at the level of sophistication they want. And, I admit, sometimes I wish I could turn off the "story analysis device" in my brain, sit back, and fully savor whatever blockbuster most other people are raving about at any given time.

All of this doesn't sit comfortably with me. When I put things that way, even my own kodawari feels like a handicap, an obstacle to fully enjoying whatever is available to me, rather than only those things I have painstakingly selected. But if you were to offer me a magic pill that really removes, permanently, that "story analysis device" I have honed over a lifetime, I don't think I would take it. Why? Because writing stories, fiction or nonfiction, is what I have chosen as My One Goal in life. If I ever write a great piece of writing, it will also be thanks to this kodawari, the same one that robs me of some fun in other areas. It is a blessing with a price I am willing to pay.

Here we are again on the topic of greatness. Perhaps having a kodawari is a net positive only when it is related to Your One Goal, or one of a few, and not worth it in any other case?

Or is there an artful way of developing a kodawari that can be toggled off or dialed down when needed—a way to raise your ceiling of enjoyment without affecting your floor—a breadth-preserving pickiness?

I wish I knew. But the more I think about this, the more I feel like I should be discerning about my discerningness. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Edu Grande, Unsplash