An Aphantasic's Observations on the Imagination of Shapes

Log entry of a scientific test subject

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Jadon Barnes, Unsplash

This post is part of the List of Introspective Descriptions.

Premise: I have aphantasia, and I've been participating in fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) experiments at a local university for a couple of years. This allows the researchers to record the specific activation patterns in people's brains, and to train AI models to re-convert them back into images.

Log: A March Afternoon, 2025

I had another fMRI experiment with Dr. O today, the type where I hear the name of a geometrical shape in my earphones, then "picture" it on an empty square canvas shown to me on a monitor. I was shown a set of nine shapes before the procedure started, but during the experiment the canvas is empty. I'm supposed to make it materialize in my inner eye, replicating as closely as possible the shapes I saw before.

Of course, because of my aphantasia, I can't really "picture" anything. Studying what my brain does and doesn't do when I try is the whole point of this research.

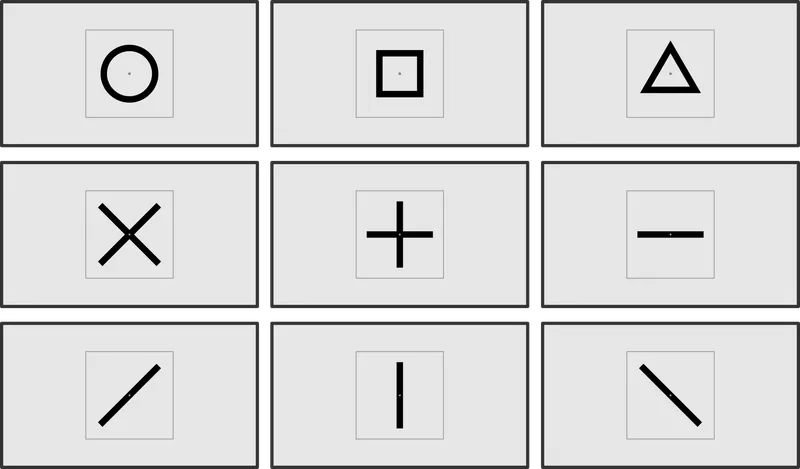

The shapes are:

During the experiment, the screen is empty. It looks like this:

First, I hear the name of a shape ("circle," "45-degree line," "cross," etc.), then I'm given a few seconds to make the magic happen: I stare at the little dot in the middle and project the corresponding shape onto the canvas with my imagination—that is, I try. Like in the six or so previous sessions of this experiment, I had to do a full (randomized) 9-shape cycle twelve times. Since each cycle takes a little over three minutes, the whole thing lasted a little less than one hour.

The first few times I did this, I needed to focus intensely. From the very start, I could confirm once more that my inner eye doesn't work: I see no shapes at all. But I could still "pretend" that the shapes were there, that perhaps they were about to appear in certain predefined regions of the canvas, so that's what I've been doing during these several hours of non-picturing inside the fMRI machine. Although I could never really "see" anything mentally (or perhaps because of that), I had to struggle to keep my mind from wandering, which would invalidate the whole experiment.

With time, though, I've grown accustomed to this task enough to be able to do it without special strain on my concentration. "Pretending" there is a specific invisible shape in a given part of my field of vision has become almost automatic for me, and this has freed up some of my attention to notice the finer details of my experience. That is what I'll describe below.

Invisible Halos

According to Dr. O, my brain data while doing this task shows some slight predictability (this is still unpublished research). His specially trained artificial neural network creates image representations of what I'm supposedly "picturing," and these images do have a rough resemblance to the actual shapes I am supposed to be imagining. So, when the vocal prompt is to imagine a vertical line, the neural network outputs an image that resembles an "I" shape, only much more... bulbous and riddled with artifacts. The resemblance is weaker or absent for more complex shapes like the square, but even in those cases, the generated image is clearly different from a simple straight line.

In other words, in theory Dr. O could pull off a true—if slightly low-key—mind-reading exercise with me: I imagine one of those nine shapes without telling him what it is and, with the aid of his electronic brain, he would be able to guess the correct one with an imperfect but significantly better-than-chance accuracy. This is very interesting, although it doesn't surprise me very much. It seems to indicate that there are some stable brain activation patterns linked with the idea of each shape, even though those patterns do not create in me a conscious sense of "seeing" with my mind's eye. What are those patterns doing, then?

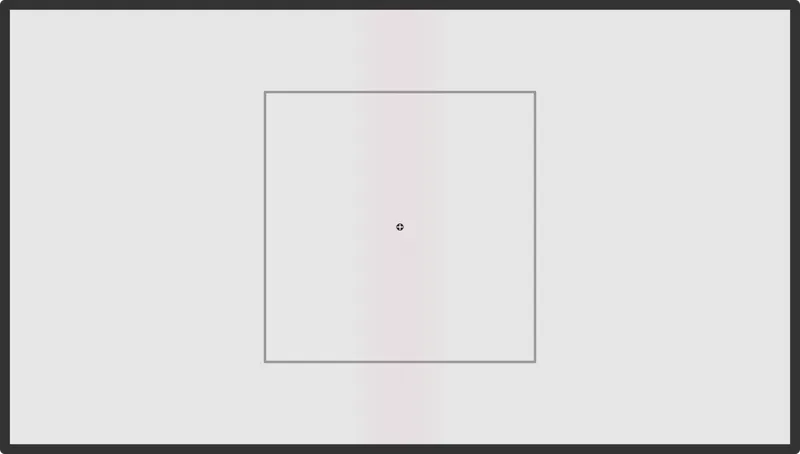

The best way I can express what happens subjectively when I try to project a shape onto an empty canvas is "halos of attention." I don't see anything, in any common sense of the word—there are no contours, no filling, no colors, or connected patterns in my field of view—but I know that certain parts of the canvas are more important than others at any given time, and that can feel similar to seeing. It's as if those regions of the canvas are more "active," more alive than the others.

If I'm trying to imagine an "I" shape in the middle of the canvas, for example, I can "sense" a vertical channel in my vision that passes through the center. Again, this channel doesn't have boundaries or any kind of solidity, but it does have something resembling a basic shape: it's vertical, i.e. it doesn't extend in the left-right direction.

I call them "halos" to emphasize that they are fuzzy and in some way intangible, but that term might still lead people to think about the sight of "objects" in the traditional sense, whether illusory or not. It doesn't feel like that. If anything, they are the lack of something—voids waiting to be filled. Another way to describe them would be as "layer masks," like those that can be created in photo-editing programs to apply visual effects to certain parts of an image with the desired shapes. The masks themselves are invisible; it's the effect that you add through them that becomes visible.

When I try to imagine a vertical line segment, the vertical "channel" I "sense" is not a finite segment but seems to stretch vertically without end. I have tried many times to limit its length so that it fits inside the square canvas, like the sample image, but I couldn't do it. The channel runs all the way off the canvas, cutting through my entire field of vision vertically. It's as if the "layer mask" comes in a preset shape that I can't modify—an archetype for all vertical lines rather than the representation of a specific line of a given length or width.

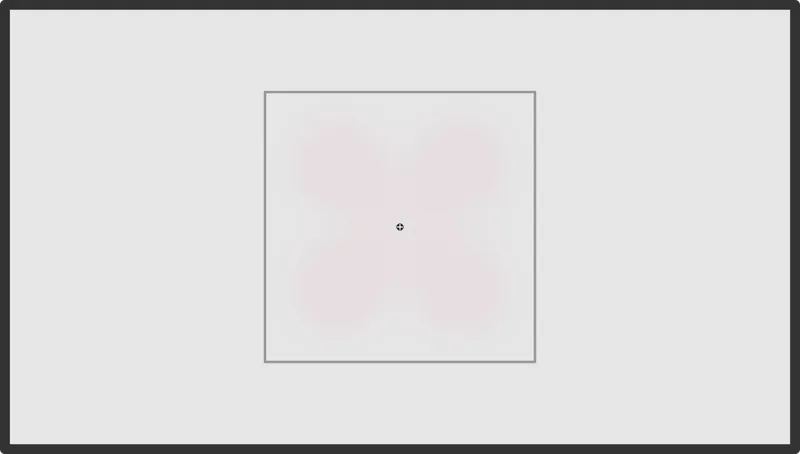

The same halo/layer mask phenomenon happens to me for horizontal and diagonal lines, although the diagonal ones seem to be fainter and do not appear to extend indefinitely like the up-down and left-right ones. For other shapes, I'm able to conjure roughly globular masks within the boundaries of the canvas, but they are vaguer and "disjointed." By this, I mean that they don't form the shapes I want them to form but create separate masks around the salient features of each shape. For example, when I try to picture a triangle, I can form a mask with three very faint globular halos where the angles should be. For the X shape, I see four such halos. In other words, those masks only track the angles and tips of the shapes, not the lines connecting them.

For some reason, the square shape is the hardest for me to "sense" on the canvas. It ends up as a vague blob at the center, almost indistinguishable from the blob of the circle, no matter how much I strive to add four angles to it. I find it strange that it doesn't resemble the halos of the X shape, which should be positioned roughly in the same parts of the canvas.

What Even Is a Mental Image?

Many scientific experiments have shown that people can "prime" their minds and eyes to spot certain things more quickly. This is sometimes called selective attention and works by focusing on specific visual features before they actually appear in front of your eyes: if you crouch over a lawn with the intention of finding four-leaf clovers, you're more likely to find four-leaf clovers than if you crouched to look at the grass without any goal in mind. I wonder if this is what's happening when I try to imagine a shape appearing on a blank slate. I might be creating "slots" for the desired shapes to appear in.

I'm sure this description of my experience will leave some people unsatisfied. It really sounds like I'm seeing something in my mind, after all. Whether I call it a halo or a layer mask, I'm forced to use visual metaphors. Probably my drawings above don't help to dispel that suspicion, since they're (barely) visible.

Am I really aphantasic, then? Or am I, perhaps, hypophantasic, meaning that my mental imagery is faint but not totally absent?

Well, I can't tell for sure without taking one of the objective tests that some researchers have demonstrated, but none of them have been standardized for clinical diagnoses yet. Still, I think I have good reasons to believe I truly have total aphantasia.

I wrote that I "sense" channels and blobs located on the canvas, and that these seem to be more active and alive compared to the background. These are localized differences in specific parts of my visual field, so someone could argue that they count as "seeing mentally" under some definitions. But the real question is whether these are mental images in the scientific sense or not. Here is why I don't think they are.

First, these differences in my visual experience are extremely faint—barely noticeable when I concentrate for a long time on a completely empty and flat gray surface and all but invisible in any real-life situation. In fact, they are so dim that it took me several cumulative hours of focused staring during these experiments to even notice that those halos exist at all! If this is hypophantasia, it's indistinguishable from aphantasia in any situation outside the lab.

Second, these halos only work for the simplest of shapes, like circles and lines, and quickly become fainter and more muddled when attempted for slightly more complex shapes like triangles and squares. There is no way I can create meaningful pictures, like people or buildings, with this approach.

Third, although they do seem to roughly reflect the shapes I'm trying to imagine, they are almost impossible for me to manipulate mentally. I can't make the lines shorter or rotate the triangles at will. They're a bit like non-lucid dreams, where my mind creates all the events, but I can't consciously control them.

Fourth, and most telling, is the fact that all these halos or masks instantly disappear the moment I shift my gaze even slightly. During the experiments, I'm required to always stare straight at a little dot target at the center of the canvas, so that my field of vision is fixed and my neural activation patterns can be compared from one set of fMRI recordings to the next. Rarely, however, I distractedly shift my eyes away from the target for a fraction of a second. In these cases, the halos vanish and take a few seconds to reappear after I've realigned my line of sight with the target.

What does that mean? Again, I can't know for sure, but to me this is a strong indication that the halos are artifacts of the neural networks in my brain tasked with interpreting what I see, rather than direct inner representations of concepts. I believe I'm experiencing something akin to pareidolia, the natural human tendency to see faces and objects in places where they really aren't. Pareidolia is what happens when you see a face in a natural rock formation, an animal in a cloud, or a monster in a Rorschach (inkblot) test. When you expect to see something—either consciously or unconsciously—you might end up seeing it even when it isn't there, a false positive connecting dots that shouldn't really be connected.

However, pareidolia needs some substrate to work on, like a rock with a complex shape. In my case, although the halos appear while looking at a blank gray area of the screen, my field of view is not empty or static at all. Everyone first notices this as a child: when you're staring at a featureless space, whether it be the underside of your closed eyelids, the complete darkness of a cave, or simply a cloudless sky, all sorts of hazy shapes seem to spring to life all over your field of vision—little moving lights, shifting shapes like drapes or tiny lava-lamp blobs, and so on. These, of course, are not objects flying in front of your eyes but rather objects and noise on and inside them.

There are many kinds of these visual phenomena known to science, like afterimages, closed-eye hallucinations, phosphenes, floaters, and blue-field entoptic phenomena. Within certain limits, all of these visual artifacts are normal and always present in humans, but they usually go unnoticed in most daily-life situations because of how faint they are. Some of these are caused by noise or glitches in the neural processes associated with vision, but they are not mental images.

There you go. The halos I described are just as faint and ephemeral as that visual noise. In fact, it feels like they are made of the same substance.

Here is my current best guess for what those halos or layer masks are: they are pareidolia or "wishful seeing" that arises when I intensely try to see something that isn't there. Instead of the usual rocks and inkblots, this kind of pareidolia would use those evanescent visual artifacts in my eyes to almost convince me that there is indeed something like a line or a circle to be seen there.

If I move my gaze, however, the illusion vanishes, because my visual networks can't keep lying to themselves: there is no line or corner there. Since aphantasia is the inability to form voluntary mental images, it doesn't prevent optical illusions and hallucinations, even, I think, when they are induced by the desire to see specific shapes.

There's an Elephant in this Room

I glossed over an important point in this entry: how was I able to create those drawings I showed above, if I don't see those shapes in my mind?

I'm very confident that those drawings are accurate down to the finer details like the shade of gray and the relative sizes (although I did make the canvas and shapes larger than they really are relative to the monitor, for ease of viewing). What gives me that confidence, given that I can't imagine them visually?

This is a pretty huge question, and I have some hypotheses about it, too. But I need to do some more research and introspection work to sort out my ideas. I'll try to write about this in the future. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Jadon Barnes, Unsplash