Primitive Atlas of Glass Circuits

Aren't we all air converters?

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

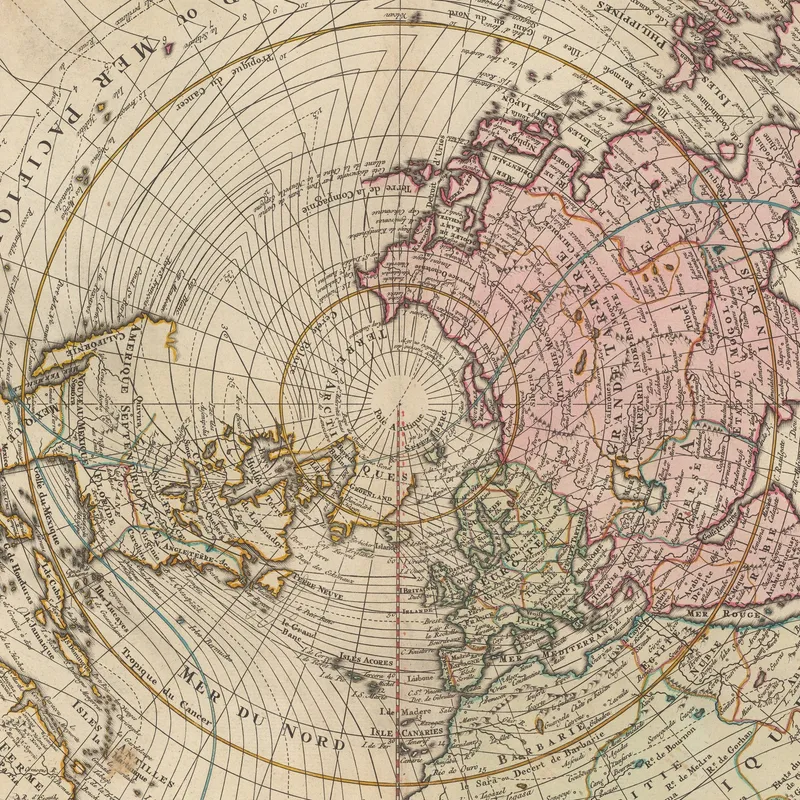

Cover image:

Second edition of Gerard Mercator's map of the North Pole or Arctic

How much work can a simple framing do? Here is as simple a framing as they get.

In this view of the world, there are only two kinds of things: "stuff" going around and "systems" where something happens. It doesn't matter what the system is, as long as some kind of "stuff" can pass through it. It's so general that you may think it almost useless, but think again! It's enough to change how we see the world, and its generality means it can tell us something about anything.

I first introduced this model on Plankton Valhalla, in an essay titled Toying With Ideas of Glass Circuits. There, I made the point that we must seek different ways to segment the world, bring down the walls that separate the disciplines of human knowledge, and seek new connections between apparently unrelated ideas. Thinking in terms of systems is great for this, and I tried to show that with the disarmingly simple diagram above.

Looking at that picture, there aren't many questions you can ask without getting into the nitty-gritty of concrete examples. Here is a fully general one, though: do those two elements—"stuff" and systems—change a lot, a little, or none at all in the process?

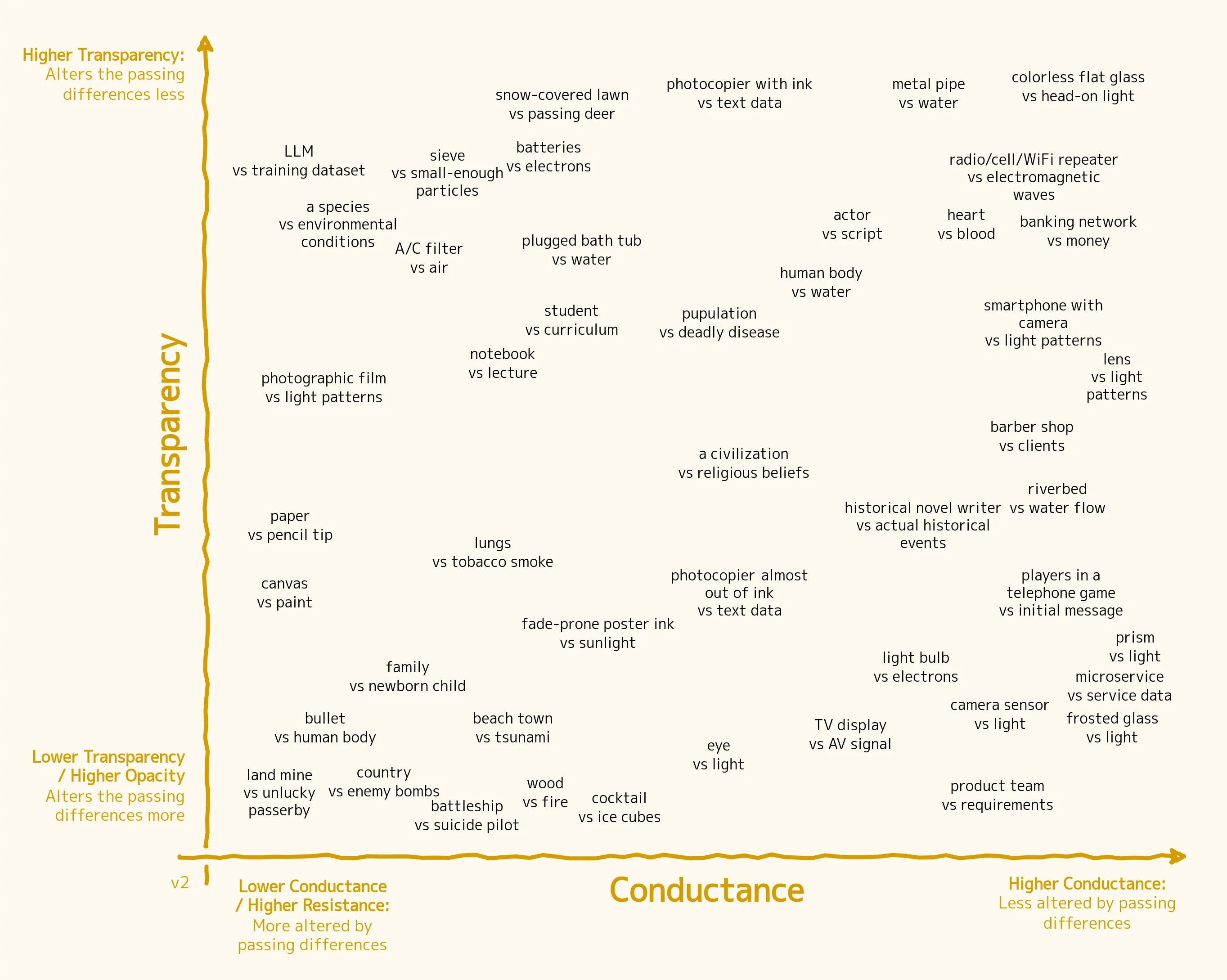

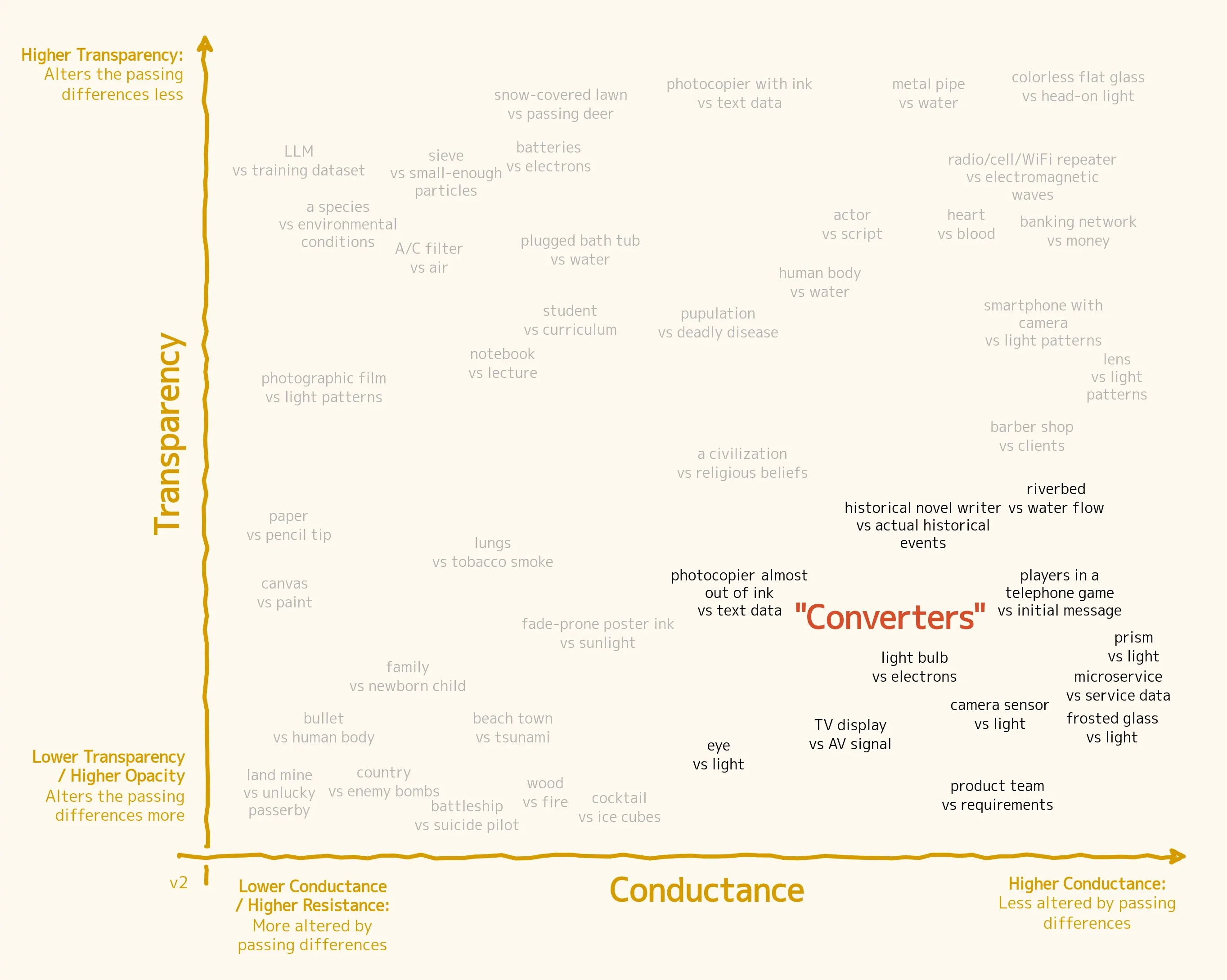

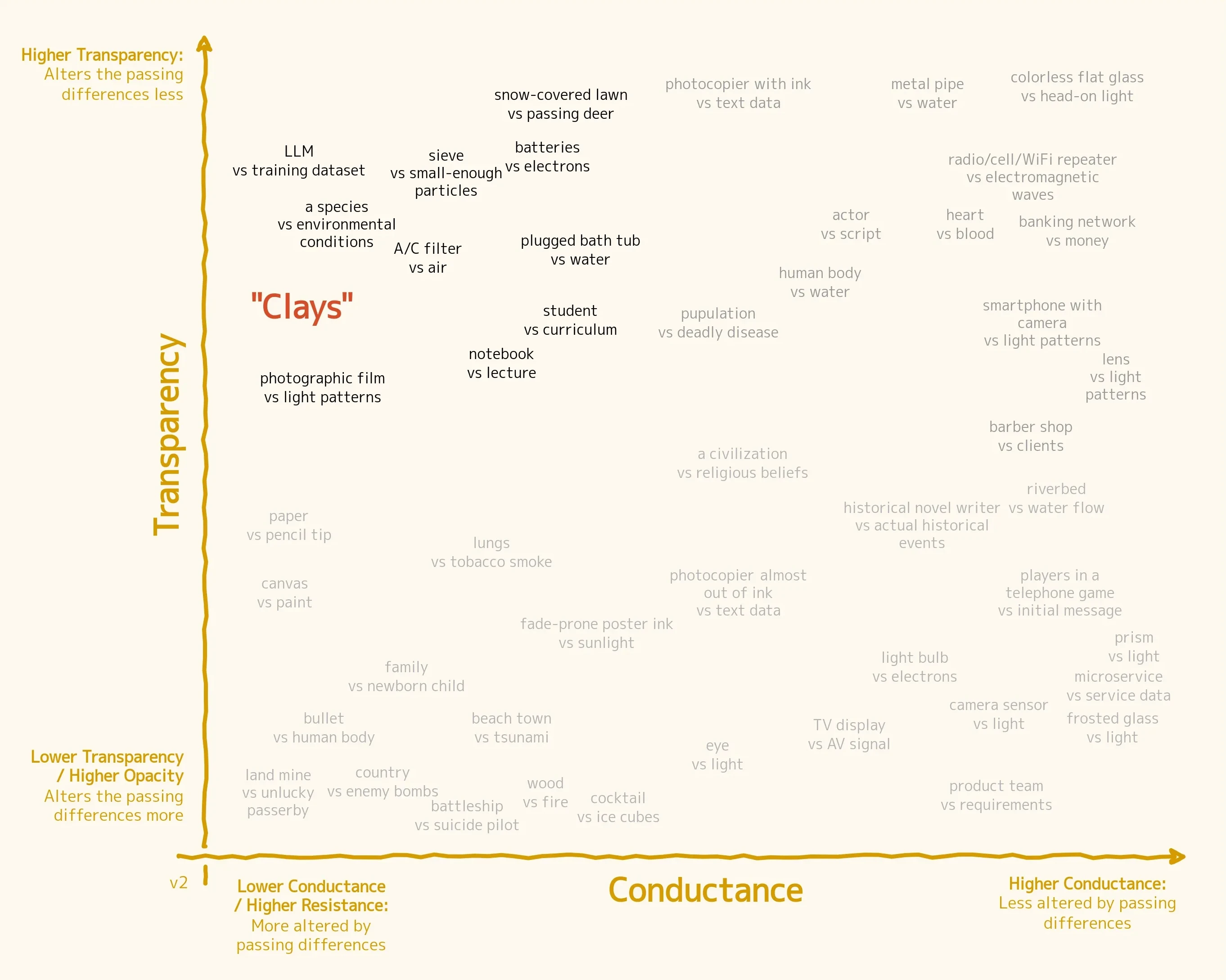

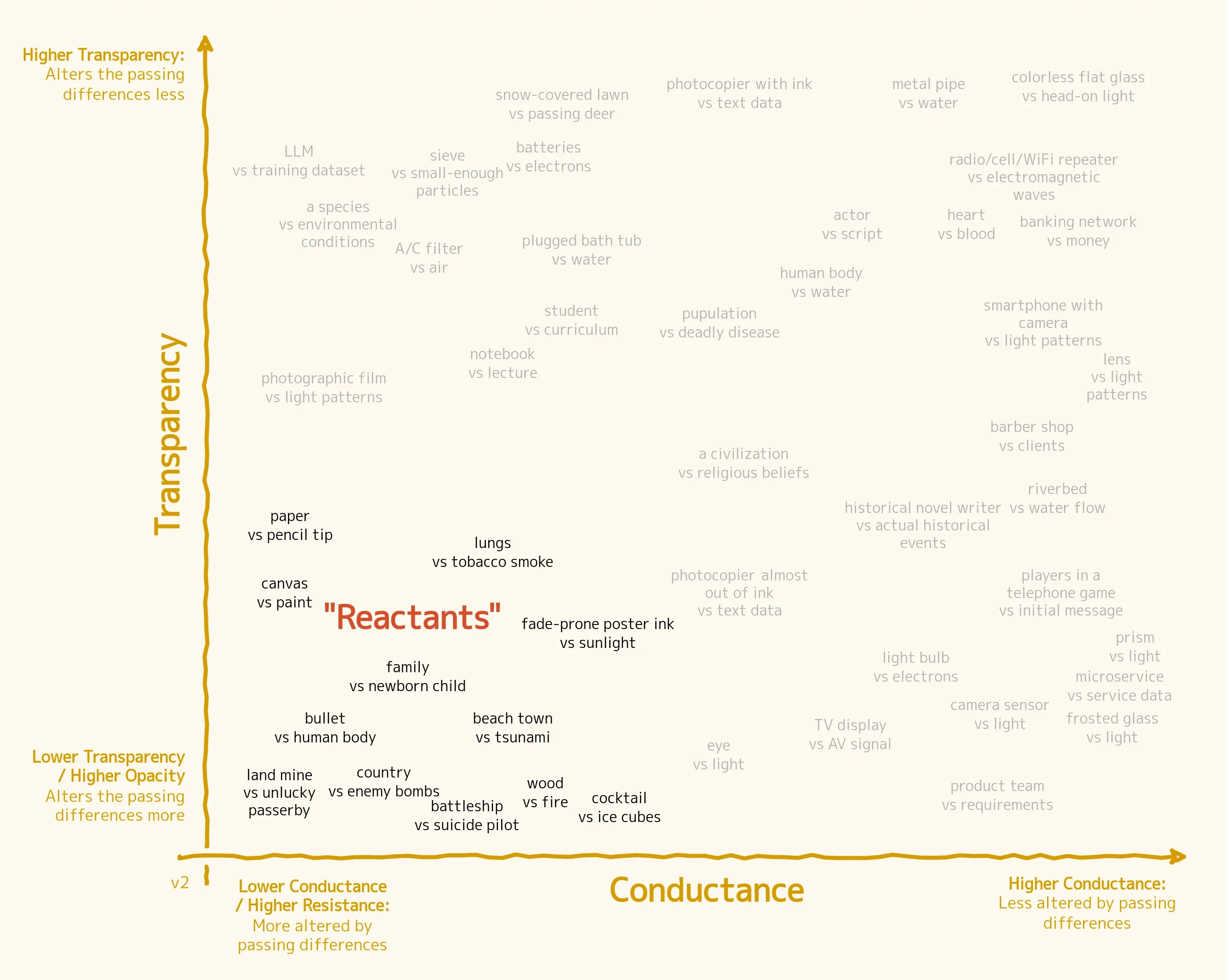

The following "Glass Circuit Chart" is what came out of that exercise.

There's a lot of information in that chart, so let's break it down. First, the "stuff" I'm talking about is what we can call differences—that is, the property of things of not being like some other things.

Differences as in “here, not there”, “this much, not that much”, “machine that does what I want, not inert piece of metal”. Whenever you can talk about something or some amount as unlike others, there you have a difference. Everything [...] is made of lots and lots of differences, and it will do different things, be different things based on what those differences are.

The word “difference” as I use it here covers pretty much everything you can think of. [...] If you can talk about it, you’re talking about its differences.

Why use this peculiar concept of "differences" instead of "objects", "matter", or "energy"? Because, with systems, the patterns of organization are what matters, and those need not be in the form of objects, matter, or energy (although they often are). Differences are a more universal, agnostic idea at the base of any kind of pattern. We'll see plenty of concrete examples below.

At the most fundamental level, then, differences of all sorts go in and out of systems, and whatever happens inside those systems happens to and between differences.

The question was whether there is any change in the system and in the "stuff" (the differences) going through it, and how big of a change that is. This is actually two questions, which translate into the two axes of the chart:

- System conductance: How much does the system change when certain differences enter it? The analogy with the electrical conductance (and its opposite, resistance) of a circuit is based on the observation that, in more resistive materials, the collisions with incoming electrons make the atoms vibrate, producing heat. More conductive materials remain relatively unscathed by the current. Similarly, a more conductive system lets specific differences pass through it without being affected by them.

- System transparency: How much do those differences change as they pass through the system? Intuitively, something transparent lets the images of objects on the other side pass through unchanged, while a more opaque material degrades or transforms them. In our framing, a transparent system is one that lets differences through without transforming them.

In this sense, a system has the properties of both a circuit and a glass: a "glass circuit". The answers to these two questions are different for each pair of system and incoming differences, and that allows us to place each pair somewhere on that Cartesian plane.

Clear glass, for example, is both highly conductive of visible light (the glass transmits the light while remaining unchanged by its passage) and highly transparent to it (the light is unchanged), so we place it in the top-right corner of the diagram.

On the other hand, if now you take the same "visible light" differences but look at what they do in a "photographic film" system, the answers are quite different. The patterns of light that touched the film become impressed there. The film, which was originally blank, is greatly changed by this process. The light patterns, however, are preserved for the viewer of the picture, albeit to a limited extent, because some colors and details may be altered. We can thus put this pair, "photo film vs light", somewhere to the far left, midway along the vertical axis of transparency.

Most of the time the definition of a system and of the differences traversing it can't be very accurate, because of how reality works and because of limitations in the language we use to describe them, so that their position on the Glass Circuit Chart is hard to pin down precisely. As I wrote in the original essay, this is definitely not an exact science. But there are meaningful distinctions between how things work in this framing. It is a different way to draw boundaries, which implies the elimination of other boundaries, too. In this view, very disparate systems turn out to have some very fundamental features in common.

The implications of these newly found links are often exciting new research directions, but this Chart is largely unexplored territory. I don't understand most of it. But since we have this toy, someone's gotta play with it!

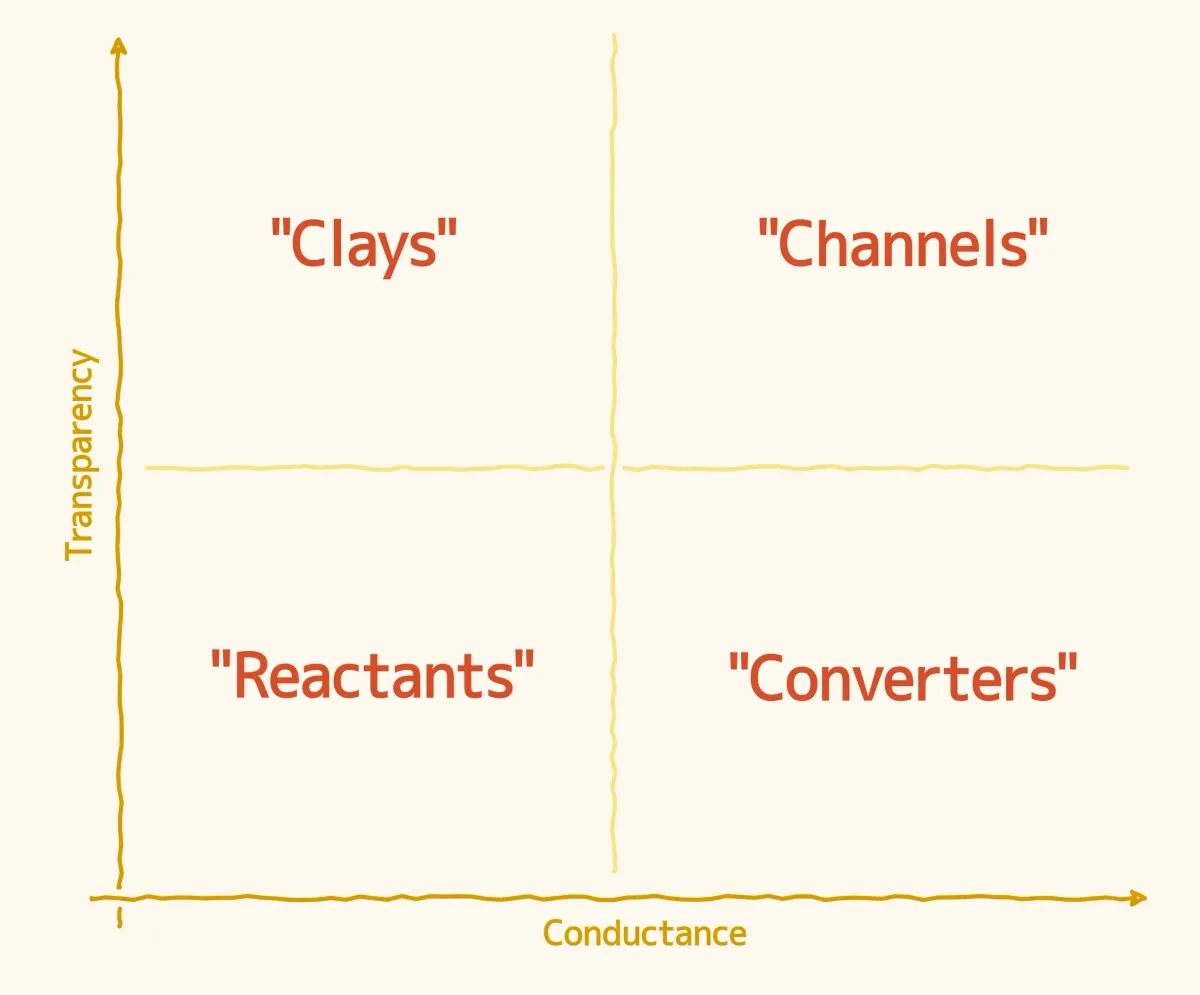

Here is a primitive Atlas of Glass Circuits, barely detailed enough to make out four "continents" on this strange map.

The following are my brief interpretations (and bizarre names) for these four "systemic continents". For each of them, I will also mention how that category of systems can be employed by evolution or by people for specific outcomes.

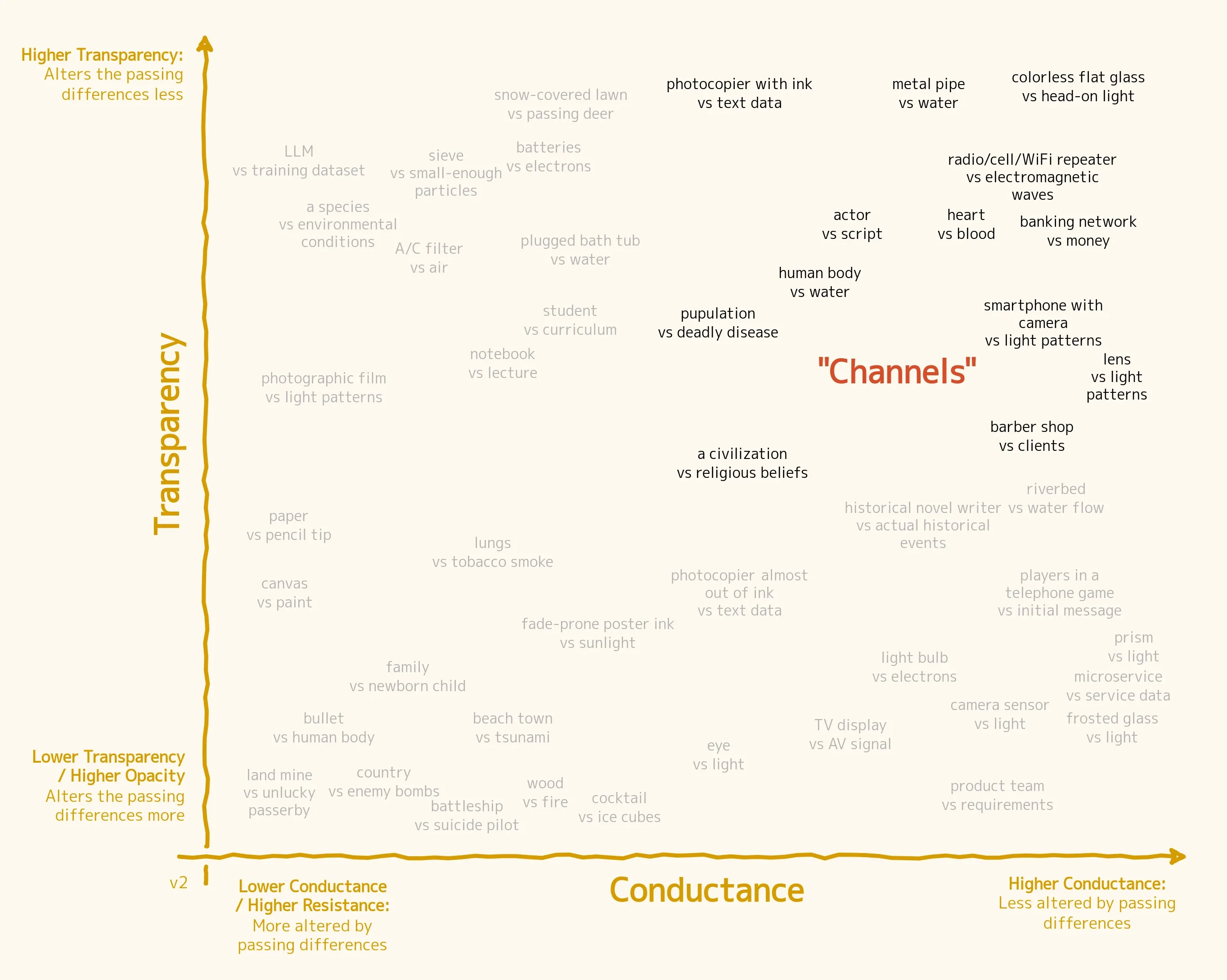

The Channels

The top-right quadrant of the Glass Circuit Chart is reserved for systems that are both highly transparent and highly conductive of their associated differences. I will call them channels.

An old-fashioned plumbing pipe is, of course, a channel because it transfers water without significantly changing it or being changed by it. The same goes for a Wi-Fi repeater, which picks up a weak signal and repeats it, unaltered, with more power. Also, a country's postal system, and each individual mailman and mailwoman (along with their means of transportation), would qualify as channels with respect to mail.

Some interaction is happening here, otherwise we wouldn't say that those differences are inputs to the system, but the interactions are only (or mostly) in the form of transport and relay, not transformation. Channels have the property of extending the reach of specific differences.

This property is useful for engineers. Sometimes we use channels to move matter or information from one place to another without tampering with it, like with moving walkways or fiber-optic cables. Other times, we want to filter and sort things, and we can achieve that by using systems that are only channels for one desired type of difference and not another, like a window pane that allows light through intact but blocks the passage of insects and rain.

Channels are used extensively in the bodies of plants and animals: blood vessels, nerves, esophagi, cell membranes, roots, xylems. In sensory systems, they are necessary to forward differences from the outside—like sound waves and light—to the brains and proto-brains hidden deep inside the animals' bodies. The more transparent they are, the better for this purpose.

The Converters

South of the channels is the region of the converters. These systems are just as unaffected by differences that pass through them, but this time they do alter those differences. What comes out is not the same as what goes in.

This is a fun category because it's about the systematic transformation of certain differences into different media and formats. A light bulb trades electric current for photons, just as a team of software engineers turns a set of written requirements—like the specifications of a new mobile app—into an actual mobile app.

Sometimes the transformation is nothing more than a mangling of the input: think about frosted glass for light or an encryption program. But it is more often interesting to convert the differences into a form that can be fed into some other system, like when an AV signal from a cable gets translated into a pattern of pixels on a screen.

Chain several converters in a row, and you have a—literal or metaphorical—assembly line. In fact, it doesn't even have to be a linear chain because we can (and very often do) create cascades and networks of converters that together form bigger and more complex converters. Every machine and computer is an example of that, and every living organism too—the channels that shuttle differences from the eye to the brain would be useless if there wasn't a converter called "retina" that turned patterns of photons into patterns of neural excitation.

Converters are how the purposeful transformation of the world happens.

The Clays

Some systems are transparent to the differences passing through them but are reshaped by them. These are clays, in the top-left corner of the Glass Circuit Chart.

A battery's internal structure mutates as it shuttles electrons from one end to the other, for instance, and eventually stops doing that. In fact, one way to see clays is as "unstable channels". In the short term, they behave like channels, transmitting differences quite faithfully to some other place, but in general, that very process makes them lose such ability. It's a negative feedback loop.

From the perspective of a human engineer, this property of clays is often undesirable because it gives a short lifespan to whatever they're building. How nice would it be to have batteries that don't discharge and air filters that don't clog up! In these cases, we only use clay systems because we have no other option.

Other times, though, clays are indispensable because of their pliability, not despite it. The process of adaptation of a species or ecosystem to its changing environment—without significantly damaging that environment—is a hallmark of evolution, and those systems need to be clay-like to make that happen.

On a smaller scale, learning is possible only for systems in the clay quadrant. A student wants to be changed by the information given to them, and, at least initially, strives to be able to reapply it as accurately as possible without undue alterations. Similarly, an LLM is designed to be molded by the observation of enormous amounts of training data, itself unaltered by this process.

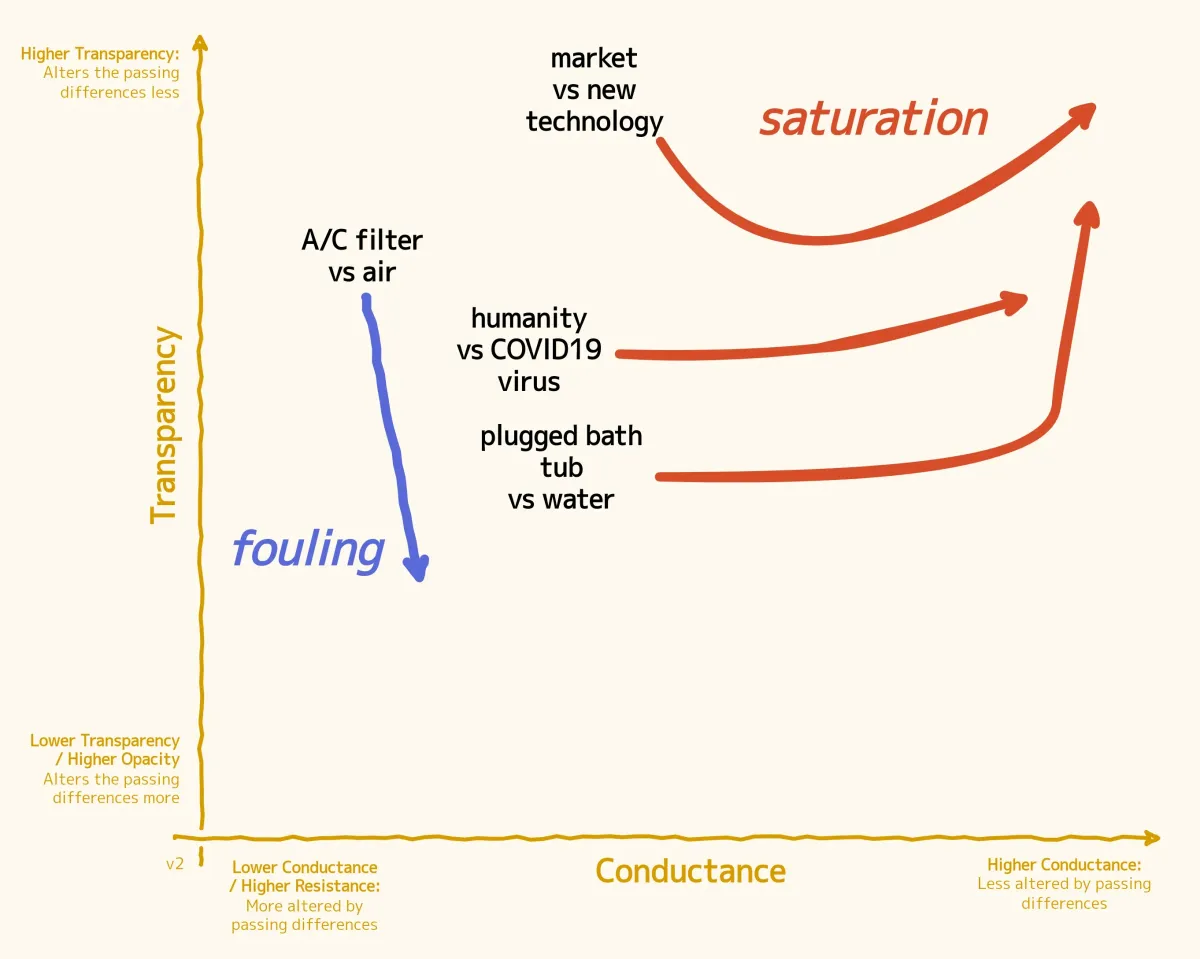

Because clays are unstable, they often tend to migrate away from that corner of the Glass Circuit Chart. For example, an A/C filter may be relatively transparent to the air from the fan, only removing microscopic particles from the flow. But as time goes on, the blocked particles will keep accumulating on the filter, gradually degrading its ability to fully transmit the air current. Eventually, if it isn't replaced sooner, the filter will be completely blocked, and no air will be able to pass through it anymore. On the chart, this translates to a gradual descent from the upper-left quadrant to the lower-left one, a process that we could call fouling.

Another possibility is that the clay system instead moves to the right, becoming a channel. An example of that is an empty tub into which you begin pouring water. For a while, the tub will "absorb" the water without emitting it elsewhere because the water remains trapped inside it. If you wait long enough, however, the water will begin overflowing, and you'll get a stable flow of water out of the tub that is identical to the flow of incoming water from the tap.

This is analogous to what happened to the human population when the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread around the world. For a while, humanity suffered tremendous harm, deeply changing on many levels because of the virus's deadliness, but by the fourth year after the outbreak, most people had become resistant, and the virus itself had mutated to less harmful variants. The virus continues spreading, but its transformative effects on society have subsided, and in this sense humanity has become a channel for that specific virus. This rightward migration of a clay system might take the name of saturation.

The Reactants

Finally, we have the lower-left quadrant, which I'll call reactants. I borrow this word (a bit loosely) from chemistry, where it is used to indicate chemical substances that are consumed or transformed during a reaction. In this quadrant, everything is transformed: neither the system itself, nor the differences that enter it, remain the same as before.

This category of systems is broader and more varied than the other three. As a matter of fact, the vast majority of things out there probably fall in this corner of the chart. It is the default type, because most things in the Universe change in an interaction—if anything, the other three quadrants are the special cases, with their unusual feature that at least one side of the system-input pair remains stable in the course of an interaction.

Channels, converters, and clays may sometimes be formed by the lucky (or guided) migration of reactants to their corners of the Chart, but that is a rare occurrence. The Universe, in other words, is a bubbling sea of change, with small islands of stability here and there.

Because of such an extreme variety, this quadrant is the most complex and hard to model. Since everything here mutates all the time, these systems tend to be so short-lived that it may not even make sense, in practice, to define them as systems. Even the distinction between what constitutes the system and what, instead, counts as the differences traversing it becomes blurred and ambiguous here: they're all mutable differences after all.

The easiest examples that I can think of, both natural and human-made, are about destruction. (So much so that I was initially tempted to call them the "bombs".) You might be tempted to believe that these processes, inherently uncontrollable and unpredictable as they are, can only be useful to annihilate rather than build. But there are positive examples as well: the arrival of a baby into a family or of a new member into a team, the landing of paint on canvas, the mingling of two genomes during sexual reproduction. Reactant systems are simply about total transformation, in a neutral sense. What constitutes destruction or creation is a matter of point of view.

That concludes my brief survey of this vast systemic landscape. It feels a bit like the endearingly inaccurate world maps of the middle ages, with only the vaguest resemblance to the actual landscape they try to replicate.

I intentionally avoided adhering to the traditional ways to draw boundaries between categories and disciplines—an exercise that we do, perhaps, too rarely. Who knows, maybe one day I, or someone else, will figure out ways to refine and make exact these mapping techniques. ●

Cover image:

Second edition of Gerard Mercator's map of the North Pole or Arctic