I Used to Know How to Write in Japanese

Somehow, though, I can still read it

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

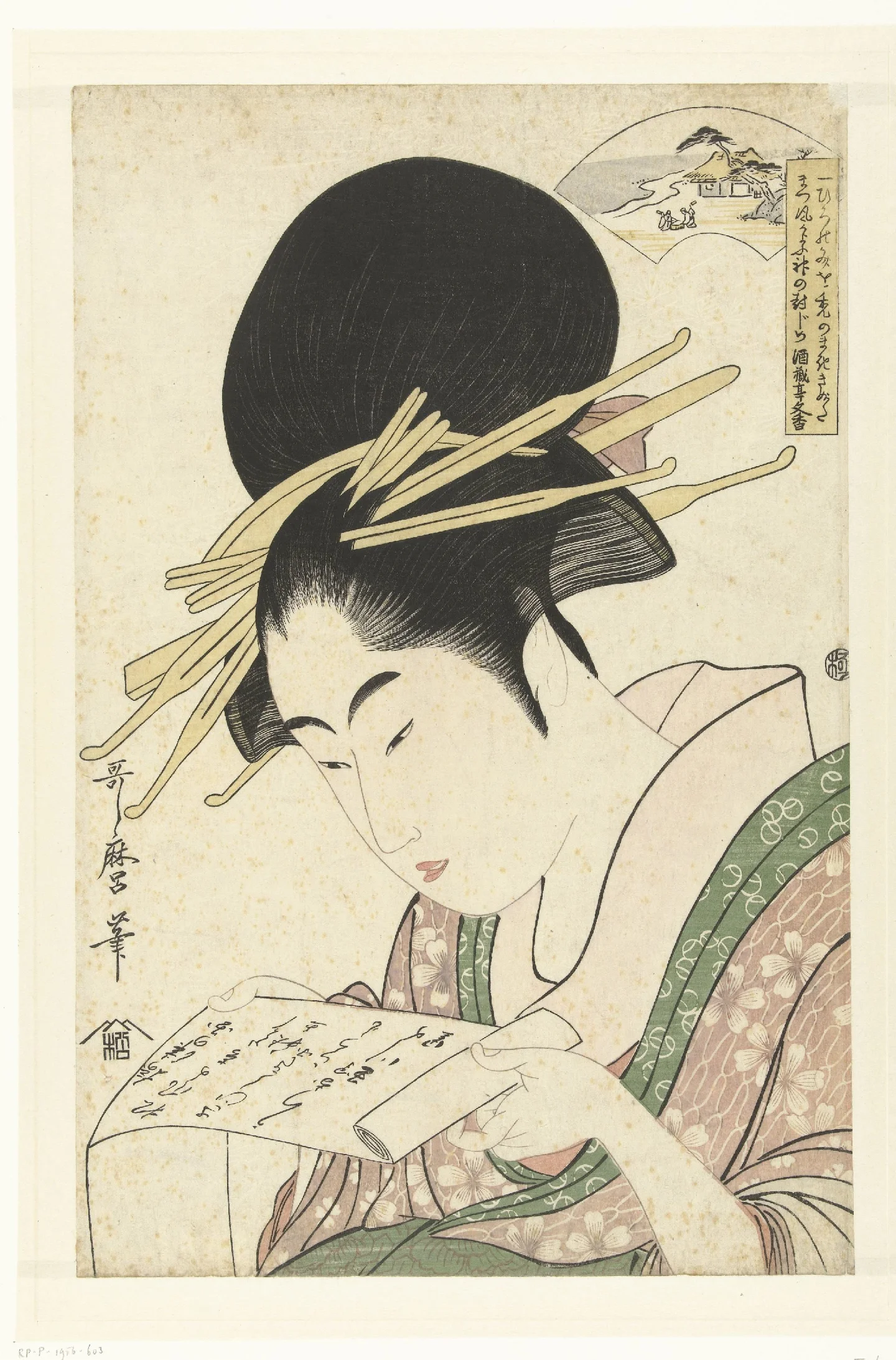

Cover image:

Kazuenokami Katō Kiyomasa Observing a Monkey with a Writing Brush, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

I recently came across a short essay about kanji—Japanese logographic characters—by a certain James W. Heisig. His point is that learning kanji presents two obstacles: remembering what the shapes mean and remembering how they are pronounced. And it is a bad idea, claims Heisig, to try learning both at the same time. Japanese children learn the spoken language first, then they learn how to write it in elementary school; Chinese students of Japanese (who tend to be pretty good at it) have pre-existing knowledge of character meanings and forms from their mother tongue, so they only have to learn how to pronounce them. Therefore, a Western learner should first focus only on the meaning and writing of those couple of thousand common characters and, only after having mastered those, should move on to studying the pronunciations. Heisig professes simple divide and conquer.

That sounds plausible, but is it really an effective approach? How can you keep so many of those tangled squiggles in your head without even knowing how to say them out loud?

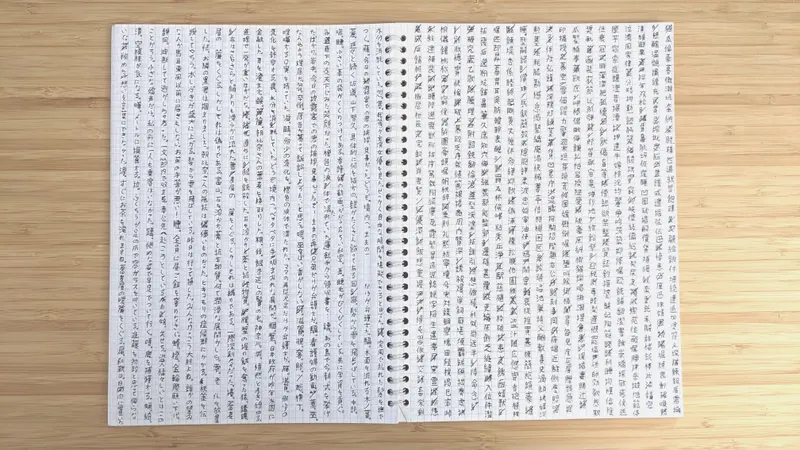

The answer is yes, it works. At least, it worked fantastically well for me. The first thing I did when I began learning the language in 2006 was opening Heisig's famous Remembering the Kanji Volume 1 and going through it, one kanji at a time, using the book's mnemonic techniques to commit to memory the meaning, construction, and stroke order of all 2042 characters in the book. No thought to pronunciations, words, grammar—just the way each character is written and understood. I filled several notebooks with handwritten characters as I practiced recalling them every day, and eleven months later, I had them all in my head. I could write and understand them all with little effort and, from that point on, learning how to pronounce and compose them into words and sentences felt like a breeze. Prof. Heisig has my eternal gratitude.

But fast-forward two decades, and the situation has evolved in an interesting way that I would never have anticipated. I spent over thirteen years in Japan, and my Japanese has only gotten better. My friends and colleagues in this period have been mostly Japanese natives, as is my spouse. I use the language every day at home, I use it to read novels and send emails, to watch South Korean shows with Japanese subtitles, and to file my taxes. I use it more than my own native language, both in spoken and written form. And yet... I cannot handwrite most of those kanji any more.

Except for a few hundred simple and/or frequently recurring characters (like those in my home address), I just cannot recall how to draw them out with a pen. I haven't completely forgotten them, and I'm perfectly capable of reading and understanding them in the blink of an eye—it's just the act of turning the intended character into ink on paper that is often impossible for me.

I'm not alone in this "character amnesia," either. Whenever I tell a Japanese native about my lost ability, they all readily admit to having forgotten how to write many kanji, too. Apparently, this is a well-known phenomenon in Japan and in China. There is even a term for it, wahpro baka (ワープロ馬鹿), meaning "word-processor idiot," from the idea that spending too much time typing into Microsoft Word makes people's handwriting skills atrophy.

Is it only me, or is all of this surprisingly deep and fascinating?

I wrote previously about the beautiful dissociation of the Japanese language, where the way you write and the way you pronounce kanji are two separate worlds with no simple one-to-one correspondence between the two. What this handwriting forgetfulness shows is that there is an even deeper separation between how our brains process the act of reading and that of writing by hand.

Indeed, neuroscience research has shown that reading activates visual-language pathways in the left hemisphere of the brain, from the occipitoparietal to the posterior temporal cortex. Writing kanji, however, is driven by our motor-planning and primary motor cortex, as well as a network in the posterior parietal cortex specialized in remembering the sequence of strokes necessary for the task.

In other words, what feels like a single, monolithic "literacy" ability is actually two distinct skills, each exercised in different instances and each capable of improving and decaying on its own. We all learn two ways to handle text, not one, although we usually learn them at the same time. Spend years typing on a phone with autocomplete, and your pen-focused neural network weakens.

Hold on. This explanation is quite convincing, but it doesn't solve the entire mystery. The thing is, I have aphantasia: I do not have, nor can I choose to conjure, images in my mind. On the surface, this atypical trait seems to explain quite well why I can draw a blank when asked to write the kanji for "plant" (植) from memory. I don't see the character in my mind, so it makes sense that I can't reproduce it on paper.

What confuses me is that other people can form images in their minds. Are all those with character amnesia also aphantasic? That can't be, given that aphantasics amount to less than 5% of the population, while a much larger number of people forget how to write (70% of teenage participants in a Chinese TV show were unable to write the word "toad"!).

How is it possible for you to "see" the text in your mind and not be able to replicate it with a pen? Even if the mental image is faint and fuzzy, surely you can sketch it out roughly at first, then refine it until it settles into its exact form? Apparently, that is not how mental images work, either.

Admittedly, I've never heard of someone forgetting how to write a letter from the Latin alphabet. Character amnesia is mostly a thing with logograph-based languages. The simplicity of letters and the much higher frequency of those symbols probably play a role—you encounter "R" in a text much more often than "plant." I wish there were more research on where exactly the line lies: how complex and how numerous do the symbols in a writing system have to be in order to create a character amnesia problem? The answer sounds important, because it would tell us about some fundamental limits to how the brain processes visual information. According to the Language Closet, researchers "found that character frequency, age of acquisition, spelling regularity, familiarity, stroke count, and imageability were significant predictors of character amnesia," but this result is partial and muddled by other, less relevant factors.

Back to the phantasia paradox: for some reason, mental images don't help significantly with writing. I think this hints at the incredible compression ability of the brain.

There is a widely accepted theory in cognitive science called fuzzy trace theory, which hypothesizes that there are two ways we encode (record) memories in the brain: verbatim traces and gist traces. The verbatim kind is what we typically think of as "good" memory—the ability to remember something in full detail, almost literally. These are relatively precise memories, but they are difficult to retrieve and easy to forget. They're not "sticky".

A gist trace, on the other hand, is the quick and very sticky transcription of only the salient parts of the experience—minus the details. They are the sublimation of sensory information into fuzzier, abstract "meaning"—a form of compression. Gist memories jump back at us more readily and are harder to forget, but they lack all the particulars of verbatim memories. And, crucially, forming gist traces doesn't depend on having verbatim traces.

When you read something, both verbatim and gist traces are recorded in your brain, but the latter leave a stronger and longer-lasting presence. In the case of 雨, your gist trace might simply read "rain / Chinese character made mostly of horizontal lines and drops". The exact (verbatim) shape may not even leave a mark in your mind until you've seen and studied it carefully several times over.

In practice, this means that you don't have a single, complete "source file" for a character or image stored anywhere in your brain. There is the abstract gist of it somewhere, with just enough features to allow you to recognize it when you see it again, but the exact details are nowhere to be found. The details may be scattered in other parts of your brain—for instance, in your motor memory networks, which allow you to write the character down—a different set of neurons that needs its own painstaking training. Reading a complex character, then, means "recognizing the gist," and writing it means "activating your memory of the precise movements needed to reproduce it." Two starkly different tasks.

This distinction applies to much more than East-Asian symbol recognition. In Reading Blood Meridian with Aphantasia, I described my experience reading a notoriously gruesome novel by Cormac McCarthy. I noted how the vivid and atrocious depictions in the book don't provoke the deep, visceral reactions that others talk about.

It feels important but remote, not something related to me personally. Kind of like observing the events from a flying bird's (metaphorical) eyes—more than far enough for objectivity, but keen enough to take it all in.

This sense of remoteness might imply that, due to aphantasia, I only get the gist of the written experience from the text, bypassing the verbatim kind. My image-less reading experience is almost pure abstraction, because there is very little visual verbatim information to be stored in the first place. I have countless powerful "memories" of that novel, but I would never be able to reconstruct even a single intense scene to any degree of fidelity.

This is also why I believe that language is a bottleneck for thought. Most of what you remember is nothing like an approximate copy of the things you experienced in real life—even in the specific case of text, memory is not even remotely like a paraphrase of previously read words. Many of our thoughts happen in a highly abstracted and distilled form, interacting and connecting with each other as a network that simply cannot be faithfully converted into a sequence of words, however long. The fact that people can fail even at something as basic as sketching a kanji or a vehicle they've seen hundreds of times before is just another example of the same phenomenon.

It turns out that the bottleneck is not only between different minds, but also between parts of the same mind. In my case, Prof. Heisig's divide-and-conquer approach worked well to create the perfect scaffolding to learn the Japanese language as a whole. But when the scaffolding was dismantled to reveal the completed structure, the ability to write by hand was thrown away with the rest of the junk. ●

Cover image:

Kazuenokami Katō Kiyomasa Observing a Monkey with a Writing Brush, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi