There Is Thinking and There Is Thinking and There Is Thinking

Should we anthropomorphize LLMs?

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Sebastian Hages, Unsplash

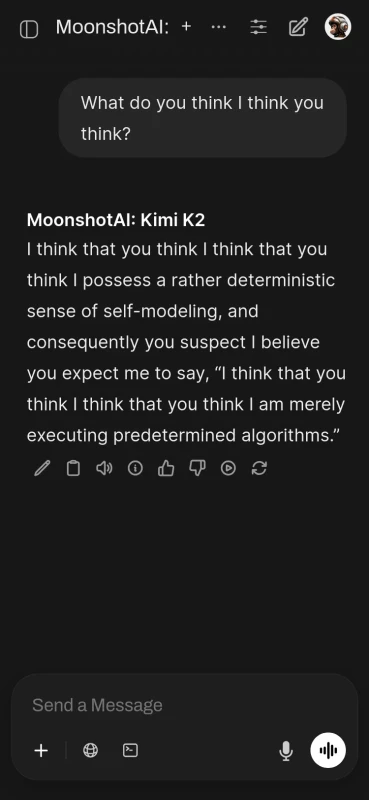

The computer-science-adjacent forum Hacker News had a very interesting conversation going on last month titled A non-anthropomorphized view of LLMs. That is actually the title of a blog post, but (although the post itself is interesting) I was more fascinated by what the Hacker News commenters had to say about it.

halvar.flake, the author of the original post, says that talking about LLMs as if they were people feels wrong to him, and that we should instead treat them for what they are: "mathematical objects" and algorithmic "functions." We must not, he says, use terms like "thinking" and "waking up." He writes:

Instead of saying "we cannot ensure that no harmful sequences will be generated by our function, partially because we don't know how to specify and enumerate harmful sequences", we talk about "behaviors", "ethical constraints", and "harmful actions in pursuit of their goals". All of these are anthropocentric concepts that - in my mind - do not apply to functions or other mathematical objects. And using them muddles the discussion, and our thinking about what we're doing when we create, analyze, deploy and monitor LLMs.

There is no doubt that he is technically correct: language models are literally "transformers" of information in the form of numbers, implemented on semiconductor chips—not evolved organic neurons inside living bodies.

But the top commenter on the Hacker News thread immediately casts doubt on halvar.flake's take with some very compelling points: while LLMs are indeed mathematical objects, they do things that are very unlike most other kinds of math functions, so it is not useful to treat them only as such: "we need a higher abstraction level to talk about higher level phenomena in LLMs."

And since LLMs imitate humans in many ways (continues the top commenter), it is only natural to use human-centered language to describe some aspects of them. It seems to me that they are accusing the blogger of greedy reductionism, the same kind of thinking that would make you say "the Mona Lisa is just a few grams of dry paint particles on a canvas"—technically right, but kind of missing the point.

Although the commenter doesn't say this explicitly, it sounds to me like they're applying a weak form of the duck test to this problem: if it talks like a person and it reacts like a person, then treat it as a person at least to some extent.

This sparked an interesting thread of characteristically blunt-and-polite Hacker News arguments and counter-arguments. Computer scientists might understand anthropomorphic terms applied to LLMs as mere metaphors, says another commenter, and this would make such language mostly harmless for them, but the problem is that the public at large will be hopelessly confused or harmfully misled. Other commenters go as far as proposing the creation of whole new verbs for this strange category of action, to distinguish it both from human agency and from that of "traditional" mathematical operations.

What I find amusing about this discourse is how it mirrors almost exactly the one that has been raging for a hundred and fifty years (and counting) in biology about the applicability and defensibility of teleological—purpose-centered—terminology in evolution. The only difference is that the subject of that debate is not a technology but living things and evolutionary processes: Is it okay to say that a meerkat makes an alarm call because it "wants" to inform its gang about an approaching predator? Did eyes evolve "so that" an organism could see?

Biologists all agree that there isn't really any intention involved in most of these biological facts, unlike when we use those expressions for humans. And that's where the agreement ends.

Many major figures in the field, including Charles Darwin, claim that teleological terms are metaphors, yes, but necessary ones: trying to speak about them in any more "accurate" way would be very inconvenient and, frankly, too much of a hassle, so let us accept the compromise and get on with our work.

This preservation, during the battle for life, of varieties which possess any advantage in structure, constitution, or instinct, I have called Natural Selection; and Mr. Herbert Spencer has well expressed the same idea by the Survival of the Fittest. The term "natural selection" is in some respects a bad one, as it seems to imply conscious choice; but this will be disregarded after a little familiarity.

— Charles Darwin, The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (emphasis mine)

Other scientists and philosophers disagree, insisting that words like "purpose" and "function," and speaking of organisms or species as if they were conscious, intelligent agents, is just plain wrong. For a long time, any mention of teleology was almost taboo among evolutionary scientists.

During my own education, I was repeatedly warned against teleological thinking, and its close cousin anthropomorphism, by lecturers who spoke of the heart as a pump for the circulation of blood and of RNAs as messengers for the translation of proteins. ... Final causes are shunned as fruitless females who remain anathema to the virile vulcans of hard science.

— David Haig, From Darwin to Derrida (emphasis his)

In recent decades, there has been a push-back against this kind of censoring. In an excellent 1997 piece for Discover Magazine, Frans de Waal takes issue with the canonical view that all animals except humans are effectively mindless automata:

If we descended from such automatons, were we not automatons ourselves? If not, how did we get to be so different? Each time we must ask such a question, another brick is pulled out of the dividing wall, and to me this wall is beginning to look like a slice of Swiss cheese.

— Frans de Waal, Are We in Anthropodenial?, Discover Magazine

Someone, hoping to resolve the divide, even created a new word, "teleonomy", to indicate "teleology without conscious intention". How similar this is to the proposal of some of the Hacker News commenters:

We need a new word for what LLMs are doing. Calling it "thinking" is stretching the word to breaking point, but "selecting the next word based on a complex statistical model" doesn't begin to capture what they're capable of.

Alas, even "teleonomy" still hasn't widely caught on, half a century after its proposal and despite many committed proponents. In other words, nothing in this biological conundrum is settled yet, and confusion on the teleology of life still lingers, annoying basically everyone.

Of course, the parallel between biological and AI language choices can only go so far. While we H. sapiens are undeniably linked to all other life forms by at least part of our ancestry, we have no such deep similarity with GPUs flipping bits in their memory registers. In his opinion piece, de Waal can convincingly assert that "the closer a species is to us, the easier it is to [understand the animal's idiosyncratic way to perceive its environment]." There is no "degree of closeness" between us and, say, Deepseek R1.

Still, there are similarities between what modern language models and people do: if there weren't, we wouldn't be able to converse with them! I think many of the hard lessons that biology—confused as the field might still be on these topics—has learned from its own version of the controversy could become useful pointers for thinking about LLMs, too, even if the answer turns out to be different.

De Waal himself, for instance, shows due care in not overdoing the anthropomorphism he's trying to defend.

Without experience with primates, one could imagine that a grinning rhesus monkey must be delighted, or that a chimpanzee running toward another with loud grunts must be in an aggressive mood. But primatologists know from many hours of observation that rhesus monkeys bare their teeth when intimidated, and that chimpanzees often grunt when they meet and embrace. ... A careful observer may thus arrive at an informed anthropomorphism that is at odds with extrapolations from human behavior.

— Frans de Waal, Are We in Anthropodenial?, Discover Magazine

Although anthropomorphism (at least for some animals) is probably more than a mere metaphor, it is also not a license to assume that people and animals can be automatically equated on all fronts. Instead, the parallels should be leveraged carefully:

We should use the fact that we are similar to animals to develop ideas we can test. For example, after observing a group of chimpanzees at length, we begin to suspect that some individuals are attempting to deceive others--by giving false alarms to distract unwanted attention from the theft of food or from forbidden sexual activity. Once we frame the observation in such terms, we can devise testable predictions. We can figure out just what it would take to demonstrate deception on the part of chimpanzees. In this way, a speculation is turned into a challenge.

— Ibid.

I don't know if all this justifies saying that GPT-5 or Claude Opus or Grok have any form of "ethics, will to survive, or fear," as halvar.flake abhors. It's very nice when a blog post brings up a thorny question and shines light on it until an answer becomes apparent on its own. It's the ideal form that I strive for. The failure of the teleology debate in biology makes me shy away from attempting that here, though.

I will only risk one prediction: the "Should we say that (today's) AI thinks?" debate isn't going to be resolved anytime soon, either.

That said, some people speak with great confidence about things they can't possibly understand—things that even the top experts in the field are clumsily and frantically grappling with. These people are adamant that "predicting the next word"—what LLMs do—is clearly, categorically different from what the human brain does when we say it is thinking. For instance, another one of the thread's commenters writes, without explanation, that "a machine that can imitate the products of thought is not the same as thinking."

(I know, it's internet forums we're talking about. I shouldn't expect much better by default, but I find it strange to ignore such views only for that reason.)

Interestingly, the same person concludes their comment with "LLMs are not intelligence but its fine that we use that word to describe them." But why is it? The differences between a transformer and a brain are enormous, true, but they are based on similar network principles and have many things in common, too. Do you really know how to draw the line, where the family resemblance ends? ●

Cover image:

Photo by Sebastian Hages, Unsplash