Case Study: Is There a Strange Culture War Over AI Art?

Studying a thought process

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

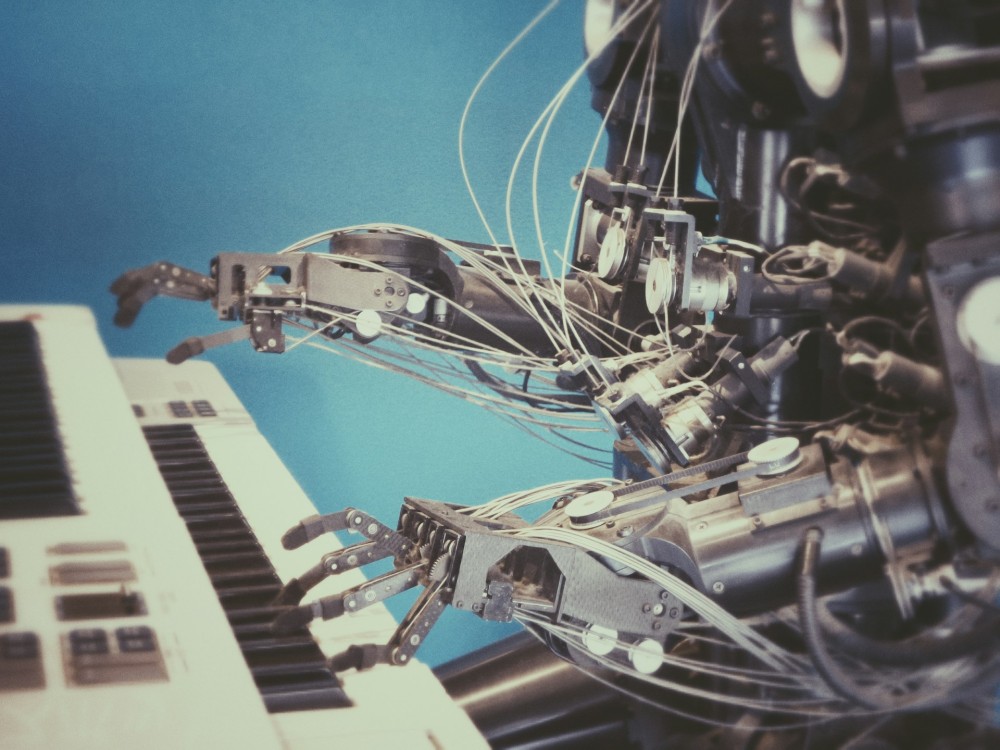

Cover image:

Photo by Processed Photography, Unsplash

I often write about general and abstract concepts and "thinking tools", but I would hate it if people thought they are idle philosophy. Everything I write about is meant to actually help you think a little better, a little clearer—and of course I dogfood all of it. The difficult thing when writing about them, though, is finding simple, non-contrived examples to make these ideas, and their applicability, clear. Here I want to try a different approach: I'll take someone else's argument as a case study. I'll deconstruct its reasoning and show what needs to be done to make it stronger.

For this purpose, I have selected this recent post titled The Strange Culture War Over AI Art by Danny Wardle on the Substack "Plurality of Words". It is a brief disquisition about what the author calls a "culture war" between the proponents of AI-generated art and those who want to ban it.

I hesitated when choosing the subject of this analysis, because I would essentially critique someone's writing in a very strict way, and hurting people or picking fights is the last thing I want. Wardle's post seems like a good choice, though: it's short, its mistakes are not too subtle, it's about a very contemporary topic that I am interested in, and it was written by someone I don't know, living in a distant country whose politics I am not entangled with. I don't have any horse in the race, because I don't identify with "tech bros" or "indie artists"—the two factions that are apparently waging this war against each other. (In fact I identify a little bit with both groups.)

Most important of all, Wardle is a philosopher: if any group of people ever appreciates a stern review of their thought processes, that must be philosophers!

Still, just to be extra-clear, I have nothing against Danny Wardle, nor do I think the post's conclusions are necessarily wrong. I read other posts on Plurality of Words that I found well-reasoned and that helped me see those topics more clearly. Here I am only going to critique the reasoning process laid out in the AI art post—is it sound and convincing or not? Of course, the whole point of bringing it up is that I don't think it is sound or convincing, regardless of whether its conclusions are right or wrong. Showing why is my only goal below.

Before proceeding, I recommend you read Wardle's post in full here: it's short enough to finish in a few minutes. I don't want to misconstrue the arguments therein, so I will assume that you have understood them through direct reading.

I will also use my ideas from these two posts of mine: Rationality Fails at the Edge and A Framing and Model About Framings and Models.

The Claims

First of all, what is the ultimate message of Wardle's post, the point towards which it's trying to build a convincing argument? It's impossible to begin the critique without clarifying this.

The piece's title is "The Strange Culture War Over AI Art", suggesting that it is a description of that culture war, and a demonstration that it is strange and dumb ("one of the dumbest"). In other words, the author seems to be taking an impartial stance, a third-party look from outside the debate, and showing that it is strange indeed. This hunch is corroborated by the first paragraph, with statements about "modern culture wars" and "political polarization". The last paragraph's conciliatory tone seems to support this as well. I will call this the Surface Claim of the post.

There is another claim half-hidden in this post, though, which I'll call the Subsurface Claim. This is not signaled in the title or in the first paragraph, but the author seems to want to show that AI art is fully morally permissible. This is clear from the fact that the post only brings up and attempts to demolish the arguments against AI art, never those in favor of it. In fact, refuting those arguments is all the post does. Even though the author could use the same argument against conservatives ("they traditionally espoused protecting intellectual property rights, but look at them now, happy to ignore the artists' rights"), for some reason I don't care to guess about, the author doesn't do that.

The existence of the Subsurface Claim is a problem for the strength of the argument, because it undermines the stance of the Surface Claim. How can we trust someone as an impartial observer of the strange culture war if they show a strong preference for one side of it?

This self-contradiction weakens the whole argument, but it doesn't invalidate it altogether. Maybe the initial impression was wrong, and the author wants to show, from the inside, that the culture war is strange and dumb because the opposing side is making it so. That approach is perfectly fine, too, although I think it would be more honest (as in, trust-inducing) to make this partiality explicit in the title and introduction.

Weaknesses in the Arguments

There are some important minor weaknesses that I want to mention briefly before getting to the parts I'm most interested in.

First, it is not at all clear to me that this isn't a strawman argument. Are people really making those accusations and claims under scrutiny? Who are those people? Are they a compact group all agreeing with each other? Is it really a debate worthy of being called a "culture war"?

There are no quotes in the text, no concrete references we can check to verify with our own eyes that yes, there is indeed a faction of bigots trying to carpet-ban AI art, and they rely on all of those supposedly-faulty arguments for their activism. The only evidence given takes the following form:

- "A common objection to AI art is..."

- "Another claim is..."

- "The final criticism I'll address, which is perhaps the most common, is that AI art is..."

Perhaps the reader is supposed to be already familiar with these claims, or to seek them out on their own. If so, I guess that's okay. This is a blog post, after all, not an academic paper, so we shouldn't be too picky. Still, this omission doesn't help the argument.

A flaw that seems less forgivable, even for a blog post, is the game-theoretical confusion shown in the first section, titled "Property Is Theft, but Don't Steal My Ideas". It is an attempt to show a contradiction in the views of "progressives", who ostensibly want to simultaneously abolish private property and protect the property rights of artists against AI "theft".

This point is entirely moot, because it compares ideals for a different way to run society (e.g. communism) with demands to follow the current society's rules. It's akin to saying, "anyone advocating for the reduction of private property in a future society must also be in favor of theft now, otherwise they contradict themselves."

It's the difference between proposing to play Game A, and demanding that the usual (different) rules of Game B be followed while playing Game B: there is no contradiction, no strangeness here. Clearly, even if one believes that Game A would be better and more fun, one may still be justified in opposing the introduction of only some very specific rules from Game A into Game B, claiming that such change might break Game B and make it even less fun than it was before.

In most countries—including the US, which I take to be what the author cares about—copyright laws ban human artists from cloning other artists' works, and from making derivative works without the original artist's permission. Is it fair to not require the same laws to be applied to AI artists in this legal context? That's the real question that needs to be debated (and is being debated at length elsewhere): not "is it fair to require those laws in an ideal communist society?"

This mistake invalidates a large portion of the blog post's argument. It doesn't show that AI art is morally acceptable (the Subsurface Claim), nor does it show the opposite: a flawed argument doesn't show anything.

Alright, but why all these logical hiccups from a blogger who seems otherwise reasonable? We come finally to what I believe is the core of this flawed argument—and maybe of most flawed arguments: it is built on a bad framing.

Poor Boundaries Mean Poor Thinking

In my definition of the term, a framing is a choice of boundaries. It's the definition of an ontology, the arbitrary but intentional separation of parts of reality into "black boxes" that exist with certain predictable properties and can be used to simulate the world. It is also the choice of what boundaries not to draw—i.e., what things we take not to exist, at least in the context in which the framing is used.

What framing does Wardle's blog post use? A very simple one. Here is a representative quote from the piece:

The two camps are clearly divided among the two professions they choose to support: the artists or the programmers. Those on the left fear the displacement of their indie artist friends and those on the right relish at the prospect of telling left-leaning artists to ‘learn to code’.

This is a rather extraordinary claim to make, and there are more claims of a similar nature in that short Substack article. (Unfortunately, as we saw above, none of those extraordinary claims is backed up by any evidence beyond the author's word.)

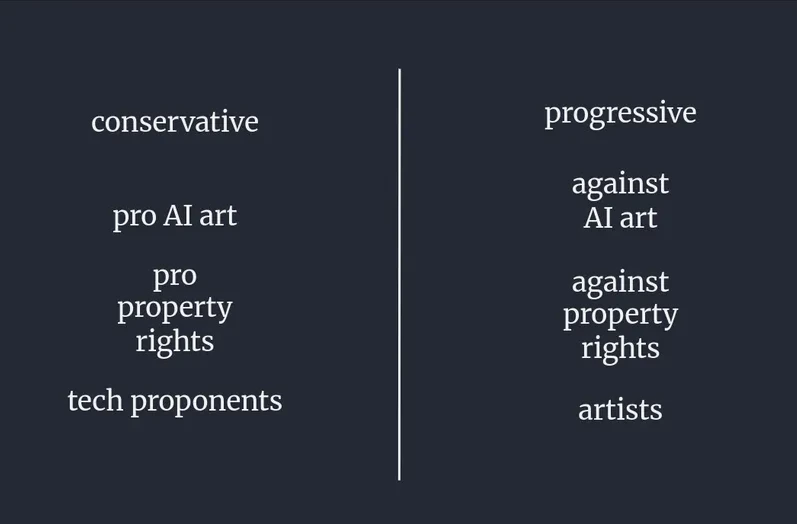

Here is what the framing used by the author looks like, based on the post's text.

Only one line is drawn, and only two black boxes exist in the universe of this post's framing. Because of this, the resulting model of reality is straightforward: two kinds of people disagree on all fronts, so they must make war.

Drawn like this, it looks like an oversimplification, but by how much? In fact, I think it is made up of several false dichotomies:

- A person can be either in the "tech bro" camp or in the "indie artist" camp.

- "Tech bros" are for AI art; "indie artists" are against it.

- Right-wing people are for AI art; left-wing people are against it.

- Progressives in this debate are against private property; conservatives are in favor of it.

- You are either 100% for AI art or 100% against it.

- And so on.

Each of these is false or incomplete on its own terms, but the blog post goes further, making it sound like all of these categories are aligned without contradictions: if you're conservative, you're also pro-AI, pro-property rights, etc.

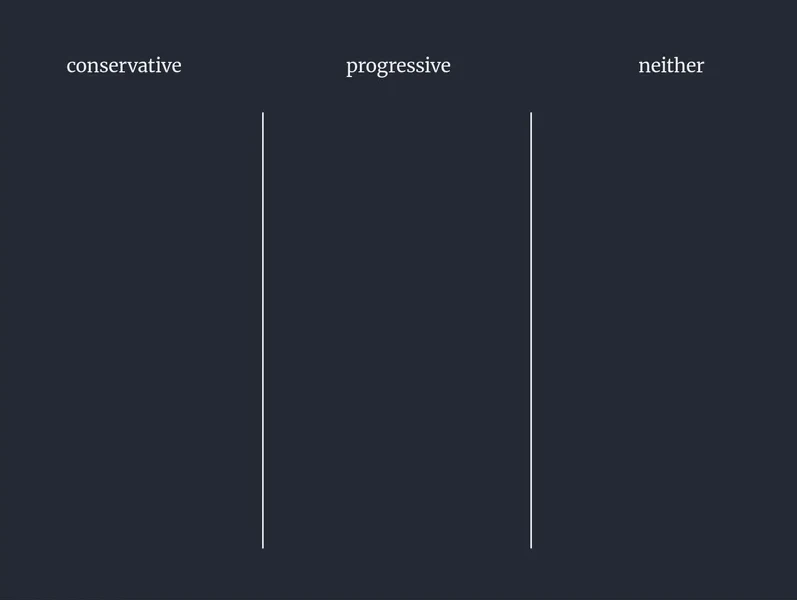

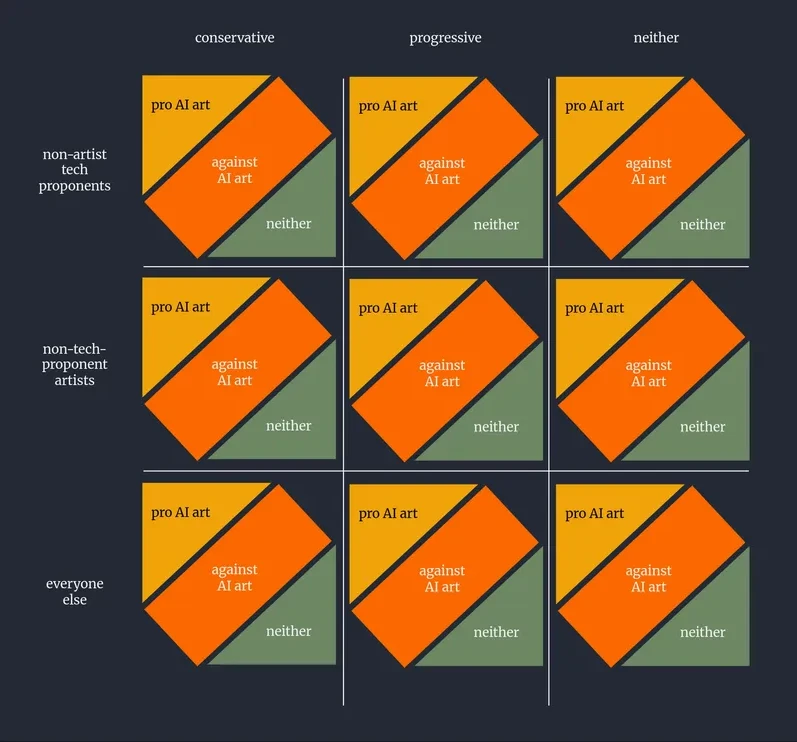

To understand just how reductive this framing is, let's try to make one a bit more nuanced. First of all, let's account for, say, three possibilities on the political spectrum, instead of just two, by drawing a second line.

Still an oversimplification, since I clumped under "neither" all ideologies that can't be defined as fully or traditionally "conservative" or "progressive," but at least this framing acknowledges their existence. Next, we do the same with the question of tech and art (a strange axis to begin with, but we can still use it), and consider all their combinations.

Here I have accounted for something the author of the blog post left out of the framing: there exist people who are both in favor of tech and artists (or are engineers and artists themselves). To omit that category impoverishes the discussion and makes it sound more clear-cut than it really is.

We now have nine categories, from the two we started with. But we're not done, because any of those groups might have one of, say, three opinions regarding AI art. They could be in favor of it, against it, or—if they have no opinion or an in-between opinion—neither.

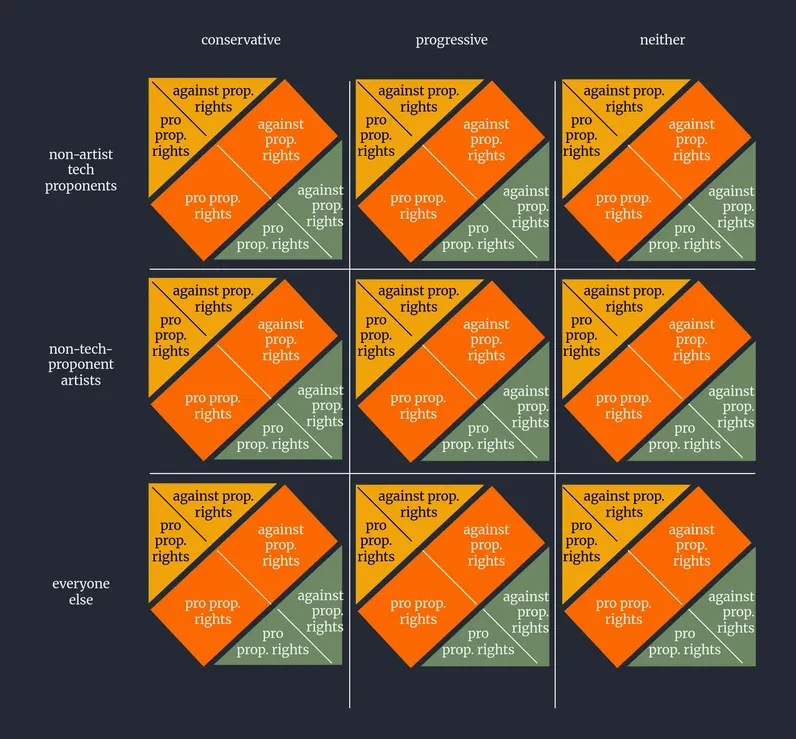

This brings us to 27 groups of people. Of course, some of these groups contain many more people than others, but at least we're not leaving out anyone. Finally, there is one last axis that seems relevant to Wardle's discussion, to account for opinions on property rights.

It is getting so cluttered that I gave in to a dichotomy here just to make things visible (this should really be a 4D table, but I couldn't find a tool that makes those). People in each of those 27 groups can be for or against property rights (or somewhere in between, but you get the idea).

Surely, as the author of the blog post wrote, there are proportionally more people in the "pro property rights" boxes under the "conservative" column than there are in the corresponding boxes under "progressive." But there might still be a significant number in the opposing boxes, not to mention the boxes in all the other combinations in the "neither" column and "everyone else" row.

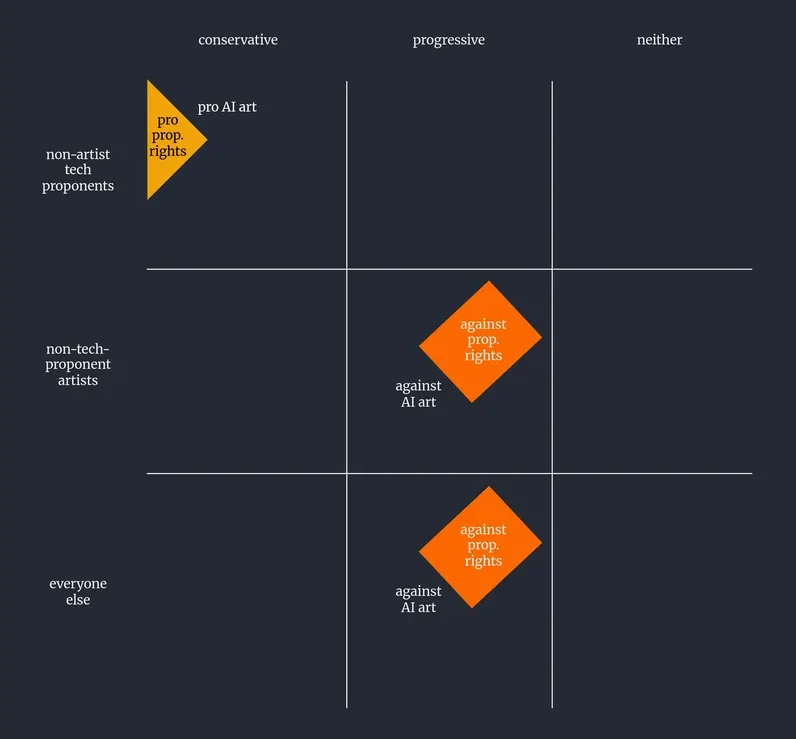

With (at least) 54 groups of people with different positions, there might be so many alternative debates, so many nuances and solutions to consider and pitch against each other. Yet the author writes as if only these existed:

If we use the full picture (the one before this last one), it is evident that any claim that is supported or criticized by an argument needs to be carefully attributed to the right groups of people, and any allegation of contradictions needs to prove that it is indeed a single group of people making both contradicting claims. The author's original two-faction framing, on the other hand, can only lead to seeing things as a simple, and indeed bizarre, "war."

(I will not go in depth on this one, but there is another flawed assumption in this article: that having two ideas that contradict each other somehow invalidates both of them. So, not only did the author claim there is a contradiction where there might not be one, but even assuming the contradiction was real, it would not lead to the conclusion that being against AI art is wrong.)

Asking Good Questions

Rationality fails at the edge, and we've seen that the edge—the foundational framing—in the blog post is not suited to discuss these topics and leads the whole house to crumble. How could the author have avoided this? How to shore up an argument to give the nuance and depth that it deserves?

One method I like to use is to ask myself the good, hard questions. I think a sharp argument should interrogate itself.

Below is a selection of what I think would have made great questions for the author to ask and attempt to answer in the blog post in order to take the conversation beyond all the apparent strangeness. I've already posed several such questions above, so I won't repeat those.

Note that the following might be mistaken for rhetorical questions, that is, a way for me to make an implicit argument of my own thesis while camouflaging them as questions. This is not the case, and I genuinely don't have a clear answer to any of them! Even for those where I do have a hunch one way or the other, my confidence is low, and I wouldn't die on any of those hills yet. I intentionally chose to analyze a blog post on a topic I don't have strong opinions on.

Let's follow the blog post's original structure.

"Property Is Theft, but Don’t Steal My Ideas" Section

This section quotes and seems to fully agree with a blog post by Richard Y. Chappell. The thesis is this: just as an artist has no right to prevent certain groups of people from consuming their art, they have no right to ban AI from training on it. Wardle then mentions the "long history of progressives supporting media piracy on freedom of information grounds," using it to show that there seems to be a contradiction in the stance of anti-AI people (who, remember, are taken to be primarily non-tech leftists).

Here are some possible questions:

- Movie theaters and laws prohibit people from recording movies and redistributing them for free or for a fee: in what ways, if any, does the desire to prohibit AI training on copyrighted art differ? (Any answer to this would be good progress.)

- Would those people still be against AI training if they had guarantees that the trained models would not be used for inference based on their art? (This would show us whether the real problem is the training part or the inference part.)

- Assuming one accepts that AI training on art is moral, does that automatically imply that AI inference mimicking that art is moral, too? (Chappell also leaves this question unanswered, at least in the non-paywalled part of their post.)

- Are the same people who support media piracy also generally against AI art? (The author's binary framing doesn't allow for a question like this.)

- Assuming the answer to the previous question is YES, would those people still be against AI art if their ideals of abolishing property rights, or at least copyright, were realized in society?

"Effort Moralism" Section

Here the author aims to refute another claim of some anti-AI people: that AI art is immoral because it is easy.

Setting aside the doubt of whether people actually make this argument in this manner, another good question could be:

- Are these people criticizing lazy individuals who use AI art for personal use as harshly as they criticize those who use it for personal profit? Do they equally despise the 10-year-old girl who Ghiblifies her friends for fun and the AI artist or company that sells Ghibli-style portraits to rich people? (I think the answers would have a large bearing on how this debate is analyzed and just how strange or dumb it feels.)

"The Slop Heap" Section

Next, we are told that another claim for the immorality of AI art is that it is missing something fundamental: it's inauthentic. I've heard people say that AI artists are lazy and have even seen some attempt to shame AI artists with this argument. But I don't know the answer to this question:

- Do a majority of those against AI art claim that being inauthentic is a key reason to ban it or to consider it immoral?

Since the blog post doesn't ask or answer this question, we don't even know if this section is linked with the rest.

"It’s All Displacement" Concluding Section

The last three paragraphs of the Substack entry attempt to reframe the problem in a more meaningful, less strange light. The author wants to make a parallel between what's going on in the art industry and what Freddie DeBoer wrote in a 2021 blog post about the displacement of the media industry. When Substack arrived, writes DeBoer, there was much backlash from people on "Media Twitter," who claimed the way the platform made and distributed money was harmful to news outlets, journalists, and readers. But the real cause of these issues, we're told, was the failings of the media industry itself. Substack was the solution that would save journalists, giving them financial independence and full control over their own output.

These are some questions that come to mind based on this:

- Given that we have a few years of retrospection available, was DeBoer's assessment of Substack vs. Media fair and accurate?

- If the seismic shift caused by Substack ultimately made journalists' jobs more sustainable, will the even bigger shake of generative AI ultimately save traditional artists from the evils of their own industry? (This would make the parallel explicit and justify bringing it up.)

- How many people are against AI art in absolute moral terms, and how many are against AI art in the context of the current capitalistic forces that seem prone to squashing the already-precarious livelihood of human artists? (An expansion on a question I asked before.)

- Of those who are mainly worried about human artists starving to extinction, how many would still be against AI art if it were effectively regulated so that part of its profits were redirected to the artists, sufficient to make their work sustainable?

- If the implication is instead that traditional artists will (unfortunately) have to go extinct to be replaced by powerful new AI art, this may or may not have a large impact on the production of new, entirely novel, and non-derivative works. Might this prospect be what many people are worried about, instead of universal moral truths? (In my opinion, this is the most important question, worthy of being tackled at the beginning of the post.)

TL;DR

By analyzing "The Strange Culture War Over AI Art," we have seen some ways in which a rational, intelligent person can sometimes undermine their own arguments. More constructively, we have seen some helpful thinking tools in action. Here is a brief roundup.

First, be explicit about what you're really trying to argue for. If you want to be impartial, act impartial. If you want to be partial to one opinion, that is fine as long as you don't try to pass as a neutral observer. Making the reader hunt for "subsurface goals" between the lines doesn't bode well for your chances of convincing them.

Second, always draw 4D tables of your framings remember that you can make the most flawless logical argument possible, but if your basic assumptions are wrong or inadequate, it will all be in vain. To the extent possible, always prove—to yourself and to the reader—that you're jumping off from the solid foundations of a suitable framing.

Third, ask yourself the hardest questions at every step of the process. Don't just write what sounds reasonable: always wonder if there is more to it, seek out the possible objections and gradations, grope in your blind spots.

After all that, some readers might still be wondering what I think about the subject of AI art. I avoided saying anything about it in the text above because it is really beside the point. But it's not like I want to keep it secret. For what it's worth, here is a short version of it.

Is there a debate important and compact enough to merit the term "culture war"? I didn't see any convincing evidence for that, unless you call any instance of "some people arguing on moral matters online" a culture war. That's a pretty low bar. That there is a debate—several debates in parallel—however, I have no doubts.

Is that debate(s) or war strange? Only if you look at it through strange lenses.

And is AI art "morally permissible"? I really don't know yet. I've marveled at it and used it in some cases (you'll find it in some of the early Plankton Valhalla essays), and I have also avoided relying on it too much as a substitute for anything more than personal and private fun. I suspect the answer will not be a yes/no dichotomy. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Processed Photography, Unsplash