Blowing Against the Fog of War

A little about Plankton Valhalla and Aether Mug

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Noah Silliman, Unsplash

As a kid I would sometimes play real-time strategy (RTS) video games with my friends. Each of us took on the role of an army—be it the Roman Empire at war with Carthage or an alien species trying to conquer a planet—and built bases, trained troops, and sent battalions around the territory, hunting for enemy camps. The fact that my friends were also trying to surprise-attack my own military bases made my explorations high-risk and high-stress missions.

I think that, for my friends, the fun was in overpowering and obliterating enemy forces. For me, though, the best part was getting to blow away the "fog of war" as I mapped out the land.

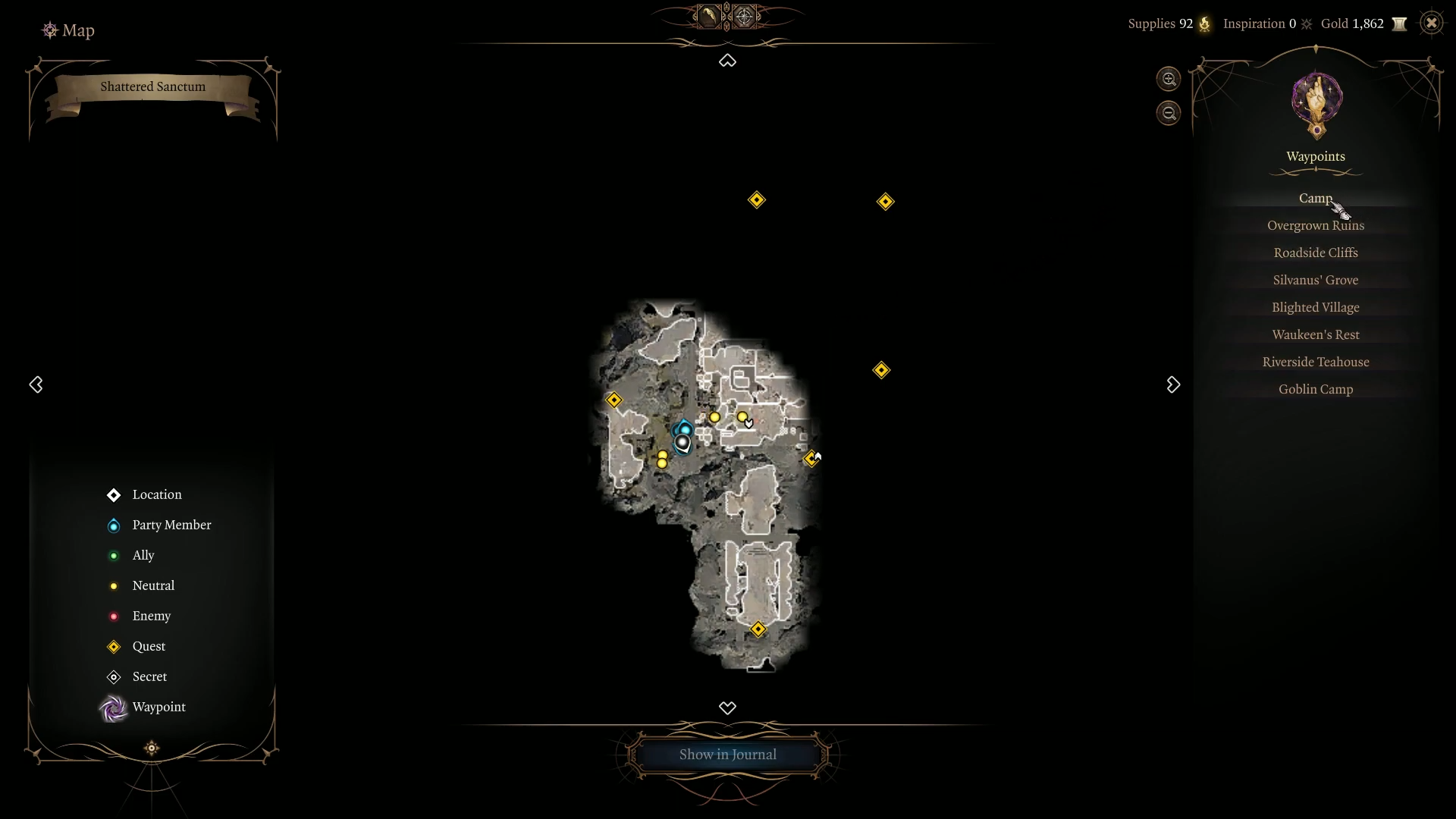

Almost every RTS and exploration game has fog of war. At the beginning of the game, you get a map of the battlefield that is entirely black, except for a little circle of land around your first troops—the only part known to you. As you send scouts and regiments around the hills and the valleys, the places they're able to observe directly get added to the map, replacing the black background.

It's a gross simplification of a real battle situation (thinking about it now, how can the soldiers know so little about the territory? Did they reach their starting position blindfolded?), but it serves its purpose well: it throws you head-first into a sea of uncertainty, and you have to grope your way around, gather your own intelligence.

For a long time I believed the fog of war was something exclusive to video games. It turns out that it is, first and foremost, a military term:

War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.

— Carl von Clausewitz, On War (1832)

There are better and worse metaphors, and there are the delicious ones. The fog of war is in the latter category for me.

I like it not because I have a special interest in wars or video games, but because it works just fine for more or less everything else, too. Replace "life" for "war" in von Clausewitz's quote above, and the remark only gains in depth and significance. We do need a sensitive and discriminating judgment in life, and there aren't many more useful ways of passing our time than "scenting out the truth".

At one level, the scientists are our heroic scouts. We task them with scouring the land, scratching away at the black parts of our map like a giant epistemic scratchcard. Gradually, they reveal the features of the knowledge landscape and expand what we can think and do as a species. They work on what we might call the "Humanity Map", shared by all of us collectively.

At the individual level, though, our progress is much more limited and patchy. Each of us knows only a tiny fraction of the cumulative human know-how. Any person's map is distinct and—compared to the Humanity Map—almost entirely covered with thick fog of war. A scientist's work won't help you unless you go and study their work in depth, copying the newly-mapped landscape to your own "Me Map". And no matter how much time you spend on that, you won't be able to do it for all scientists that have ever lived. Your brain is a battalion of one.

This is something that has always bothered me. I want to see the whole map! I want all of us to see it all! That wouldn't only be very interesting to see, but it would endow us with superpowers, because the map we're talking about shows the workings of reality itself.

I thought about how to achieve that. Eliminating the "fog of life" entirely is not feasible for obvious reasons, but can we at least do much better than now?

The easy answer is that we can do better by improving education. Teach more stuff and more meaningful stuff to more people—have children copy more of the Humanity Map into their own Me Maps. As much as I agree with that, I've found that it's roughly as easy to pull off as clearing an Earth-sized scratchcard with a toothpick. Everyone's time and brainpower is still limited, and it's not like no one ever tried before.

My modest (but still super ambitious) answer is to work on the "field of view" of each individual, rather than on the amount of land they explore. If you have a wider epistemic field of view, you clear up more fog of war with each step you take. In less metaphorical terms, I believe we need to increase each human being's power to interpret and understand the world around us. This would increase our Big-Picture View of the world superlinearly (quadratically?), in the same amount of time and effort.

One way to do that is by devising a powerful language that makes it easier to talk about complex things. Its vocabulary should capture the meaningful patterns that we encounter in our lives, but it should be general enough to be applicable in all kinds of situations, for all kinds of people. Its grammar should be simple and its rules of application few, otherwise no one would bother using it. That's all easier said than done, but I wouldn't be attempting it if I didn't think it was possible.

At the collective level, science has given us many good technical languages pertaining to the separate fields. Specialization is great for humanity as a whole, because we have lots of people specializing in different things. But if you want to fight the individual-level fog of life, specialization doesn't help. You need some amount of scientific generalism.

Fortunately, we're beginning to develop strange new ways to study the world that transcend the specifics of any field of science, being applicable to just about anything.

Fragments of these universal insights come out of niche-sounding fields like network theory, game theory, dynamical systems theory and cybernetics, others from the more mainstream theories of evolution, behavioral psychology, and economics. You get hints from books on "antifragility" and "ergodicity". Even computer science, which might sound like a very specialized field, has some powerful generalist language. Systems theory and complexity theory are two broader umbrella or "connector" fields for this stuff (this kind of science is inherently about making connections between disparate areas).

Those researchers are thinking hard about wacky-sounding stuff like molecular computation, the Darwinian evolution of ideas, the similarities between lightnings and bacterial growth, and the fluid dynamics of crowds and ant colonies. Wacky they are not, though—at least not wackier than the kinds of situations we all meet every day, like chaotic households, political workplaces, group-think media, and collapsing ecosystems.

Knowing the structure of an atom, the curvature of the Universe, or how to make blue LEDs is useful to humankind as a whole: it's good new territory uncovered on the Humanity Map, and we know how to put them to good use sooner or later. But for the fog on your personal Me Map, understanding liquid crowds and adaptive ideas is more useful, because it trains you to spot connections and form better models of everything you see.

The only problem is that those "generalist" fields are still highly technical. The language used today to talk about those topics is too specialized for the average person. Applying general rules to concrete problems still requires some understanding of fundamental natural processes that can be hard to visualize. The tools we have to work on them, like the mathematics of dynamical systems and nonlinear differential equations, can be hard to swallow for the non-scientists among us. Despite all that, I'm convinced the important bits can be made easy enough for everyone.

That's my project with Plankton Valhalla and, to some extent, with this blog—Aether Mug. I'm trying to craft a user-friendly mental toolkit that any non-expert can learn in a breeze. This language could then be used every day, as casually as we talk about the weather, sports, and politics—and indeed used to talk about all those familiar things. I think it would have the potential to deepen the popular discourse, squash at least the most blatant mental biases, and loosen the grip that short-sighted faction ideology has on us.

Plankton is a toolkit to understand the physical world with the generalist-science lens. Aether contains, among other things, framings about framings for building that toolkit. Both are works in progress, and both are very difficult and very fun to write, requiring constant sorties into the black parts of my own Me Map. I hope they'll help blow away the darkness for some readers, too. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Noah Silliman, Unsplash