Is There Anything Untranslatable?

Words do mean things, but not only.

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

The Godfather, 1972

Last month I wrote a post about some unique quirks of the Japanese language. Afterwards, I had some lovely conversations about it. Most people seemed to agree with the things I wrote—which I'm pleased of—but you know how the brain works. The comments that tickled my curiosity the most were the skeptical ones. One particular point came up a couple of times: was I justified in claiming that some Japanese words and phrases are "untranslatable"?

What an amazing question! I had never thought about it critically, but it has big implications. The answer to that question has a huge impact on the very value of language learning.

My gut reaction was to answer "yes, there are untranslatable words". But why? It's worth breaking that down to see if it makes sense.

But frankly, more than that, it's worth it because it uncovers a lot of delicious aspects of language.

On the Surface, the Argument Against Is Strong

All modern human languages with enough speakers seem to be capable of expressing any concept, however complex, by means of composition, recursion, and simply adding more clarifying words. To repeat the same thing in computer-science-y terms, all major languages are "Turing complete". If that is true—and I believe it is—then there can't be any idea that can be stated in one language but not in another one.

After all, monolingual dictionaries exist for the precise purpose of expressing the meaning of every word without using that word. It follows that, if anyone claims that word X is untranslatable, all you need to do is translate that word's monolingual definition, which usually will be made of translatable words. Hence, every word is translatable.

For the most part, this line of reasoning is convincing, and I agree with the conclusion that any concept can be defined, explained, and understood by speakers of any other language.

Something about that logic nags at me, though, like something was missing.

Language Grafting

If you've ever shared two or more languages with a friend—both of you fluent in those languages—you've probably experienced an odd phenomenon at least once. You're chatting in Language 1 (say, English), but every now and then, almost unconsciously, one of you drops a word of Language 2 (say, Catalan), only to immediately return to English as if nothing had happened.

You're both perfectly comfortably with that, because you understand both languages. But a bystander who overhears your conversation (and doesn't speak Catalan) would be rather put off by that. The insertion of an alien word in the middle of the dialogue feels like a gaping hole to them. They (the bystander) might ask: why not stick to one language, if you both know it?

This language-hopping behavior is called code switching and, in my experience, it's extremely common in multilingual communities. I've caught myself and my friends do it with—depending on the friend—Italian and English, Italian and Japanese, and English and Japanese. In other words, all the language combinations I have access to.

The interesting thing about code switching is that it happens even when both speakers are native in the same language, and using their native tongue as their basis. Why go to the trouble of mixing in a second language then?

In some cases it's a matter of habit, especially when you have some reason to speak the second language every day. You may get so accustomed to it that some words pop up in your mind before the native equivalents.

But often a single, fitting native word simply doesn't exist that works as well as the foreign one in that situation. I often have conversations like this:

Marco: I'm looking for a date spot, have you been to that restaurant before?

Friend: yes, it's great.

M: nice and cozy?

F: yeah, especially very... shibui.

M: perfect, she'll love it then.

Shibui (渋い) means, in this context, quietly refined in an austere way, without pretenses, almost stoic. Saying shibui like that, in a mere second, conveys what would otherwise make a clunky and unnecessarily long digression.

Instead of code switching, we could use a few more words to convey the same meaning. If necessary, we could open an online dictionary and quickly conjure up a clear definition in Language 1. But we don't usually do that. In the blink of an eye, we change language and then change back again, confident that the other will follow.

If we make that choice over and over, there must be a reason.

The Stuff that Is Lost

Douglas Hofstadter, an American cognitive scientist, told the following story during a lecture titled Analogy as the Core of Cognition. It was about a time when he visited an Italian research institute for a year:

And so the question that I had to face from the very beginning was what do you say to these people when you run into them in the corridor and you don't even know quite who they are; [or] you recognize them and you sort of know who they are; [or] you have spoken to them and you know definitely who they are; [or] you know their name or you know them pretty well, they're kind of a friend, you've eaten lunch with them once; or you are a friend?

Naively, being American, I would say "ciao". Ah, that was wrong! You don't say "ciao" to people that you are not on familiar terms with.

I mean, "ciao" is something that you can say to somebody that you say "tu" to, but you don't say "ciao" to the director of the Institute. That just doesn't work. You say "buongiorno", or you say "salve" and "salve" is sort of intermediary.

His broader thesis in the lecture—a fascinating lecture well worth a watch—was that we always think through analogies, and which words you choose in a given context is also a matter of finding "what this situation is like".

In this case, for an American, all those various situations were like "hi" situations, and "hi" is usually translated to "ciao" in Italian. But, during that year as a visiting researcher, Hofstadter found that analogy insufficient, way too rough for the local environment. In Italy, some of those same situations are like "ciao" situations, but some others are like "buongiorno" situations, and others still like "salve" situations.

Notice how here we're talking about a second language, but the difficulty is not really one of knowing the meaning of words. Hofstadter already knew what the various Italian salutations meant. What he struggled with initially was the right circumstances that warrant the use of each word.

That's language: saying the thing you need to say when, where, and how you need to say it. The "what" is only a fraction of the story.

And, of course, such asymmetries in language are one of the things that make translation difficult. When you translate an Italian book or film to English, all those fine distinctions between "buongiorno", "ciao", and "salve" get collapsed into "hi", "hey", "hello", none of which have a neat 1-to-1 correspondence in terms of inciting situation. In terms that I've written about before, the Fundamental Framing of one language sets different boundaries to that of another language.

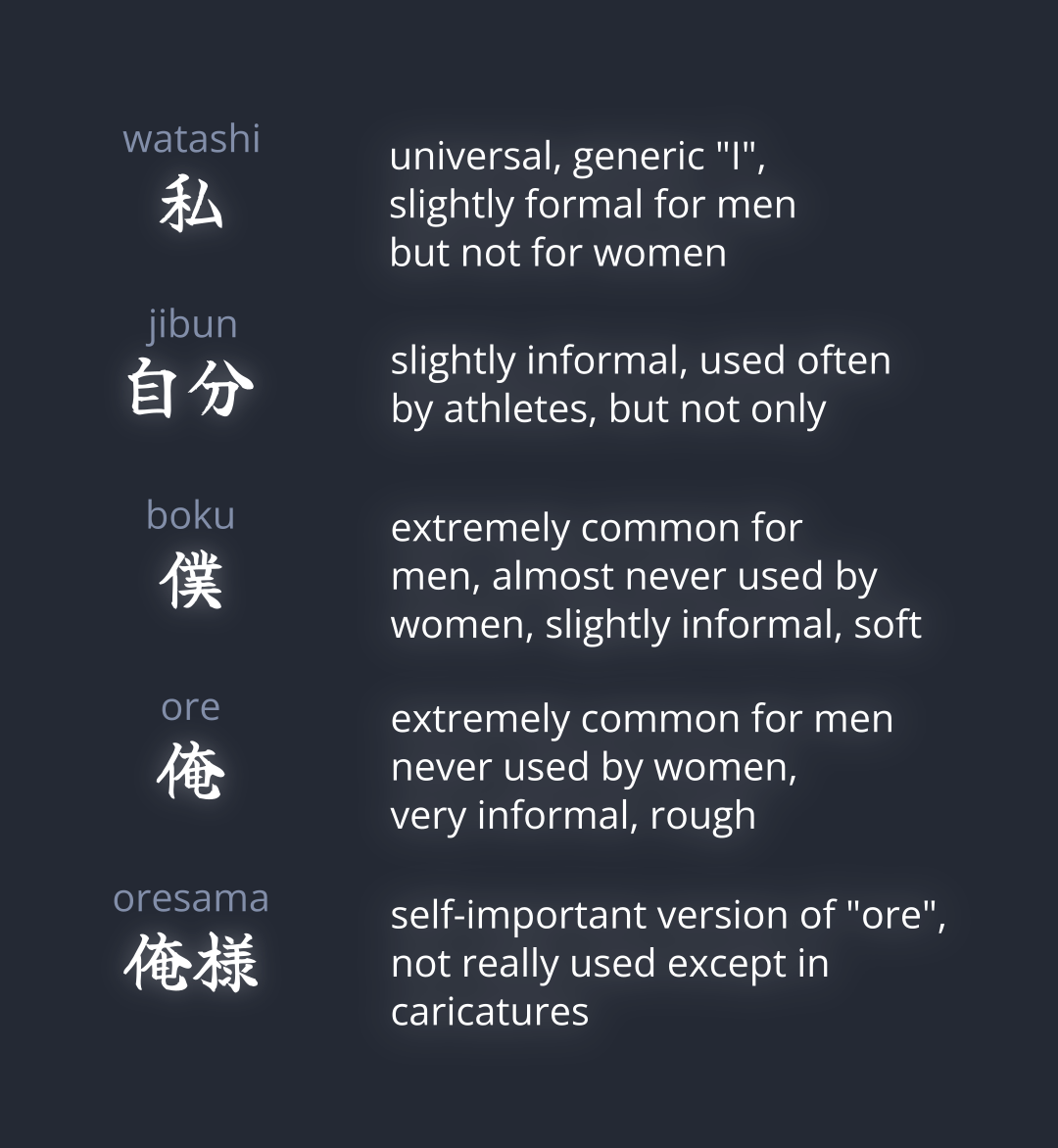

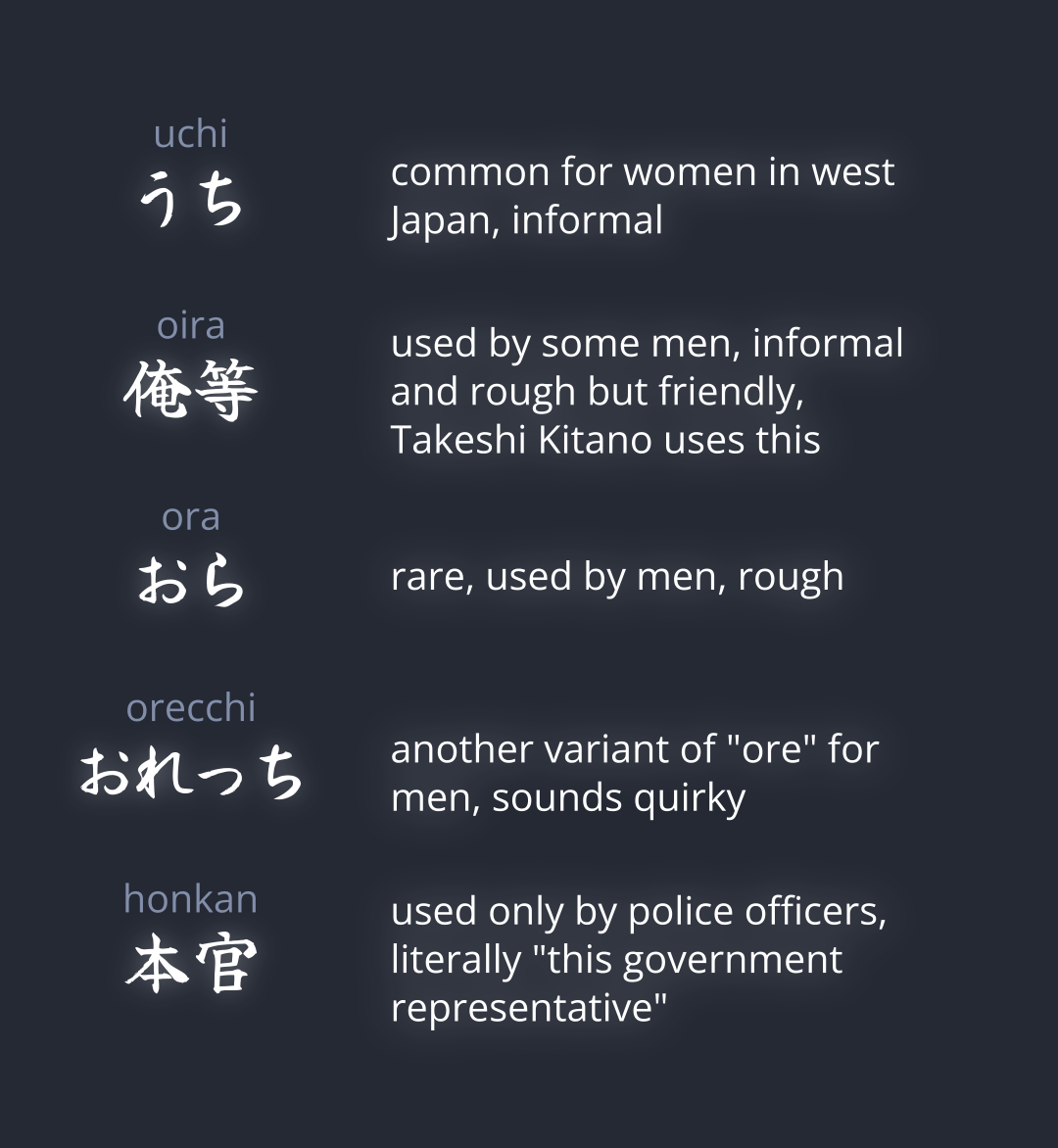

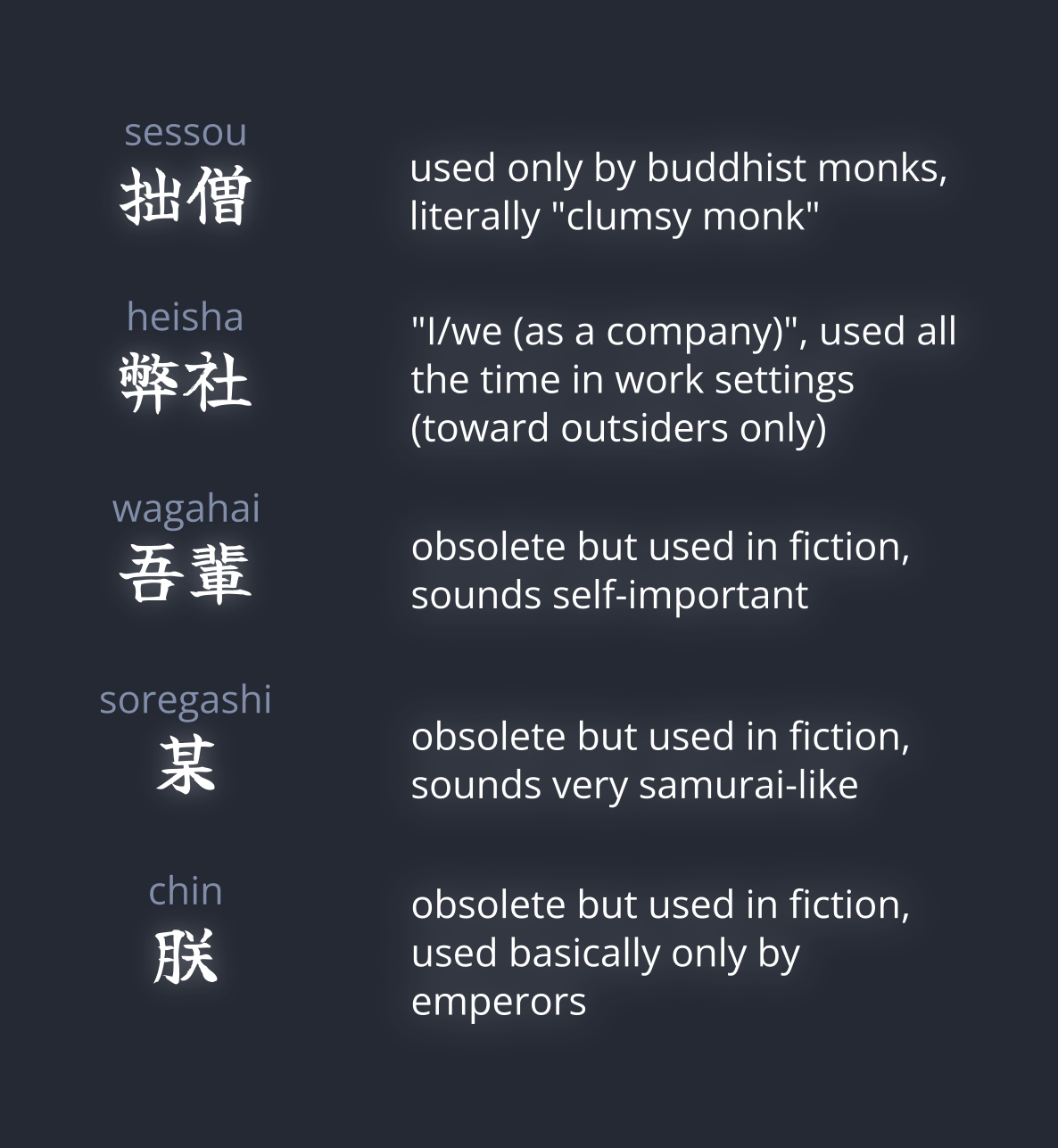

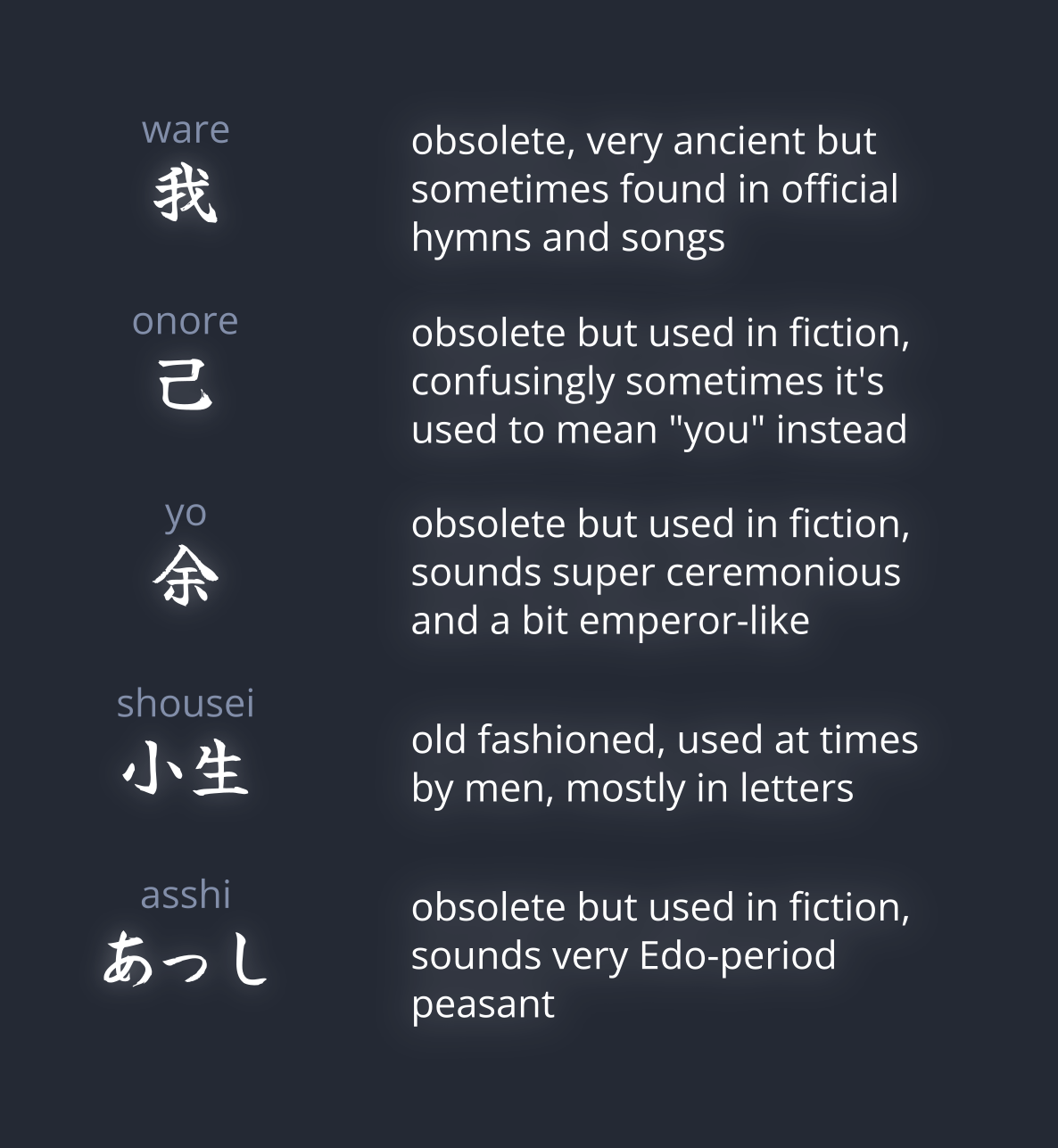

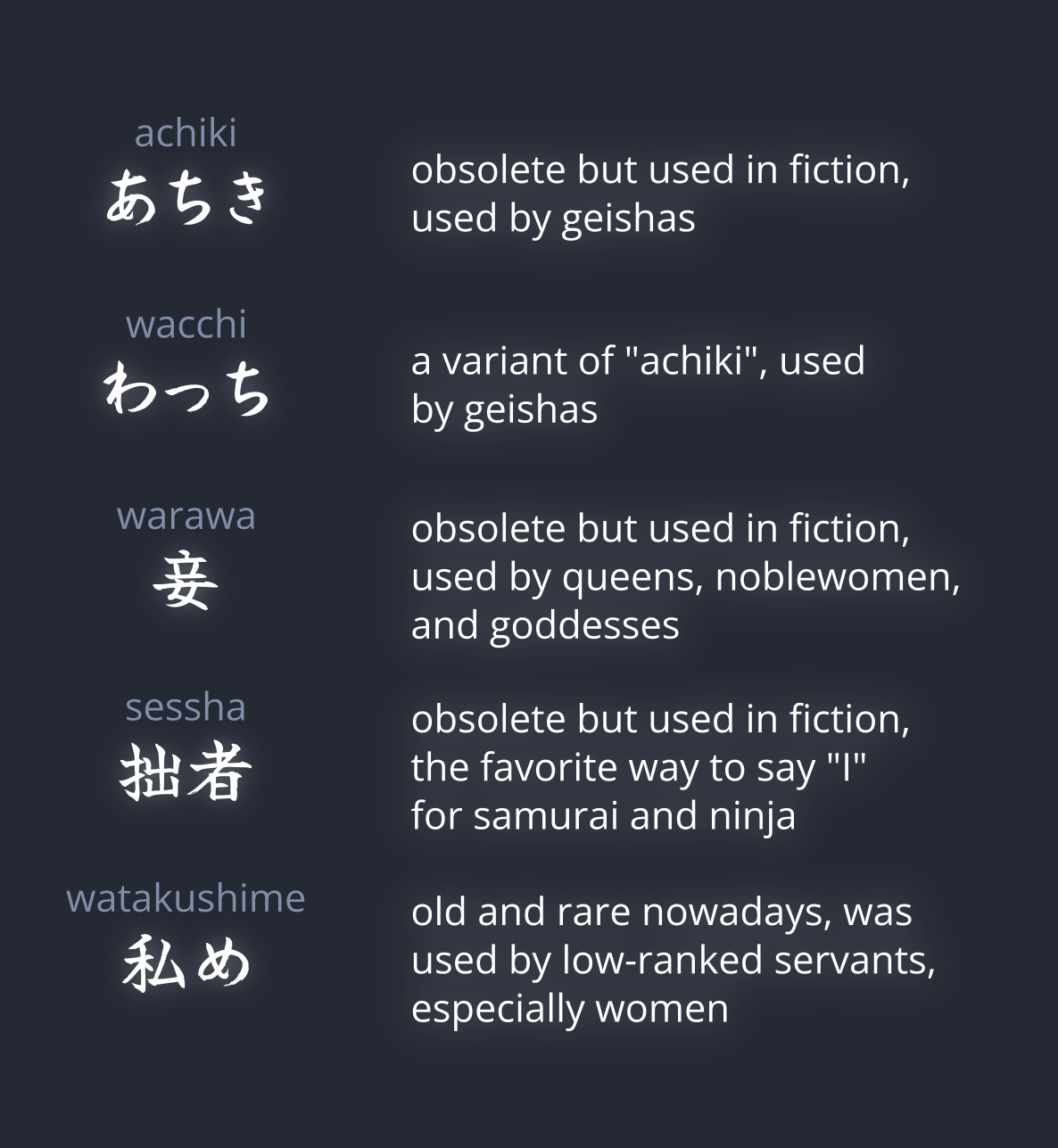

For a more extreme example of the same problem, look at how many ways there are to say "I" in Japanese, based on the circumstance:

Another popular way to say "I" is by simply saying one's own name (there is no third-person form in Japanese grammar). Calling oneself by one's name is used mostly by children, but many adult women use it in intimate settings, carrying a frank, slightly indulging tone.

These are the 30 (+1) most common ways to say "I", those I'm confident every Japanese can recognize. Each carries its own nuance, and tells you something different about the person who uses it, the relationship they perceive to have with the listener, and the formality of the setting. To make things more interesting, each Japanese speaker switches between several of these throughout the day.

In fiction, Japanese authors are experts at orchestrating these options to convey more than the mere words do, to recall archetypes, and to distinguish the characters' personalities.

Yet, an English translator is forced to take all those flavorful self-appellations and roll them up into the single, sublimely neutral "I".

Translation succeeds by degrees.

Beautiful Moons

Perhaps the most famous story about translation in Japan is an urban legend featuring Natsume Souseki, considered by many to be the greatest Japanese novelist of the early 20th century.

When he wasn't writing future classics, he worked as an English teacher. One day—the story goes—his students were trying to translate the English phrase "I love you" to Japanese. They knew the translation for each of those three words, so naturally they constructed a grammatically valid sentence with them. How hard can it be?

When they asked Souseki to check their translation, however, he told them they'd gotten it all wrong.

"Japanese lovers don't say things straight to each other's face like that," he said. "You'll do better to translate it as, isn't the moon beautiful tonight?"

The story itself may be apocryphal, but the message rings true. There is a side of translation that has less to do with the meaning of individual words than with the intention of the speaker. You forgo a literal translation in favor of one that uses different words, but achieves the intended meaning more closely. This approach—usually called "free translation"—exists for all languages, but it's especially important when the two languages in question are very different. Japanese (to/from) translators are forced to do this kind of work all the time.

(It is telling that Japanese Wikipedia has an article about literal vs free translation, while the term "free translation" isn't even mentioned on English Wikipedia)

For example, watch this famous scene from Akira Kurosawa's Sanjuro. The protagonist Sanjuro, an able but rough samurai, has done something that humiliated his friend Hanbei. Hanbei wants to regain his honor, so he challenges Sanjuro to a duel to the death.

Sanjuro tries to dissuade Hanbei, saying

I'd rather not. If I do, one of us must die. It's not worth it.

All three sentences are rather loose translations of the original, but that last "it's not worth it" is really a free translation. The literal equivalent of the Japanese tsumaranee ze (つまらねぇぜ) would be "it's boring".

Now, someone saying "it's boring" about killing a comrade would sound rather odd in English. For an English speaker, this is not like a "boring" situation. The translator correctly extracted the intention of the character—read between the lines—and conjured different words for it, "it's not worth it". This works, although it loses some of the flavor of Sanjuro's mannerism.

Of course, we need free translation in both ways. There's a famous quote from the Godfather:

I'm going to make him an offer he can't refuse.

In the Japanese version of the film, the subtitles could have used a direct translation of those words, because they are all unquestionably "translatable". Instead, the translator wrote (I re-translate back literally), "I won't make him complain" (文句は言わせん). This sounds weird in English, but in Japanese it carries just the right flavor for the scene, the right balance between sounding innocent at first, but lending itself to a violent reinterpretation later on. On the other hand, the literal translation would sound clunky and overly formal in Japanese.

What's Translation, Then?

It boils down to this: words are not self-contained packets of information. Every word spoken or written exists in a specific cultural context and in a specific circumstance. Take those away, and the word loses its function. In a sense, every word is its own little inside joke.

Nowadays, developed countries are close enough to each other culturally that roughly the same kinds of situations happen in all of them. Because of that, most of the words of one language will have a rather neat equivalent in those of most others. But there are always corner cases, words and expressions that developed in a peculiar way for historical and cultural causes that did not take place in other languages. How do we square that with the Turing-completeness of language?

At its core, language is a tool to influence other people for some purpose. Even if it's just to make the other laugh, or to enjoy the time together, we don't use language unless we have a goal to achieve. This is a point expressed well by Nick Enfield, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of Sydney:

When a surgeon turns to her assistant and says “Scalpel,” this one-word linguistic act—we might call it a command or a request—is, first and foremost, an instruction for mutual coordination. The key to understanding this is that when you use language, you are never just saying something. You are doing something. With words, you act on those around you, to help them, influence them, build affiliations with them.

— Language vs Reality, Why Language Is Good for Lawyers and Bad for Scientists, Nick Enfield

But if language always has a goal, then the real test for its effectiveness is how well the goal is achieved.

Each word has its own goal, but it also needs to support the broader goal of the sentence containing it. The sentence, in turn, needs to support the goal of the longer text or speech segment around it. A word that conveys its own strict meaning but confuses or weakens the intended effect of the words surrounding it is a failure of language.

If self-contained definitions were translations, you wouldn't need to learn a language or hire a translator. Having a dictionary at hand would automatically grant you native level comprehension and output quality, if not speed.

This leads to a simple and general definition for what translation is:

Translation is achieving the goals of the original text in a different language.

Now we can tackle the titular question.

Translatability Tests

If the original message is good enough for the speaker's purposes, but it's not good enough in its translated form, the language hasn't been translated.

As a corollary to that, a message is translatable only if the translator can convey the same desired nuance in roughly the same amount of time or space. Shedding some of the intended nuance will not cut it. Conveying the nuance at the expense of a much larger number of words will add interference and destroy the proportions and timing of the message, both of which (proportions and timing) are usually instrumental to achieving the original goal.

That's why we use code-switching: if we can get away using a word in Language 2 on the fly while speaking Language 1, that's far preferable than any alternative approach. In a text, if you need a translator's footnote to complement what is common knowledge in the original language, the point may get across, but it's an explanation, not a translation.

Another test: if translators regularly give up translating a word, opting for free translation or for words with a much distorted or diminished nuance, than that word is untranslatable. (This happens often with certain language pairs.)

Also: if a term would require a significant cultural shift or national re-education program in the target language just for it to be understood seamlessly, it's probably safe to call it "untranslatable".

It's Doubly Worth It, Sanjuro

In short, I believe that translation is about more than conveying the same meaning. It's meaning, plus nuance, plus contextual cues, plus format and timing. Meaning itself is always transferable to other languages, this is true. But those other things are another story. Untranslatable words, and words that lose most of their intended effect when translated, do exist.

This is good news, because it's one more reason to learn other languages.

The first reason, the obvious one, is that it allows you to communicate directly with people who speak that language. That's a precious thing on its own. But the second reason, validated by the existence of untranslatable bits of language, is that knowing a language opens up a whole different world for you that would simply be inaccessible otherwise. ●

Cover image:

The Godfather, 1972