A Fundamental Framing of Human Language

The very use of words implies a certain way to segment the world

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo of a platypus in water, by Michael Jerrard, Unsplash

If a framing is a choice of boundaries, and we're forced to pick one in order to build our mental models, what do we usually choose? I don't think we have a full, satisfactory answer from science. Finding a complete answer would require some method of probing people's thoughts, of studying the way we actually—not allegedly—make things click and interact in our heads as we prophesy external phenomena. We're getting there. We aren't quite there yet.

But there is one low hanging fruit we can talk about, one that happens conveniently outside our skulls where everyone can observe it. That fruit is language. Words are how we transmit thoughts to other people, and as such they must reflect one framing or another. So what framings can we spot in the oceans of words we exchange?

Granted, language has no hard limits in length and it's infinitely extensible. Any framing could, in theory, be represented in language. Language is also the only way we can teach each other novel framings, original ways to draw boundaries on the seamless mesh of interactions that we call the Universe. But language seems to be rooted on a fixed, fundamental framing that we all accept. It would be great if it didn't, if it were fully malleable to its very core, but I doubt that's possible. That language should employ a fixed framing at its base is a technical constraint. After realizing that, we can further refine our previous question: what framing are we absolutely, unavoidably forced to use when we use a word-based language?

We could call the answer to that the "Fundamental Framing of Human Language".

For starters, languages—all languages of all cultures past and present—make an assumption: systems consisting of material aggregates that feature sharp interfaces with the surrounding fluid (air, water) are black boxes. Any spoken mental model has to use those objects as building blocks. Those systems get assigned a category of words that we call concrete nouns.

Like all choices of boundaries, this one is arbitrary. It's true that within that material surface—the skin of a mammal, the smooth surface of a rock—the interactions are especially tight-knit and correlated, so that the sub-parts usually move together as a single block. However, those "objects" have roughly the same amount of interactions with the rest of the universe as they do within.

A trillion trillion air molecules pound on your skin every second, electromagnetic waves heat the pebble, other "objects" push and pull and chip away at the interface without end.

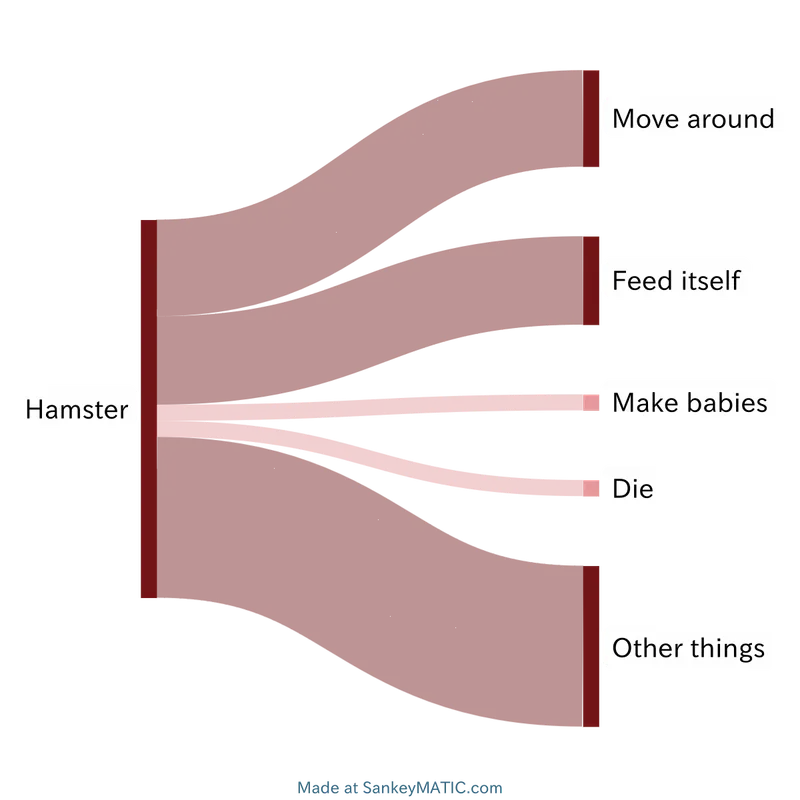

Assigning the static label "hamster" to a furry group of atoms isn't as obvious a choice as we tend to think. A sentient being with a very different kind of intelligence, with a language fundamentally unlike ours, may not see any reason to assign labels the way we assign nouns to "things".

The moment you use a noun to refer to an object, you commit to simulating a world where objects are the preferred building blocks—the black boxes.

What about all those nouns that don't refer to physical, tangible things? How do words like literature, birth, and Canada fit into this framing? Here, I think, language employs another one of its sleight of hand tricks. When we observe phenomena that just won't fit into a physical vessel, we pretend like an invisible, fuzzy, spread-out vessel exists anyway.

So the process is reversed. With physical objects, we usually start by noting their tangible boundaries and then try to figure out what they can do, i.e. what their Trees of Possibilities look like. With abstract objects, we start with the Tree of Possibilities, and we make up a "virtual object" that we can conveniently refer to with a word.

Here the Tree of Possibilities defines the object, rather than being observed in it.

The virtual object we call Canada doesn't exist in reality: it's a pawn we invent in our language to succinctly refer to a bunch of correlated physical objects like territories, accents, and passports, and to lots of other virtual objects like laws and behaviors. Almost paradoxically, abstraction is the reification of correlation.

Of course, we don't have nearly enough nouns for all the objects we want to label. No two things are exactly the same, so even memorizing a billion nouns wouldn't be enough to convey the variety around us. So we have another category of words, called adjectives, that we use to qualify the nouns, to show how a specific object deviates from the average.

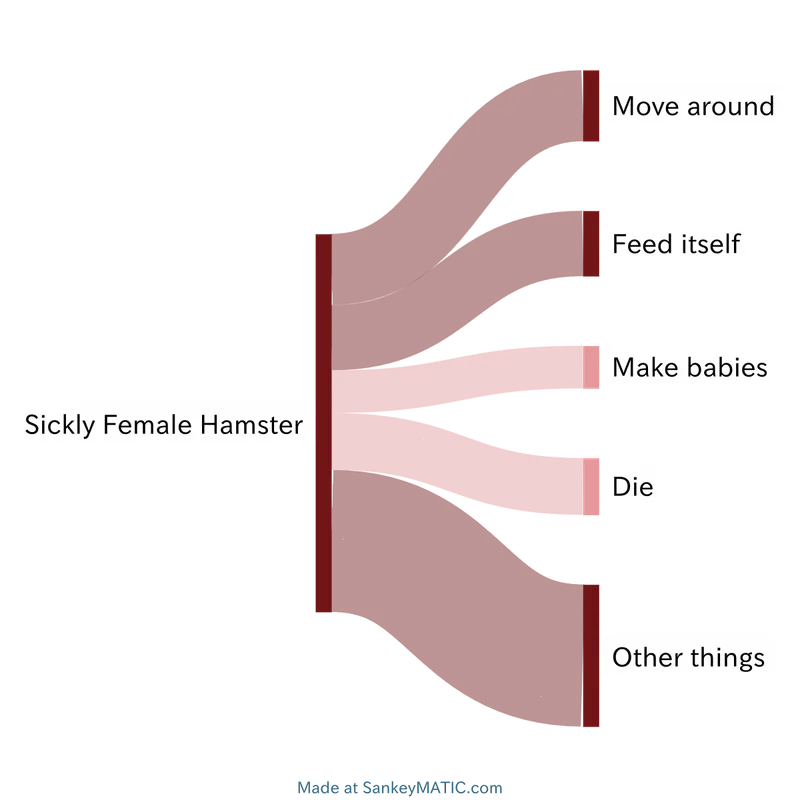

Put differently, using language means remembering a long but manageable list of fixed archetypes (nouns), then patching those archetypes up with caveats (adjectives) until we get to a passable approximation of reality. It's a kind of "perturbation theory" of language.

Perturbation theory is a mathematical technique used in many fields of science. For example, celestial mechanics. The Kepler orbits we study in high school, with their neat ellipses, are a solved problem. We have a perfect equation that describes them without error. Except, Kepler's equation only applies to the ideal case when you have exactly two point-like celestial objects. As soon as you begin considering more realistic conditions, the equation fails. Not a single one of the objects of the solar system traces precise ellipses. They just resemble ellipses at a distance.

To better predict these less-than-ideal quasi-Keplerian orbits, we can use perturbation theory. Its principle is very simple. You start with the easy, exact equation of the ideal case, then add within them new small terms ("perturbations") that account for a rough approximation of a previously-ignored factor. For example, you begin with the idealized solution for the orbits of Earth and Moon, then you add a small and rough term for their non-spherical shapes, then one for the gravity of the Sun, then more for the other planets, and so on.

In this sense, the Fundamental Framing of Human Language uses its own version of perturbation theory to approximate reality. To speak with each other, we postulate "perfect" archetypes like platypus, prow, and stream—each carrying with it a default Tree of Possibilities—then we apply "small and rough" perturbations to indicate deviations from that archetype: the platypus is excited, the prow is wooden, the stream is cold.

If nouns, with the help of adjectives, define the units of interaction for our shared mental models, verbs can indicate the outcomes of those interactions. Dynamic verbs—those that involve action and change, rather than state—answer the question, what outcome of the Tree of Possibility actually materialized?

When I say "the platypus snarled", I'm selecting one of the many branches in the Tree of Possibilities attached to the noun platypus.

The platypus could have also jumped, swam, dived, hunted, foraged, burrowed, dug, waddled, climbed, groomed, died, and more. But in this case, I'm telling you that it snarled. This has an effect on your mental simulation, because you know the verb "snarl" and you know the kind of transformation the "platypus" system has gone through. It's not just a generic platypus: it's a platypus that has snarled. You can update your mental Tree of Possibilities for it, and your ability to predict its next actions increases a little.

There would be something to say about other types of verbs, about adverbs, and all the other elements of a language, but I'm going to gloss over them. I won't attempt a full theory of language beyond this point. We're just taking the "framings = choices of boundaries" framing for a ride, to see where it might lead us.

I'm also not trying to make statements about how this Fundamental Framing of Human Language depends on and affects the way we think. That is a very interesting topic for another time.

But I think we already have enough interesting, if crude, tools to attempt some observations about the failure modes of language, so here it goes.

First, concrete nouns are a pact with the devil. With nouns, we gain the extreme convenience of indicating things quickly with a couple movements of our lips or fingers, and they work fine 99% of the time. In exchange for that, the remaining 1% of times is incredibly confusing for us.

When your partner dumps you saying "I feel that we're not compatible", if that baffles you it's not because such a statement is impossible. It baffles you because you've been treating them as a stand-alone, autonomous system with a boundary coinciding with their skin, instead of the open system of far-reaching interrelations and feedback loops that they are.

Confusing the boundaries prescribed by a concrete noun with the actual target of your emotions cursed you with a huge blind spot. The Tree of Possibilities you want to simulate depends on much more than that physical being you can touch and smell (hint: it also depends on your own actions).

Second, abstract nouns exist only in our heads, but language treats them as equivalent with physical things. It's only natural that this leads to more confusion. We use abstract concepts to more conveniently explain processes and correlations, but we often fall into the trap of thinking that there is actually something out there that does those things. There isn't. Sorry, Canada.

This is why arguing over the definition of "life" in abortion debates, "marriage" in same-sex marriage debates, "art", "justice", and so on are a waste of breath. When you get far enough from the original context, the important phenomena and their correlations change, so you can't expect the original word to keep making sense.

Even in the case of adjectives, the third category I mentioned above, the limits are easy to spot. In any field it is applied, perturbation theory fails as soon as the perturbation stops being "small and rough".

If you want to predict the trajectory of a satellite as it re-enters the Earth's atmosphere, you can't treat air drag as an approximated perturbation on top of a perfect elliptical orbit. You need the full, detailed equations describing air drag, and solve them the hard way alongside the effects of gravity. Similarly, no amount of adjectives will properly convey to you what a naked mole rat might do unless you observe it yourself for a while. We say that a picture (better still, a documentary) is worth more than a thousand words for a reason.

Besides, perturbation theory also breaks down in chaotic systems. When the outcomes are highly sensitive to initial conditions, even a tiny perturbation would need to be highly accurate to be of use. Since we live surrounded by chaos, adjectives often turn out to be sorely insufficient.

Fourth and last on my rough list are (dynamic) verbs. On the one hand, their dynamic nature means that they're probably the most "realistic" aspect of language, because the universe never stays still: if everything is changing all the time, transformative verbs are more meaningful than static nouns.

On the other hand, verbs have to co-exist with nouns and play by their rules. The risk is that a verb attributes too much causal power to its arbitrarily-bounded subject, ignoring all the tangled external causes spread wide around it.

If I only tell you that the parliament passed a horrible law, by default you're forced to assume that the passing of the law is all the parliament's fault, which it almost certainly isn't. My language is hiding things from you. The burden is on you to remember that there are many other factors at play, like the pressure from voters and lobbyists, existing issues, and whatnot. The language doesn't support the conveyance of such nuances in one sentence.

I find that these hand-wavy interpretations for nouns, adjectives, and verbs more or less match the problems we actually have with language. But if this exercise at reframing language seems too ambitious, it's because it probably is. Please don't take it too seriously. It may fall apart in certain applications, and I didn't even back it up with solid empirical evidence. To the extent that it might produce a few true statements, none of them are especially new.

The point is not to provide a novel understanding of language, but to show that the mere use of a language, any language, comes with batteries included and hard-wired, whether we like it or not. The real "Fundamental Framing of Human Language" might be more sophisticated, more complex, or very different from the one I proposed above, but some framing must be there, because of the very nature of human language. That realization alone, I think, is worth something. ●

Cover image:

Photo of a platypus in water, by Michael Jerrard, Unsplash