Culture Is the Mass-Synchronization of Framings

What exists is a matter of public opinion

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

The Four Seasons; Spring, Christopher R. W. Nevinson

1

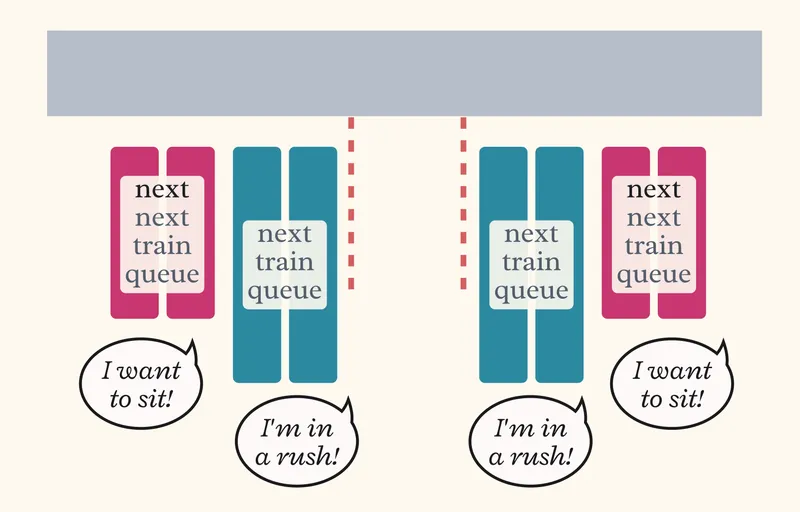

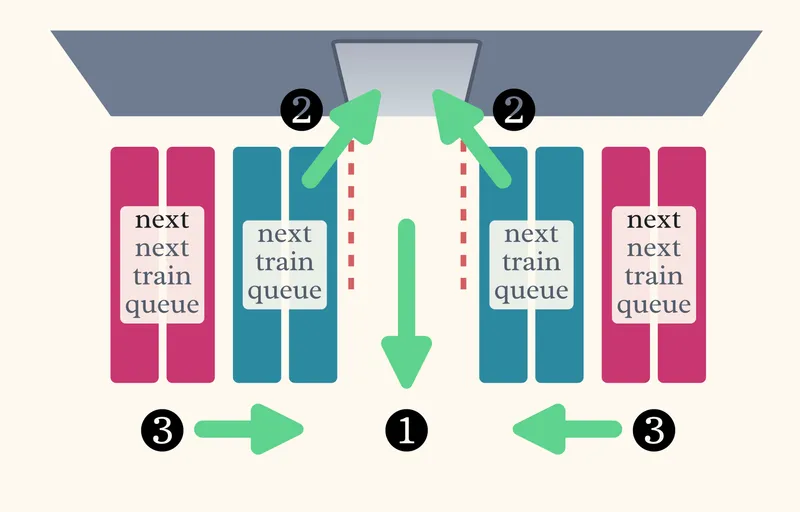

If you descend onto the Marunouchi Line platform in Ikebukuro Station on any weekday morning, you will witness an unusual train-boarding ritual. Like in any other Japanese station, people wait in line at the two sides of where each train's door will open. This is called seiretsu jousha (整列乗車, orderly boarding), and is a universal standard in Japan. Unlike most other stations in Tokyo, though, on Ikebukuro's Marunouchi platform people will form not one but two queues on each side. One of these queues, the one closest to the doors, is the senpatsu (先発, earlier departure) line, and will board the next train that comes; the other, shorter, queue, is called kouhatsu (後発, later departure) and is waiting to take the place of the senpatsu line: they'll skip the next train, and board the one after that instead.

When the new train arrives, first everyone waits for the passengers to get off (the "orderly boarding" common sense), then the people in the senpatsu queue all get in, and finally the people in the kouhatsu queue shift laterally on the platform to become the new senpatsu. A new kouhatsu queue immediately starts forming in its now-vacated place.

This is a rather strange way to do things. Why not simply form one kind of line, and use the age-old first-come-first-served approach? Why would anyone ever choose not to try boarding the next train? And why is this procedure used in the Marunouchi Line in Ikebukuro and not in the many other lines in the same station, or (for that matter) on most other lines and stations in Tokyo?

The key to it all is the observation that Ikebukuro Station is a terminal of the Marunouchi Line, so all trains always start empty on that platform. This double-queueing ritual gives passengers a tradeoff that would not be available in most other cases: speed vs comfort.

If you're in a hurry, you can directly join the senpatsu crowd and be (almost) guaranteed a spot on the very next train, but forget about sitting down—be ready to stand squeezed like a sardine. If, on the other hand, you have plenty of time, you may decide to get in the shorter kouhatsu queue—which will become the front of the senpatsu once the next train leaves—and you'll be (almost) guaranteed a comfy seat in your long commute.

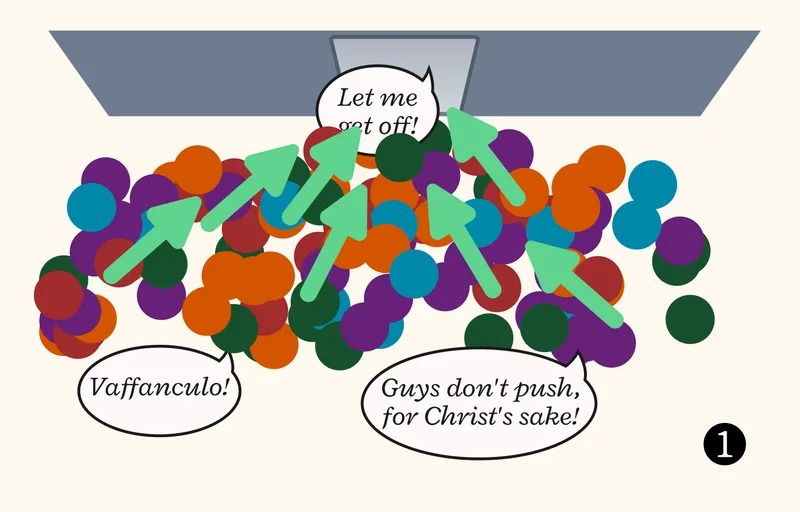

For an Italian like me, this whole process is nothing short of a miracle. I grew up in a city where metro train boarding during rush hour feels like a prelude to the apocalypse.

Many Italians can come up with the idea of waiting for passengers to get off before boarding themselves, but most crowds there lack the restraint to apply it with any kind of regularity. When it comes to the strategy of directly aiming for the next next train, though, I wonder if it has ever even occurred to anyone south of the Alps.

The miraculous thing about the Japanese method is that there is no authoritative "director" standing next to each door and yelling at people where to stand. There are "senpatsu" and "kouhatsu" signs on the ground, but no detailed instructions or explanations. I doubt it is taught at school or anywhere else, either. People just seem to know, and to naturally implement the whole process without exchanging so much as a word with each other.

Are these people human?

Live in Japan as a foreigner for a while, and you'll see miracles of this kind everywhere. No one steals, even when people leave their purses and smartphones and wallets unattended in plain sight for half an hour at a time; no one litters; no one disturbs fellow train passengers by talking loudly or making phone calls; and people are extremely polite and go out of their way to help you if you ask. In Japan, you will only witness restraint and patience, even in the face of rudeness and selfishness from strangers. What kind of DNA compels them to behave in such a coordinated and collectively useful manner?

Of course, I know that there is nothing innate in the miraculous "Japanese Way" because expats living here quickly adapt to the same behaviors.

It's not just the ethnic Japanese that correctly follow the senpatsu/kouhatsu queueing system, for instance. All the long-time expats I know in Japan are—at least in public—just as polite, restrained, and rule-following as the average Japanese, regardless of their nationality. I wrote that no one steals unattended wallets in Japan, not that no native Japanese steals.

In fact, the sure-fire way to spot a tourist in Tokyo is not by their appearance or the language they speak, but by how loudly they talk in public, or how they stand in spots that inconvenience other people. They're not trying to disrupt, they simply haven't had enough time to assimilate the local behavioral patterns.

Those miraculous scenes have nothing to do with the Japanese DNA: it's their culture. And culture is, by and large, random, arbitrary, and self-reinforcing.

2

You can go and look at the history of Japan, their institutions past and present, their religious philosophies and military values, and you can point to many things that seem to "explain" why today's Japanese are polite, orderly, and ultra-civilized. This is a mistake, though, because all it does is kick the can a little farther down the road. Why were those institutions and philosophies like that? Why did the first samurai become so honorable?

Simply going farther back in history only repeats the mistake. You won't find a final answer, because the answer is not at the beginning, it's in the ongoing process itself: chance and contingency. People behave the way they do because, period.

If that seems implausible to you, think about simpler cases you might witness anywhere in the world. When a corridor is being traversed by crowds of people moving in both directions, two or more lanes will form spontaneously: the first two people trying to avoid each other's path will randomly dodge either left or right; the people behind them will find it more convenient to follow the path of those walking ahead, and very quickly everyone is walking in a line on "their side". Whether those going northward walk on the left and those going southward on the right, or the other way around, doesn't matter, and no one really cares. It's just arbitrarily become the easiest thing to do, and it stays that way as long as there are enough people in both directions.

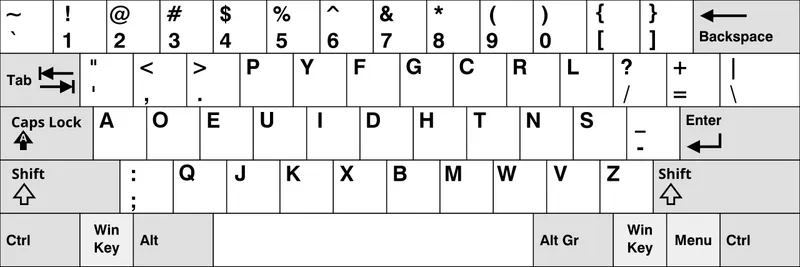

Sometimes there is a good initial reason behind a cultural standard, but that reason becomes irrelevant later on. The QWERTY layout of English keyboards started as a clever design for typewriters—it helped minimize jamming of the mechanisms—but is now completely meaningless and even sub-optimal for modern digital keyboards.

If these things are simply cultural and arbitrary, why can't people change them, then? Well, have you tried changing the rhythm of a mass applause by clapping in a specific way? Or typing with a DVORAK keyboard?

Once a self-sustaining feedback loop has started, how it started ceases to mean anything. Mindless forces emerge that suck you in a specific direction.

3

So far, it sounds like what gets "synchronized" between people living in the same culture is their behavior and habits. This is true, but I don't believe it's the whole, or even the main, story. What I'm talking about is not a unification of actions but of the thinking patterns from which those actions arise. Culture is the mass-synchronization of framings.

A mental model is a simulation of "how things might unfold", and we all build and rebuild hundreds of mental models every day. A framing, on the other hand, is "what things exist in the first place", and it is much more stable and subtle. Every mental model is based on some framing, but we tend to be oblivious to which framing we're using most of the time (I've explained all this better in A Framing and Model About Framings and Models).

Framings are the basis of how we think and what we are even able to perceive, and they're the most consequential thing that spreads through a population in what we call "culture".

You're forced to learn this (at least in the abstract) when you begin noticing some apparent contradictions in the collective behavior of Japanese crowds. Non-residents tend to think that the core tenet of Japanese culture is to "obey the rules" or "do things properly", but that is absolutely not the case. How do you explain the fact that some rules are ignored by literally everyone here?

- People in Japan never follow the written rule to switch off your phone in the "priority seats" area of each train carriage (it's a precaution for those with pacemakers).

- People always actively climb escalators, despite incessant written and vocal requests that people stand still for safety reasons.

- Flows of people in corridors very often form lanes that go opposite those indicated by the signs on the floor.

The list goes on. The more you pay attention, the more collective infractions you'll notice.

Sure, these are mostly small transgressions of little consequence, and they are not enforced in any strong way. But if following the rules were a core value of Japanese culture, why would that matter?

The real core value of Japanese culture (or one of them) is something like "never stand out or make a fuss". Nowhere in that principle is a strict requirement to follow the rules. In fact, it's perfectly fine, in Japan, to break the rules as long as that's what everyone does and expects you to do. In terms of framings, the Japanese culture has acquired—by arbitrary and unimportant means—a definition of the concept of (or a "black box" for) "standing out" that differs from its equivalent in many other cultures: instead of being generally neutral, it is seen as intrinsically unpleasant and embarrassing.

The behavior that stems from employing this ontological "thing" (this particular flavor of "standing out") in your mental models is what you see manifested on the train platforms, on the escalators, etc.

The Italian culture has the concept of simpatia that translates awkwardly to English as "being a mix of likeable and/or charming and fun to be around" and doesn't even exist in Japan. I do believe that having this compact and convenient idea of simpatia makes Italians more conscious of the importance of being simpatico and seek that property in others. It drives their behavior in more or less explicit ways.

Similarly, English (as most Western languages) has a cultural black box for what we call "sarcasm", but this black box is largely absent from the Japanese cultural framing: sarcasm is simply not a thing in Japan, and people aren't (I'm tempted to say can't be) sarcastic. It doesn't occur to them to be it.

Each culture is made of shared framings—ontologies of things that are taken to exist and play a role in mental models—that arose in those same arbitrary but self-reinforcing ways. Anthropologist Joseph Henrich, in The Secret of Our Success, brings up several studies demonstrating the cultural differences in framings.

He mentions studies that estimated the average IQ of Americans in the early 1800's to have been around 70—not because they were dumber, but because their culture at the time was much poorer in sophisticated concepts. Their framings had fewer and less-defined moving parts, which translated into poorer mental models. Other studies found that children in Western countries are brought up with very general and abstract categories for animals, like "fish" and "bird", while children in small-scale societies tend to think in terms of more specific categories, such as "robin" and "jaguar", leading to different ways to understand and interface with the world.

But framings affect more than understanding. They influence how we take in the information from the world around us. Explaining this paper, Henrich writes:

People from different societies vary in their ability to accurately perceive objects and individuals both in and out of context. Unlike most other populations, educated Westerners have an inclination for, and are good at, focusing on and isolating objects or individuals and abstracting properties for these while ignoring background activity or context. Alternatively, expressing this in reverse: Westerners tend not to see objects or individuals in context, attend to relationships and their effects, or automatically consider context. Most other peoples are good at this.

How many connections and interrelations you consider when thinking is in the realm of framings. If your mental ontology treats most things as largely independent and self-sufficient, your mental models will tend to be, for better or worse, more reductionist and less holistic.

4

The definition of "framing" that I'm adopting on Aether Mug is more precise than what people use in general, and for this reason I don't know of any study that specifically tested how framings evolve in social interactions. But I don't think I'm making a bold leap by saying that we experience, at a deeper level, the same form of synchronization between framings that we can trivially witness between surface behaviors.

It might take longer, but if everyone around you talks and acts based on the assumption that concepts A and B exist with certain properties, and no one ever mentions concept D or acknowledges it with their behavior, you will gradually shift to think in terms of A and B and not so much in terms of D. Given enough time, the ontological status of D in your mind might atrophy and vanish in the background, while A and B's status solidifies.

Somehow, the commuters on Ikebukuro's Marunouchi platform have acquired clear and distinct concepts for "senpatsu queue" and "kouhatsu queue", both of which are absent from the framings of Italian commuters. The "miraculous" part is not that any of them can conceive the idea—any Italian would have no trouble understanding it and following it if those around them did the same—but that feedback loops emerged to reinforce them in the whole commuter culture.

Like in the emergent walking lanes in a corridor, once these recursive forces have gained traction, it's almost trivial for newcomers to learn them as "rules" and comply. As is often the case, here the shared framing led to the rules, not the other way around.

In this case, the emergent cultural rules have clear advantages for everyone: more choices, less stress, everyone wins. But it is not true, in general, that all framing synchronizations lead to better behaviors.

The basic force behind all culture formation is imitation. This ability is innate in all humans, regardless of culture: we are extraordinarily good imitators. Indeed, we are overimitators, sometimes with unfortunate consequences.

Overimitation ... may be distinctively human. For example, although chimpanzees imitate the way conspecifics instrumentally manipulate their environment to achieve a goal, they will copy the behavior only selectively, skipping steps which they recognize as unnecessary [unlike humans, who tend to keep even the unnecessary steps]. ... Once chimpanzees and orangutans have figured out how to solve a problem, they are conservative, sticking to whatever solution they learn first. Humans, in contrast, will often switch to a new solution that is demonstrated by peers, sometimes even switching to less effective strategies under peer influence.

— The Psychology of Normative Cognition, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, emphasis theirs.

We have a built-in need to do what the people around us do, even when we know of better or less wasteful ways. This means that we can't even explain culture as something that, while starting from chance events, naturally progresses towards better and better behaviors. That's what science is for.

Once the synchronized behaviors are in our systems, when we are habituated to certain shared ways of doing things, these behaviors feed back into our most basic mindsets, which guide our future behaviors, which further affect each other's mindset, and so on, congealing into the shared framings we call culture, i.e.: whatever happens to give the least friction in whatever happens to be the current shared behavioral landscape.

This is why, often, formal rules and laws do indeed take root in a culture: not because they're rules, but because the way they are enforced creates enough friction—or following them creates enough mutual benefits—that, like in the corridor lanes, crowds will settle into following them. This is also why, perhaps even more often, groups will settle into the easy "unruly" patterns.

Maybe the Japanese culture tends to have more extreme examples of this than others because of its meta-cultural framing: not only is imitating others a natural human tendency, but here it has also become a self-reinforcing loop in itself. Imitate the imitating. ●

Cover image:

The Four Seasons; Spring, Christopher R. W. Nevinson

Comments

Loading comments...