The Luxurious Pain of Using My Time

Possibly just me coming out as a lucky optimist

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

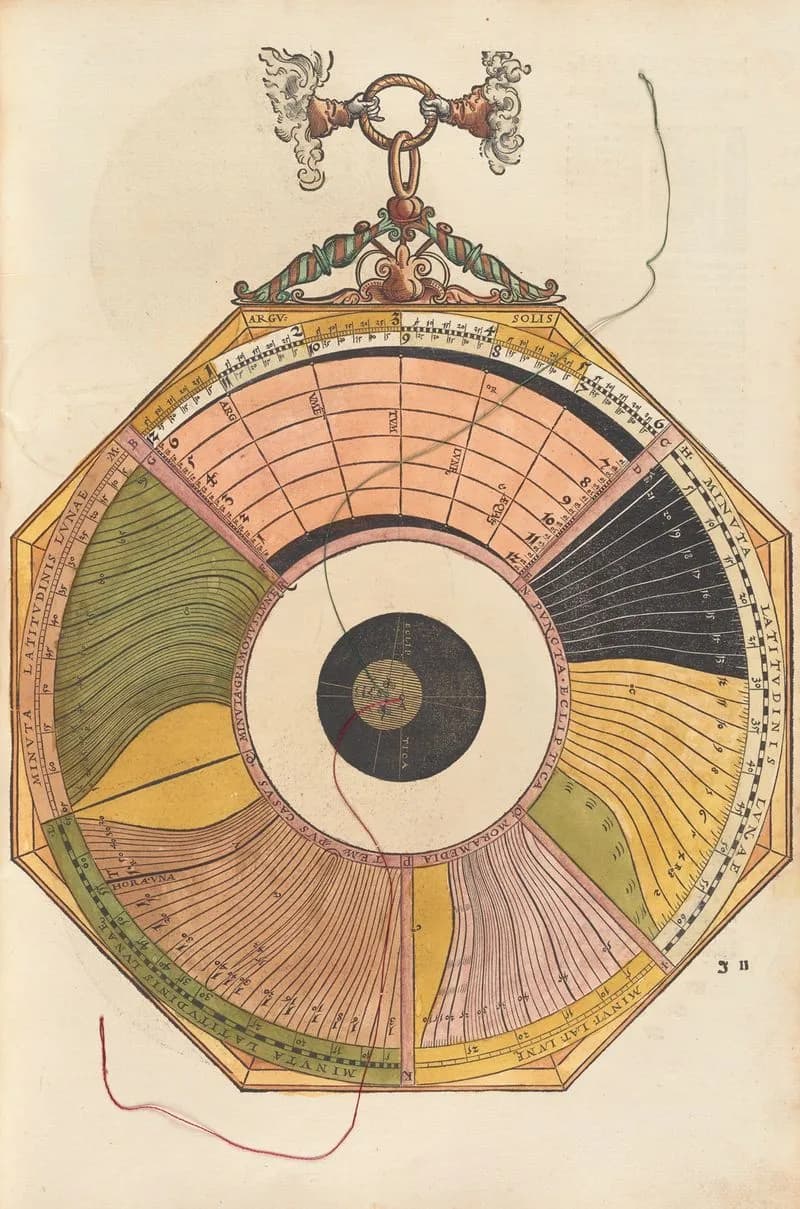

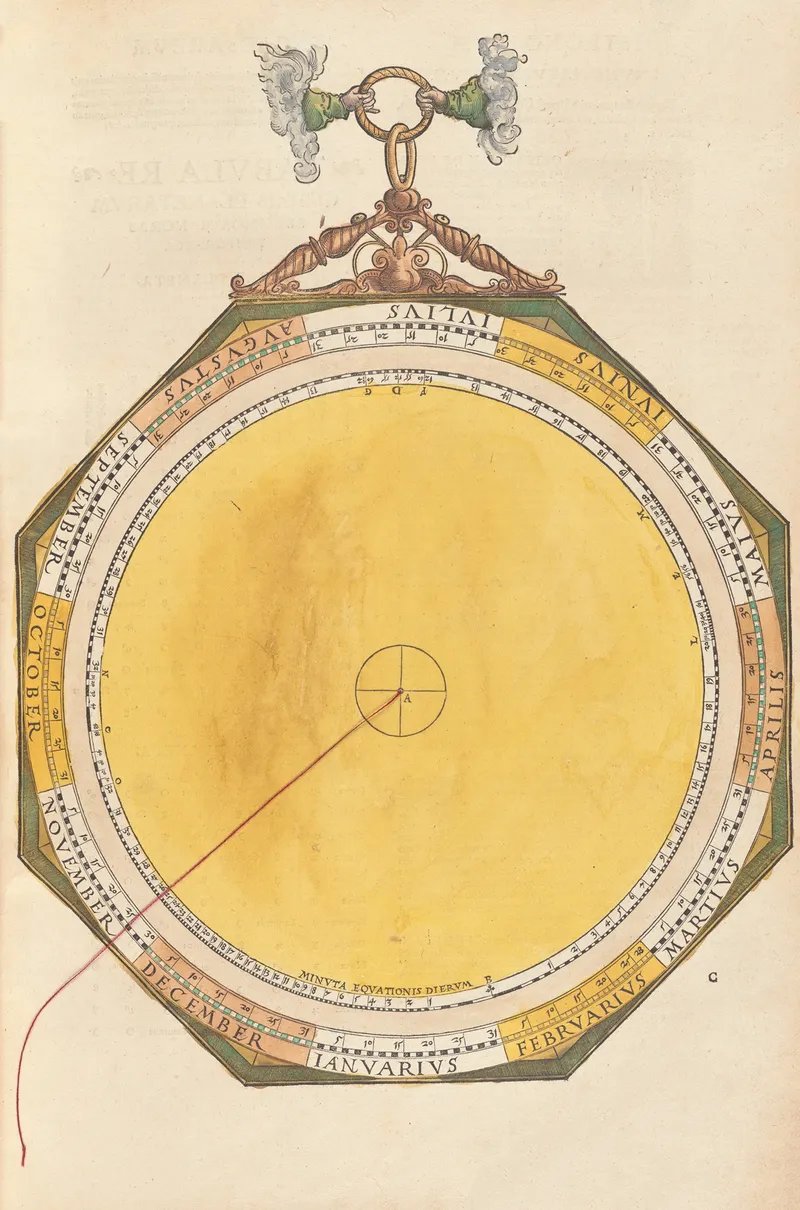

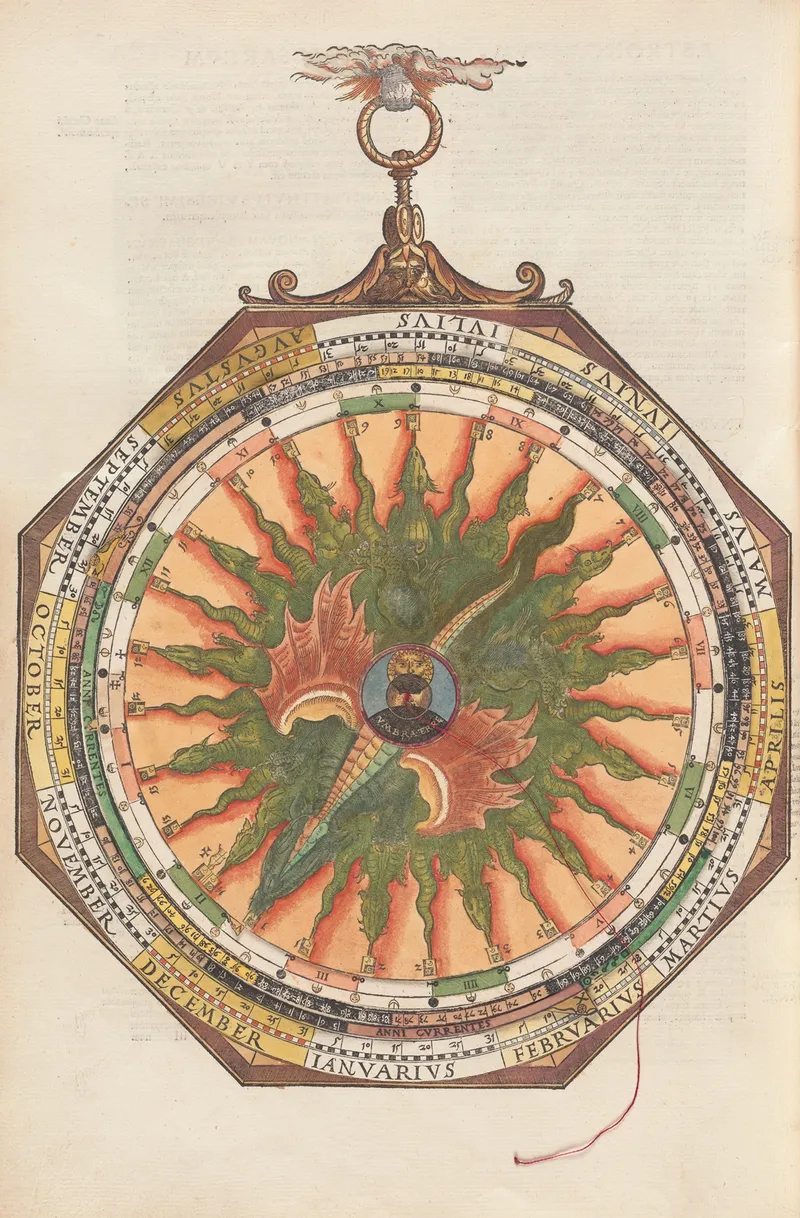

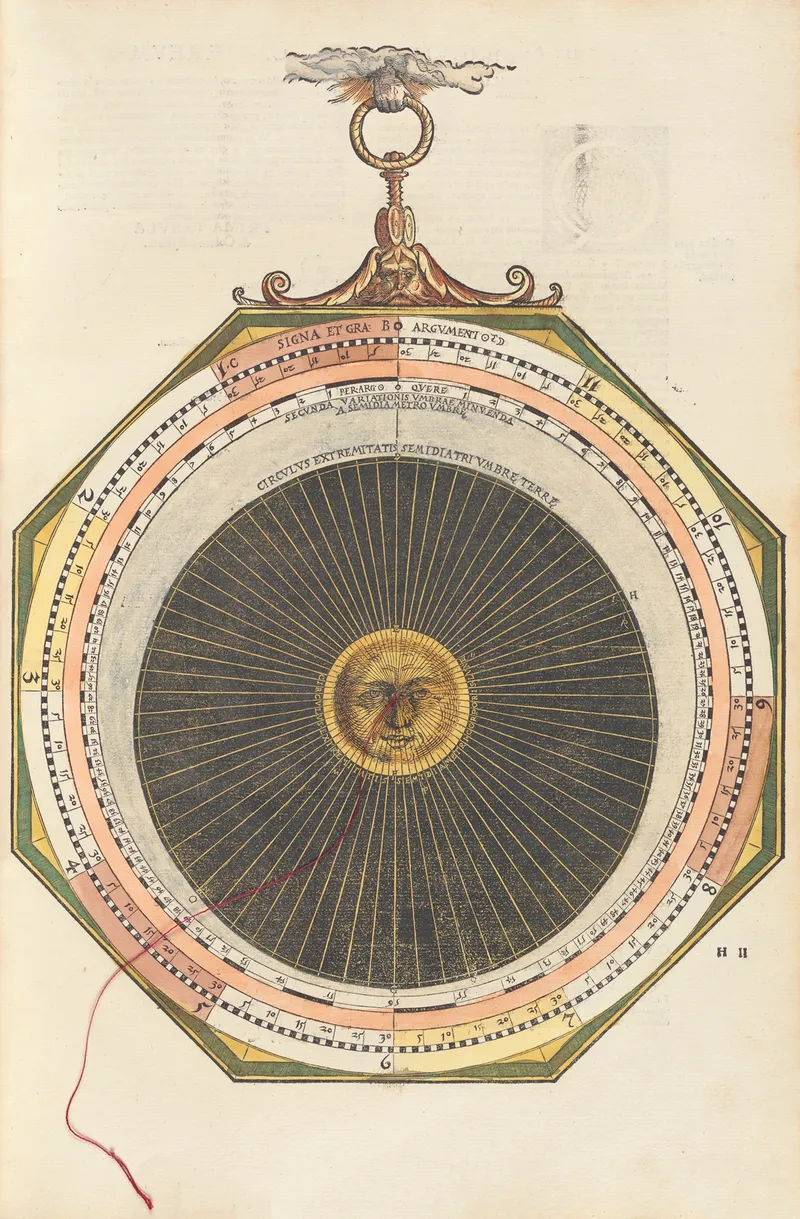

Cover image:

Astronomicum cæsareum pl 028, Petrus Apianus

About the Pain

Sometimes other bloggers read Aether Mug and are kind enough to tell me that they like it, that they've read several posts, and that they'll be reading the next one. They comment on what I wrote, engage in interesting and cogent conversation, ask me follow-up questions. This obviously brings me joy, because it's a kind of connection that I hope to spark with my writing.

But this joy is often tempered by a kind of pain: I seldom reciprocate by following their blogs. This is not necessarily because I don't appreciate their writing. I won't even follow blogs that I genuinely found intriguing and well-crafted. I may read a couple of posts by them because I want to be able to expand the conversation. More often than not, though, I decide not to add them to my regular reading feed.

This is a painful decision every time, and not only because it can make me feel unfair or rude ("I'm too picky to follow your writing, but you can follow mine if you want!"). It stings because it is a very conscious sacrifice on my part, a loss that I impose on myself because I have too many things to read already.

This is a manifestation of a bigger phenomenon encompassing all forms of reading. People and algorithms recommend fantastic books, essays, and articles, and I want to read them all. And the more I read, the more ideas I get for further things to read.

There seems to be an inexorable law of nature at work: reading lists always grow faster than you can devour them.

And it's not even something limited to reading or consuming content, either: I have bucket lists of all kinds—places to visit, languages to learn, skills to master—and they are always overwhelming. I'm forced to pick and choose, and that is where the pain arises.

In part, this is only an apparent problem. Those blogs and books, those places and activities already existed out there, and my becoming aware of them doesn't really change anything. It's a bit silly to feel mortified for missing something that I would have blissfully missed if only I had never known about it. On the other hand, whether I know all of it or not, it's a real bummer not to be able to read and do everything I would like to read and do in my lifetime.

For this reason, I consider this an important topic, even if it is composed of tiny, almost insignificant choices like what to point my eyeballs at on a given half-hour.

That might sound like existential anxiety, but it... doesn't feel like that to me. I choose not to do certain inviting things—instead of gleefully throwing myself at whatever sounds fine and interesting at the time—because it is rewarding to do so, every time. Choosing carefully how to spend my time is liberating. It makes me feel like I'm living more intensely.

The Time That Is Given Us

A long time ago, I made it a point to never use the words "I don't have time" to opt out of doing something. Time is the only thing we all certainly have for as long as we live. There is no guarantee that I'll have money, friends, health, or whatever else I desire at a given period of my life, but I certainly have that period of time. The time we have, however, is not infinite, so the real question is not if we have time, but "what to do with the time that is given us" (to use the words of a wizard).

Put differently, whether I realize it or not, at every waking moment I decide to give up on many activities in favor of a few, often only by default. If I tell you "I'd like to exercise more/read more books/learn a new language, but I don't have the time", what I'm really saying is "I've considered doing that thing and decided that, despite its allure, it's not worth sacrificing any of my current activities for it".

It's like packing a holiday suitcase and finding that my volleyball "doesn't fit in": the capacity of the suitcase is not reduced by the clothes I already put in it—I may simply be unwilling to remove those necessary clothes in favor of a ball I may or may not use during my trip.

Consuming media is another choice of what to stuff into the Lifetime Suitcase, and, because media can be really interesting, making that choice can hurt.

Here I'm referring to a small subset of all media. Sure, there is an immense amount of trash content and pointless noise on the internet and on bookshelves—an amount growing even faster since the advent of cheap LLMs—but that's not the problem I'm talking about. Filtering out spam and slop is relatively easy with the right tools and a little thought, at least at an emotional level.

The much tougher job, I think, is giving up on things that would be good, meaningful, fulfilling, and useful in order to do things that are even more so—or, to be precise, to do things that are better aligned with what I really care about right now. The hard part is dealing with the fact that, whatever I may try, I will never get to do the vast majority of those amazing activities.

Dealing With It

I've found that the most satisfying way to manage my time is to make those choices explicit. As often as I can, I avoid defaulting to the first activity that captures my attention or seems interesting enough. Not because those are always the wrong things to do, but because it is so easy to forget about the options that are not currently in the front of my mind.

Purpose is key here. The kind of deliberate choice I'm talking about is only possible when I know what I want, and it gets easier and easier the clearer I am about my goals.

It doesn't matter what purposes I have in mind during a given period of my life, or how relatable they would be for others. Am I looking to switch to a job or industry I prefer? To paint a picture or craft a sentence that will leave at least one person forever changed? To laugh wholeheartedly every single day? To make a thousand people happier? To build a lifestyle that is not hindered or thwarted by a medical condition I have?

Invariably, I have not one but a constellation of many goals. It doesn't need to be about the One Scary and Difficult Life Purpose. Even assuming such a purpose exists, life is not a global optimization game. That's why I talk about goals in the plural. There are always several things I'm aiming for, and I think it's important for me to inventory them regularly. Once I have them in mind, it's not too hard to discern which activities will leave me feeling fulfilled and happy with the sacrifices I made.

The relationship between those purposes is just as important. Each goal is valuable in its own right, but some are more valuable than others. Maybe I really want to learn Korean, but pursuing that goal properly would hurt my goal of spending quality time with my family. If I know and believe that the latter purpose is more important to me than the former, my decision to give up Korean—even only for a while—is the right sacrifice for me. It took me a while but, at some point, I realized that understanding the hierarchy of my goals at a given time is the only way to make good decisions of this sort.

Some might find this line of thinking stressful, like treating one's whole life as a job. In the sense that I apply reason to "manage" my time, maybe that's an apt analogy. But the implication that this would lead to anxiety says more about those people's view of work than about the approach I described above.

First, working for myself feels very different than working for someone else. Having conscious control of what I do allows me to remain focused on what I want, not what some boss or shareholder requires me to do. Second, if the "sounds-like-a-job" analogy is accurate in any meaningful way, it is the kind of job Mark Twain referred to when he suggested to "find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never have to work a day in your life."

Grateful Pain

I suffer a little when I have to choose what to read and what to leave unread. I struggle a little every time I enter a bookstore (my favorite kind of place), every time I receive a good but not spot-on book recommendation or gift, every time I find another hidden gem of a blog that scratches an itch located too low on my "hierarchy of purposes".

Still, it gets easier. The more I exercise my right to carefully manage my time based on my goals and values, the more instinctive those choices become. Sometimes they are almost automatic. Nowadays, for example, I naturally lose interest in video games that turn out to be "just fun", and dropping them has become almost effortless. I've also learned to abandon a book midway through—something I once had huge cognitive dissonance against—when I realize it's not resonating with me.

At the same time, I increasingly experience the immense freedom of being aligned with my own compass, and more intensely than I feel the pain of giving up good things. This further convinces me that it's a lucky pain to have, the happy kind of pain, a luxury to be grateful for. It is a privilege to live in a world and situation where I have the means and options to choose among endless great ways to spend my time. It may not be easy to navigate, but it's not something I will ever complain about.

I don't believe the pain of turning down amazing opportunities will ever completely disappear, because of how human nature works. It comes with the territory, like the frequent soreness in an athlete's body. But I believe it's a pain worth treasuring. ●

Cover image:

Astronomicum cæsareum pl 028, Petrus Apianus