Living in a Real World, Acting in Imaginary Ones

On our Virtual Physics and Tunnel Vision

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

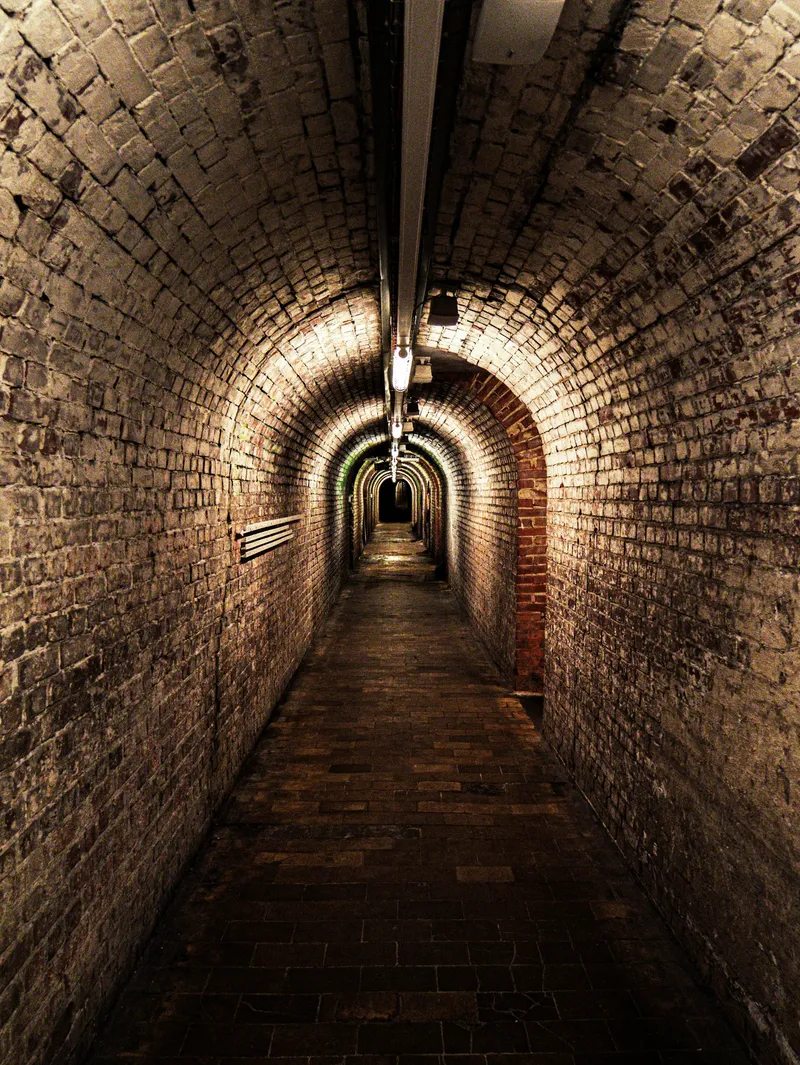

Cover image:

Photo by Miguel Bruna, Unsplash

I

When the story of Matsuri Takahashi's karoshi ("fatal overwork") suicide became public, around 2017, it hit me harder than I would have thought. I recognized it as a tragic, extreme, and all-too-natural extension of the social dynamics that I saw every day around me, as I was immersed in Japanese work culture.

I felt some of those same forces at play on me and on the people around me, although I was very lucky to join welcoming, open-minded workplaces, where no one tried to actively shame me into working longer and harder, and people were kind and polite regardless of hierarchy. Even there, many of my Japanese colleagues worked until late night every day, didn't use any of their paid leave, and seemed to be able to think about nothing other than work. Although I didn't think it would affect me personally, the topic fascinated me. Sometimes it terrified me.

Why didn't Matsuri simply quit her job? When her seniors bullied her and made her feel worse than useless, why didn't she just walk away? In her tweets, she sometimes mused about quitting and suing her company. She even mentioned having signed up for a job search consultancy: wasn't that the ray of hope she needed to break out of the hellish environment she had stumbled into?

Did Matsuri Takahashi have to die? Of course not—but she clearly believed she did.

When I wondered about these things, I did so not with condescension, but with apprehension. She had been a young, extremely bright person, with an education that would have opened the doors of any job for her, who nevertheless fell into an overpowering death spiral defying all reason and rebellion, apparently set up from the beginning to lead her to killing herself. What if that spiral caught me, or a loved one, too?

Around the time these thoughts were disturbing me, I started dating someone. I liked her very much, but her profile and situation also alarmed me: Japanese, in the same age group as Matsuri Takahashi, and herself trapped in a job she hated, with abusive, male chauvinist bosses who constantly gaslighted her. The first time we talked, she admitted she had been thinking about quitting for years already but never seemed to be able to do it.

In other words, she lived in the same world Matsuri Takahashi had lived in. The questions I had been wondering about became more relevant than ever for me. I didn't want to see my partner slide any deeper into the spiral.

The usual ways we approach this problem are meaningful: the direct causes of karoshi in Japan, and of much workplace suffering all over the world, are the gaslighting and other mental manipulations perpetrated by heartless jerks for their selfish purposes; broader causes are the cultural backgrounds and various systemic dehumanization traps, especially strong in places like Japan and South Korea but present everywhere else, too; depression and other mental disorders, which can magnify these problems, too often go undiagnosed and untreated. It is important and useful to discuss these problems and to act at these levels: they should not be left unchecked.

But others have explicated these issues better than I could. My own question, the one I want to personally explore and fully understand, is this: how can all that apparently unnecessary suffering even be possible?

The root enabling cause of all that seems to be in the very nature of human consciousness, and to affect us much more often than those extreme cases of self-destructive stress. I think it's a problem of Virtual Physics and Tunnel Vision.

II (Virtual Physics)

As a thought experiment, imagine I completely lost my ability to make predictions about reality. Suddenly, I have no idea what to expect from any of my actions or from external events. Will the sun rise tomorrow? No idea. Will a stone fall up or down, or left or right, when I let it go? I just can't tell. If I give a command to my arm and hand to bend and scratch my nose, will I actually scratch my nose or will a unicorn spring out of nowhere and stab me to death? The only way to know is to try. Even if I do manage to scratch my nose, this won't help me next time I wonder the same thing, because this sickness prevents me from learning anything from experience.

I would not survive for long in this scenario. Making projects and achieving goals would be out of the question. Most likely I would starve myself to death, because I can't imagine which actions would actually lead me to food. I might even suffocate myself by ceasing to breathe, because I can neither predict that asphyxiation is the outcome, nor that resuming breathing again is the simple solution.

Making predictions about what might happen in the future is one of the most fundamental functions of our minds. As Donella Meadows said, "everything we think we know about the world is a model". After all, we think and "experience" with our brains, pale lumps of jelly hidden in the pitch-black insides of thick boxes made of bone. We can't and don't think about the world directly: we refer to streams of highly fragmented, distorted, and contradictory data from our sensory organs to form mental representations of the world in our minds, and then we manipulate those mental objects to make guesses about the future. Those approximate representations are what I call "black boxes", and the way we segment the world into distinct things is what I call "framings". I wrote about these things here and here.

This is not solipsism, a belief that the real world doesn't exist and "the world is an illusion". The real world is out there, all right. We get hints and measurements of it through our senses, and we use them to form and update our framings and models. But we think, decide, and act in those simulated worlds that exist only in our heads.

This inner simulation works very much like a video game does. Some entities or objects are defined, and they behave following prescribed rules. When Mario jumps, he falls back down. When you attack an innocent shopkeeper in an RPG, the AI-driven city guards will retaliate by attacking you. These are worlds with rules and predictable "if-this-then-that" chains that you need to learn and navigate to exercise your free will, which happens in the parts of the game that remain unconstrained.

Like video games have "physics engines" to power their virtual physics, so do our brains create a Virtual Physics to predict the world.

Psychologists and philosophers talk about "naive" or "folk" physics to indicate the intuitive, uneducated understanding that every human being has of the laws of physics. They also talk about "folk biology", for our intuitive, uneducated understanding of the organic world, and also "folk linguistics", "folk psychology", and so on (all of these have their Wikipedia pages, and are categorized under folk science).

While you might need different tools and backgrounds to fully study how these intuitions work in people, they must be the result of the same kind of process, the same "engine", under the hood: neurons buzzing each other to simulate things, abstract black boxes interacting with each other following some laws—accurate or not. For this reason, I will refer to all of these "folk sciences" as Virtual Physics.

Models are always abstractions of the thing they model. Every belief and snippet of knowledge, then, is Virtual Physics, regardless of its layer of abstraction: physical, social, psychological, video-game, fairy tale—it makes no difference. If you give a name to something and convince yourself that it will tend to do certain things and not to do other things, and that it "has" certain distinguishing properties, then it becomes just another object (black box) in our simulations, a pawn in our mental game of predicting the future as accurately as possible.

Notice how we're not required to understand how those black boxes work internally. Education, and scientific progress in general, gives us detailed explanations of the workings of things, but those only help us refine our predictions: they don't fundamentally change how we think about things.

This extremely multi-purpose approach to simulation, supporting anything from physical laws to social and psychological cause-and-effect, allows us to make predictions about basically anything, and even to immerse ourselves in worlds that could be, and impossible worlds that will never exist.

III (The Limits of Virtual Physics)

This black-box function of our brain is amazing. It's an extremely powerful solution that has evolved and expanded over time to make living things more and more effective at staying alive. Whenever competition arises, those who can "see" further into the future have an enormous strategic advantage against the more mentally myopic. In fact, I think this might be the only viable solution for truly multi-purpose future prediction, even from a theoretical point of view. The only alternative would be to somehow become Laplace's Demons, all-knowing creatures with enough memory to contain the whole universe and enough attention to track every quantum of energy at the same time.

Unfortunately, these amazing models that keep us alive are just that: well-meaning caricatures of reality. In order to be useful, they have to be simplifications, approximations, linearizations, and, to some extent, misunderstandings of the actual systems they refer to. The art is not to use the "right" models—which don't exist—but merely to find models that are "good enough for their job".

I wrote above that we improve and sophisticate our models by learning. Your "naive physics" knowledge of gravity, for example, is enhanced or replaced by what the physics professor teaches you, and that allows you to predict—mentally or with pen and paper—the future possible behavior of more things: instead of just knowing that an unsupported stone will fall downwards, you can predict where the stone will fall if thrown at a certain velocity and direction, and what orbits it will take if thrown in outer space.

But there is a limit to how much we can cram into our intuition, even with education. You might have learned the rough principles of car engines, but you're not thinking about them every time you press the accelerator. Unless you have special reasons to focus on them (e.g., when your car stops in the middle of the highway) you still treat the car as a black box: "if I press this pedal, the car goes faster."

In other words, even when we do obtain better mental models through education, our brains seem to be doing constant work of greedy simplification in order to streamline our thoughts. This must be another evolutionary trick, and another double-edged sword.

IV (Tunnel Vision)

Problems come up when we forget that our decisions and actions happen entirely in a virtual, partial, uncertain world. Instead of seeing our mental models as probabilistic guesses of what might happen, sometimes we make the mistake of seeing them as immovable truths.

Some of our mental simulations are so ingrained in our minds that their predictions begin to feel inevitable or impossible, uncertain outcomes ossifying into absolute laws that (we think) cannot be escaped. Whether caused by common sense, social pressure, superstition, or simply ill-informed models, this is a trap we fall into all the time. I don't know of a perfect word for this phenomenon, so let's call it Tunnel Vision.

This use of "Tunnel Vision" shouldn't be confused with the literal tunnel vision of one's eyes, or the psychological tunnel vision linked with confirmation biases. The simple definition of the Tunnel Vision I'm talking about is

you're trapped because you believe you're trapped.

Look at the sentences I highlighted in black in the post about Matsuri Takahashi. See how, despite viscerally hating her oppressive workplace, she also firmly believed that her situation was normal: "this is what society is like." Even when she tries to joke about it, she can't help telling us what she believes to be the rule of life:

When you can't tell if you're working to live or living to work, that's when real life begins.

— Tweeted at 8:22 PM, November 3, 2015, emphasis mine Her most telling metaphor must be the one she tweeted on December 8, 2015, less than three weeks before her death, when she compared herself to "a salmon swimming upstream to spawn". What she is saying—what, perhaps, she is hoping to exorcise by framing it as a joke—is that such a painful life annihilated by work, fear, and humiliation is her biological destiny, the natural behavior written in her DNA.

Reading her announce, resigned, "no wonder people die from overwork," chills me to the bone every time.

In Matsuri's Virtual Physics, even death was more natural an outcome than quitting her job. Her Tunnel Vision was such that running away from her workplace was merely a fairy tale, one she should be ashamed for contemplating.

Was it her fault then? Was Matsuri Takahashi responsible for "forgetting" that she had better options? Of course not. While no one has a life of toil and abuse written in their DNA, we all have to live with the limits of Virtual Physics. Tunnel Vision pervades humanity, affecting all of us in serious and in mundane circumstances.

Tunnel Vision is at work when strongmen oppress and subjugate groups of people who don't rebel despite having the numbers to do so successfully.

It's there when family members are able to bully family members for whole lifetimes.

I see it often in Japan, when my colleagues tell me they "can't" use even half of their contractual paid leave. "Why not?" I ask them. "I just can't," they reply. And when, like my partner back in 2017, they claim to have been dreaming of working for a non-abusive company for a long time, yet have been "unable" to take the necessary steps for the better part of a decade.

I see it also in the befuddling cases of mass hysteria, in the deep-rooted racism and discrimination against minorities, and in the demonization of "the enemy".

It's often in the eyes of those who give up, saying, "I'm naturally bad at it"; of those who miss out when rare opportunities present themselves, giving up on them not because they don't ardently wish to take them, but out of shyness, or "it would be rude to ask...", or "they would never consider someone with my background..."

I see it, of course, in myself, when I realize I was upset and riled up over a minor thing as if it was a giant moral issue; and when I can't seem to stop thinking about work for days at a time.

How often we decide that the world is certainly, clearly like the shaky simulation we've contrived on impulse, based on precious little evidence!

V (Escaping Habit)

When Tunnel Vision grips you, your world becomes smaller, simpler, claustrophobia-inducing. You forget that there is a vast and varied universe around us, an infinity of options and opportunities. You see the gray walls of your room and mistake them for the horizon. Tunnel Vision means that your Virtual Physics is over-constrained. It makes you something less than you were. And it locks out the notion that you are not really forced to be in the situation you're in. This is what causes the bad kind of stress: being caught in a world too tight and narrow for you.

When does this kind of Tunnel Vision happen? It's not only a matter of losing track of the Big Picture and of using oversimplified models of the world, because those are not always bad things. Being in a state of "flow", hyper-concentrated on a familiar task, works by "forgetting the world", too, and it's usually a good thing. All is fine if you're able to zoom in and out of your hyper-focus at will. Put another way, it's not Tunnel Vision if you can "open the black box" and re-expand your framings to something more realistic when necessary. Being focused is great if you're able to snap out once you're done.

Tunnel Vision only happens when mental automatisms replace the conscious assessment of what is possible here and now, and then prevent you from going back.

It happens, for example, when the habit of thinking "I should work until 3 AM, otherwise my boss will bitterly humiliate me" crystallizes into "I should work until 3 AM because that's what work is like," and when "I haven't been able to understand these topics yet" degrades into "I'm inherently too stupid for this," and when "if she doesn't wash the dishes today, the kitchen will be a mess" becomes "if she doesn't wash the dishes, she's being mean to me."

Our natural and useful tendency to simplify our models ("pushing the pedal makes the car go faster") becomes a liability when we get so used to them that we lose the capacity to un-simplify them. In most cases, this seems to be caused by the mind-numbing repetition of the same task, by gaslighting from our peers, by being stuck in the same restricted environment for a long time, or by some combination of these. In other words, any situation in which some part of the mind is induced to switch off for long periods at a time.

The way out is not to convince ourselves that Virtual Physics is wrong, only that it can always be wrong. It's also not about realizing that Virtual Physics is "fake", "just" a simulation—it's as real as it gets, otherwise society wouldn't function—otherwise Matsuri Takahashi would still be alive. I'm saying we need to remind ourselves and each other that this is how we work as human beings, and this, sometimes, is how we die.

Every now and then, simply remembering that you might be stuck in a virtual tunnel of despair is enough to crawl out of it with your own strength and save yourself. Often, though, you're just too deep in to even remember that you can be saved. That is why we need to remind each other, break the spell of harmful social and cultural conventions, call out the mind-manipulators, talk about it.

Epilogue

My partner, in 2017, was caught in the same world that tragically crushed Matsuri Takahashi. I could see that she was unable to fathom how any job could be less painful than her current detestable job—the only one she had ever experienced. The idea of resigning provided no ray of hope for her, only fear of retaliation.

So I told her. I told her over and over, for months, that fun workplaces do, indeed, exist. I told her that "real life" was not what she thought: there are companies where all colleagues respect you and value you and won't judge you for taking care of yourself, for enjoying your life beyond work. I pestered her with the idea that any brief pain and abuse that would surely be unleashed on her when she announced her decision to quit would be small compared to the years of daily grinding away at her mental health.

It took a while for her to break out of the spell and take action, and the action was painful as expected, but she did it with her own strength. She left and never looked back. I'm happy to see that she now lives in a world where joy and optimism are possible, even probable. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Miguel Bruna, Unsplash