Darwin the Witness

In His Own Words (Episode 4)

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Volcano Osorno, Voyage of the Beagle

This is the fourth episode in the series of curated quote collections "Darwin in His Own Words".

- Darwin the Fun-Loving Young Fellow

- Darwin the Voyager

- Darwin the Man of His Times

- Darwin the Witness

- Darwin El Naturalista

It should be clear by now that Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle is much more than a log of scientific notes. Descriptions of nature and its mysteries abound—we'll see them in the next episode—but his book is also a window into his own character, an adventure story, and a reminder of the glaring ethical blind spots that are possible even in well-meaning, brilliant people. There is one other major aspect of that narrative I haven't done proper justice to yet: it's a tantalizing snapshot of those thriving and tormented lands during an interesting period of their history.

Some of the places surveyed by the Beagle had been wild, near-uninhabited lands until very recently (roughly 3 years for the Galapagos, mere decades for New Zealand and Australia). Others had been colonies for up to three centuries, but were in periods of turbulent political change: Brazil had just become an independent empire, while Argentina was a maelstrom of conquest, persecutions, and civil wars unfolding under the British crew's very eyes. Half-unwittingly, Darwin immortalized a fast-transforming world—customs, political situations, and ways of life that were both new and just about to vanish into mostly-unwritten history.

While reading the Voyage, I was bewitched by these testimonies. It feels like catching vivid but fragmentary glimpses of the past, as if through a shaky old telescope. In this post, I'll share with you several excerpts to whet your appetite, but I can hope to do little more than that. Darwin's own descriptions are necessarily a sparse and reductive view into those cultures and times, and my selection reduces even more. This won't give you anything near a "full picture" of life in the Southern Hemisphere in the 1830's. But, if these glimpses interest you, do read the whole book! You might find yourself, like me, wanting to read even more sources about that historical period.

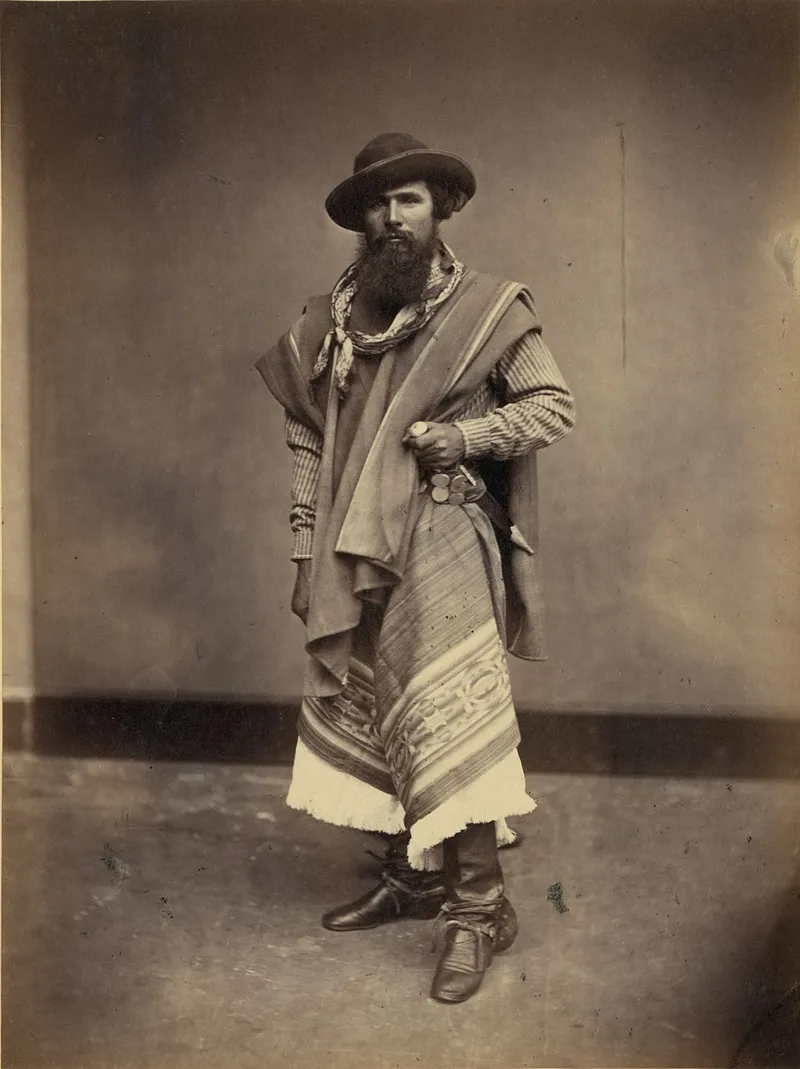

Argentina: Life on the Plains

The Beagle remained in Argentina for well over one year in total, and during that time Darwin was always roaming around. His scientific studies led him to travel long distances inland. Sometimes he was away from FitzRoy's ship for as long as two months straight. In August 1833, for example, the Beagle dropped him off at Río Negro and he traveled on horseback through the Argentinian plains with some gauchos (basically cowboys), through Bahía Blanca, across the Pampas to Buenos Aires, surveying rivers—he found several important fossils there—and collecting specimens until October that year. During that time, he often followed the ways of the gauchos, something the wealthy young Brit didn't dislike at all.

This was the first night which I passed under the open sky, with the gear of the recado [saddle] for my bed. There is high enjoyment in the independence of the Gaucho life—to be able at any moment to pull up your horse, and say, “Here we will pass the night.” The deathlike stillness of the plain, the dogs keeping watch, the gipsy-group of Gauchos making their beds round the fire, have left in my mind a strongly-marked picture of this first night, which will never be forgotten.

— Voyage of the Beagle (all quotes below from the same book unless otherwise stated)

Whenever possible, though, they would seek shelter in the local estancias, large cattle and horse ranches typical of the Argentine plains. Inevitably, he learned a lot about the peculiar ways of life of the locals.

I was confined for these two days to my bed by a headache. A good-natured old woman, who attended me, wished me to try many odd remedies. A common practice is, to bind an orange-leaf or a bit of black plaster to each temple: and a still more general plan is, to split a bean into halves, moisten them, and place one on each temple, where they will easily adhere. It is not thought proper ever to remove the beans or plaster, but to allow them to drop off, and sometimes, if a man, with patches on his head, is asked, what is the matter? he will answer, "I had a headache the day before yesterday."

The naturalist wrote about customs like that frequently and vividly.

Many of the remedies used by the people of the country are ludicrously strange, but too disgusting to be mentioned. One of the least nasty is to kill and cut open two puppies and bind them on each side of a broken limb. Little hairless dogs are in great request to sleep at the feet of invalids.

It sounds like the population density in those regions was quite low, and traveling through them wasn't easy—especially when transporting something with legs:

It is very difficult to drive animals across the plains; for if in the night a puma, or even a fox, approaches, nothing can prevent the horses dispersing in every direction; and a storm will have the same effect. A short time since, an officer left Buenos Ayres with five hundred horses, and when he arrived at the army he had under twenty.

Darwin had great respect for the gauchos, the true masters of that land, and for their skills with the lazo and bolas. Even when accounting for their roughness and laziness:

The Gauchos, or countrymen, are very superior to those who reside in the towns. The Gaucho is invariably most obliging, polite, and hospitable: I did not meet with even one instance of rudeness or inhospitality. He is modest, both respecting himself and country, but at the same time a spirited, bold fellow. On the other hand, many robberies are committed, and there is much bloodshed: the habit of constantly wearing the knife is the chief cause of the latter. It is lamentable to hear how many lives are lost in trifling quarrels. In fighting, each party tries to mark the face of his adversary by slashing his nose or eyes; as is often attested by deep and horrid-looking scars. Robberies are a natural consequence of universal gambling, much drinking, and extreme indolence. At Mercedes I asked two men why they did not work. One gravely said the days were too long; the other that he was too poor. The number of horses and the profusion of food are the destruction of all industry.

— From Darwin's Diary

General Rosas: Genocidal Crusades

Content warning: this section contains some gruesome bits.

Argentinian history has never been tranquil, but the period witnessed by Darwin was as violent as they get. In his 1833 excursion to Bahia Blanca, he met the troops of the infamous General Juan Manuel de Rosas in the act of exterminating all indigenous tribes daring enough to try defending their ancestral territories. Rosas was then already a prominent political and military figure, having (been) served as Governor of the Buenos Aires province until the previous year. Out of office, he had given himself the mission of "clearing the lands" from the "problem" of the "Indians". If successful, he would not only extend the reach of the Argentinian government, but also build the loyal following and reputation he needed to regain a position of power.

Rosas showed kindness toward Darwin, promptly granting him the travel permits he needed. Perhaps a bit naïve in his youth, the Englishman was swayed by the General's charisma, noting that he was very fair in his application of the law, and "also a perfect horseman".

By these means, and by conforming to the dress and habits of the Gauchos, he has obtained an unbounded popularity in the country, and in consequence a despotic power. I was assured by an English merchant, that a man who had murdered another, when arrested and questioned concerning his motive, answered, "He spoke disrespectfully of General Rosas, so I killed him." At the end of a week the murderer was at liberty. This doubtless was the act of the general's party, and not of the general himself.

At the time, Darwin believed Rosas to be "a man of an extraordinary character, and has a most predominant influence in the country, which it seems he will use to its prosperity and advancement." By the time of his book's 1845 edition, however, he had to add a footnote to this sentence: "This prophecy has turned out entirely and miserably wrong."

In fact, Rosas returned to power two years after meeting Darwin, and remained a totalitarian tyrant for almost two brutal decades. It was definitely a dark period of the country's history.

But let's return to 1833's genocidal campaign. Don Carlos was not as impressed with the troops as he was with their commander.

They passed the night here; and it was impossible to conceive anything more wild and savage than the scene of their bivouac. Some drank till they were intoxicated; others swallowed the steaming blood of the cattle slaughtered for their suppers, and then, being sick from drunkenness, they cast it up again, and were besmeared with filth and gore.

Considering what their job was, this kind of behavior is not surprising. Whenever Rosas' warriors were able to ambush an enemy camp, "the Indians, men, women, and children ... were nearly all taken or killed, for the soldiers sabre every man." In open battle, no mercy was contemplated:

One dying Indian seized with his teeth the thumb of his adversary, and allowed his own eye to be forced out sooner than relinquish his hold. Another, who was wounded, feigned death, keeping a knife ready to strike one more fatal blow. My informer said, when he was pursuing an Indian, the man cried out for mercy, at the same time that he was covertly loosing the bolas from his waist, meaning to whirl it round his head and so strike his pursuer. "I however struck him with my sabre to the ground, and then got off my horse, and cut his throat with my knife." This is a dark picture; but how much more shocking is the unquestionable fact, that all the women who appear above twenty years old are massacred in cold blood! When I exclaimed that this appeared rather inhuman, he answered, "Why, what can be done? they breed so!"

In some cases, local tribes chose to ally with him and sold him information about the other tribes, and sometimes even fought them directly.

The general, however, ... thinking that his friends may in a future day become his enemies, always places them in the front ranks, so that their numbers may be thinned.

Eventually, the voyage left the shores of Argentina, so that was all Darwin could witness. Fortunately, he notes in his book that "since leaving South America we have heard that this war of extermination completely failed."

Falklands: Atlantic Wild West

The Beagle visited the Falkland Islands twice over its 5-year journey, finding them in a very transitory state. Darwin summarizes in one paragraph the archipelago's whole history:

After the possession of these miserable islands had been contested by France, Spain, and England, they were left uninhabited. The government of Buenos Aires then sold them to a private individual, but likewise used them, as old Spain had done before, for a penal settlement. England claimed her right and seized them. The Englishman who was left in charge of the flag was consequently murdered. A British officer was next sent, unsupported by any power: and when we arrived, we found him in charge of a population, of which rather more than half were runaway rebels and murderers.

Captain FitzRoy was especially disappointed by the sorry state of the place. In his own volume of the Voyage, he writes:

A few half-ruined stone cottages; some straggling huts built of turf; two or three stove boats; some broken ground where gardens had been, and where a few cabbages or potatoes still grew; some sheep and goats; a few long-legged pigs; some horses and cows; with here and there a miserable-looking human being – were scattered over the fore-ground of a view which had dark clouds, ragged-topped hills, and a wild waste of moorland to fill up the distance.

The "unsupported" British officer had taken with him a handful of gauchos from the Argentinian mainland, as his only armed forces. But the gauchos didn't like it there. Again, FitzRoy:

The gauchos wished to leave the place, and return to the Plata, but as they were the only useful labourers on the islands, in fact, the only people on whom any dependance could be placed for a regular supply of fresh beef, I interested myself as much as possible to induce them to remain, and with partial success, for seven staid out of twelve.

Only months after the Beagle's first visit, an eight-person uprising killed several senior members of the settlement, thrusting the place into (teacup) chaos once again.

Apart from some fossils, a now-extinct species of fox, and some geological observations, there wasn't much of interest for Darwin in that "desolate" place. I found this story that he heard from a local tantalizing, though:

At the Falkland Islands, when the Spaniards murdered some of their own countrymen and all the Englishmen, a young friendly Spaniard was running away, when a great tall man, by name Luciano, came at full gallop after him, shouting to him to stop, and saying that he only wanted to speak to him. Just as the Spaniard was on the point of reaching the boat, Luciano threw the balls [bolas]: they struck him on the legs with such a jerk, as to throw him down and to render him for some time insensible. The man, after Luciano had had his talk, was allowed to escape.

Apart from showing the gaucho bolas in action, this passage isn't that historically important. But the curiosity is killing me: what did Luciano have to say so urgently to the Spaniard? Darwin never tells us, and this mystery seems to be forever lost to oblivion.

Chile and Peru: Forms of Peace

After spending a couple of years on the tempestuous eastern coast of South America, and after delivering the Fuegians to their home in Tierra del Fuego (see Ep. 3), HMS Beagle moved on to the more peaceful western coast, moving up and down the islands and cities of Chile and Peru. I've already quoted many passages from the Voyage about the natural wonders of the place, but his narrative also offers glimpses of the day-to-day life in those places.

These were not wealthy people—at least the non-Europeans. Commerce usually consisted in barter:

At Caylen [now Chaullin, part of the Chiloé Archipelago], the most southern island, the sailors bought with a stick of tobacco, of the value of three-halfpence, two fowls, one of which, the Indian stated, had skin between its toes, and turned out to be a fine duck; and with some cotton handkerchiefs, worth three shillings, three sheep and a large bunch of onions were procured.

Darwin also noted the clever practices of the local shepherds:

My companions were Mariano Gonzales, who had formerly accompanied me in Chile, and an "arriero," with his ten mules and a "madrina." The madrina (or godmother) is a most important personage: she is an old steady mare, with a little bell round her neck; and wherever she goes, the mules, like good children, follow her. The affection of these animals for their madrinas saves infinite trouble. If several large troops are turned into one field to graze, in the morning the muleteers have only to lead the madrinas a little apart, and tinkle their bells; and although there may be two or three hundred together, each mule immediately knows the bell of its own madrina, and comes to her. It is nearly impossible to lose an old mule; for if detained for several hours by force, she will, by the power of smell, like a dog, track out her companions, or rather the madrina, for, according to the muleteer, she is the chief object of affection.

The technique of using a mare to control mules was common across the world, but this was my first time reading about it. Mule psychology!

I said that the place was peaceful. I meant that in a relative sense: we'll see a large-scale exception at the end of this post; the other exception was crime and political instability. This tragicomical episode from Chapter XVI should give you an idea of the atmosphere in 1835 Peru:

A short time before, three French carpenters had broken open, during the same night, the two churches [in the town of Iquique, now part of Chile], and stolen all the plate: one of the robbers, however, subsequently confessed, and the plate was recovered. The convicts were sent to Arequipa, which though the capital of this province, is two hundred leagues distant, the government there thought it a pity to punish such useful workmen who could make all sorts of furniture; and accordingly liberated them. Things being in this state, the churches were again broken open, but this time the plate was not recovered. The inhabitants became dreadfully enraged, and declaring that none but heretics would thus "eat God Almighty," proceeded to torture some Englishmen, with the intention of afterwards shooting them. At last the authorities interfered, and peace was established.

Fortunately a happy ending there.

Pacific Life

The last major phase of the British voyage around the globe was the year or so spent in the islands of the Pacific and Oceania. Here, too, Darwin gives us far too many fascinating peeks into local customs and living conditions to cover fully in a blog post, but here is a medley.

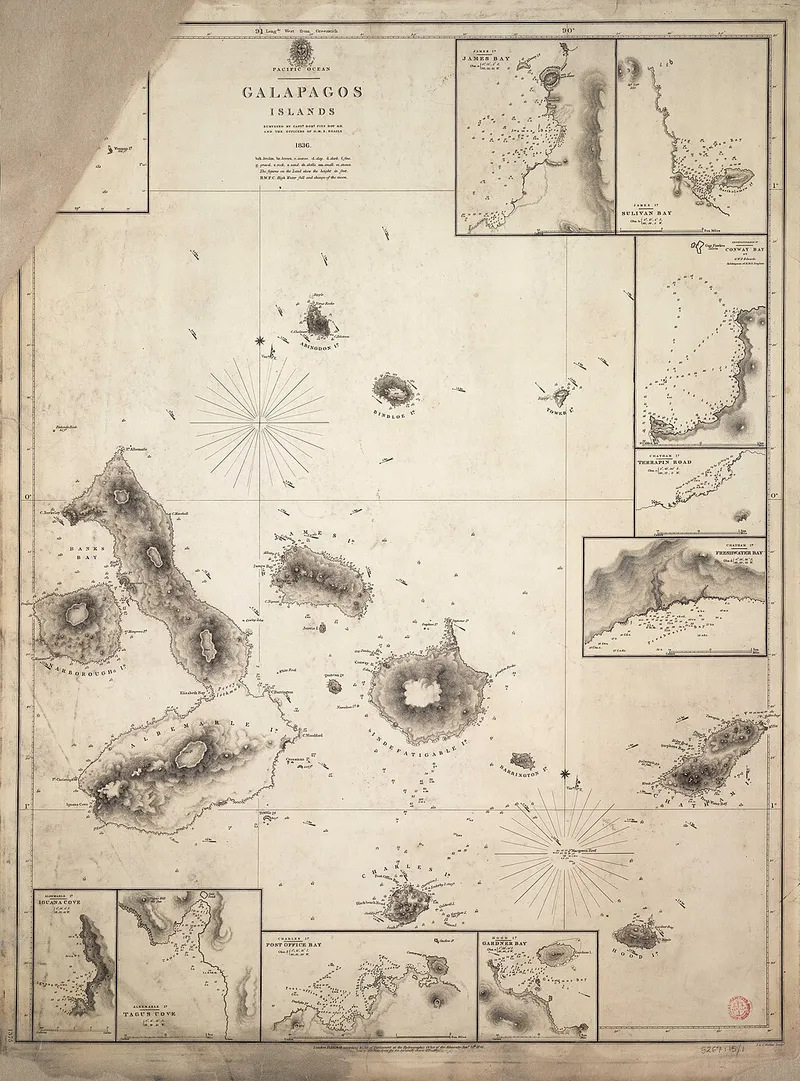

The Galapagos islands had literally barely been reached by mainland colonizers. Only three years before the Beagle's visit—after the ship had set sail from England!—Ecuador had claimed the islands for the first time and made them into a penal colony (a common fate for islands at the time). When FitzRoy's crew arrived in 1835, there was almost no European presence, only a handful of prisoners and a few huts. Life on the islands was simple and exploitative.

The inhabitants, although complaining of poverty, obtain, without much trouble, the means of subsistence. In the woods there are many wild pigs and goats; but the staple article of animal food is supplied by the tortoises. Their numbers have of course been greatly reduced in this island, but the people yet count on two days' hunting giving them food for the rest of the week. It is said that formerly single vessels have taken away as many as seven hundred, and that the ship's company of a frigate some years since brought down in one day two hundred tortoises to the beach.

The settlers (there were no natives) killed many more tortoises than would have been sustainable, which eventually led to the extinction of some of their species. They didn't always kill outright, though not out of any conservationist spirit:

The flesh of this animal is largely employed, both fresh and salted; and a beautifully clear oil is prepared from the fat. When a tortoise is caught, the man makes a slit in the skin near its tail, so as to see inside its body, whether the fat under the dorsal plate is thick. If it is not, the animal is liberated; and it is said to recover soon from this strange operation.

Tahiti, on the other hand, was rather densely populated, and its natives impressed Darwin more than any other group. Unfortunately, missionaries had been active in the islands for decades already, and had been largely successful in "civilizing" the Tahitians: they were Christian now, and quite familiar with the English language. Much of what the naturalist praised in them was about this high level of development, rather than their original ways (see Ep. 3 for more). Still, he described the decorations of the Tahitians' bodies in detail:

Most of the men are tattooed, and the ornaments follow the curvature of the body so gracefully, that they have a very elegant effect. One common pattern, varying in its details, is somewhat like the crown of a palm-tree. It springs from the central line of the back, and gracefully curls round both sides. The simile may be a fanciful one, but I thought the body of a man thus ornamented was like the trunk of a noble tree embraced by a delicate creeper.

Many of the elder people had their feet covered with small figures, so placed as to resemble a sock. This fashion, however, is partly gone by, and has been succeeded by others. Here, although fashion is far from immutable, every one must abide by that prevailing in his youth. An old man has thus his age for ever stamped on his body, and he cannot assume the airs of a young dandy. The women are tattooed in the same manner as the men, and very commonly on their fingers. One unbecoming fashion is now almost universal: namely, shaving the hair from the upper part of the head, in a circular form, so as to leave only an outer ring. The missionaries have tried to persuade the people to change this habit; but it is the fashion, and that is a sufficient answer at Tahiti, as well as at Paris.

We've already seen that Darwin did not much care for New Zealand: the area he saw—the Bay of Islands—was too plain, and the settlers too enterprising for his tastes. The aborigines also seemed less attractive and interesting to him compared to his beloved Tahitians. Nevertheless, he did manage to observe some traditional customs in the short nine days he was there. For example, I love this aboriginal greeting (we'll see if I can get it to catch on in Japan):

On coming near one of the huts I was much amused by seeing in due form the ceremony of rubbing, or, as it ought to be called, pressing noses. The women, on our first approach, began uttering something in a most dolorous voice; they then squatted themselves down and held up their faces; my companion standing over them, one after another, placed the bridge of his nose at right angles to theirs, and commenced pressing. This lasted rather longer than a cordial shake of the hand with us, and as we vary the force of the grasp of the hand in shaking, so do they in pressing.

Darwin also provides an important description of the funerary rites of those tribes.

The daughter of a chief, who was still a heathen, had died there five days before. The hovel in which she had expired had been burnt to the ground: her body, being enclosed between two small canoes, was placed upright on the ground, and protected by an enclosure bearing wooden images of their gods, and the whole was painted bright red, so as to be conspicuous from afar. Her gown was fastened to the coffin, and her hair being cut off was cast at its foot. The relatives of the family had torn the flesh of their arms, bodies, and faces, so that they were covered with clotted blood; and the old women looked most filthy, disgusting objects. On the following day some of the officers visited this place, and found the women still howling and cutting themselves.

The final stop in that corner of the world was Australia. Besides all the comments I've already shared about slavery and land theft—delivered with that same contradictory attitude, at once appreciative and condescending—he gives a description of an aboriginal festival:

When both tribes mingled in the dance, the ground trembled with the heaviness of their steps, and the air resounded with their wild cries. Every one appeared in high spirits, and the group of nearly naked figures, viewed by the light of the blazing fires, all moving in hideous harmony, formed a perfect display of a festival amongst the lowest barbarians.

Epochal Destruction

Darwin was no anthropologist (the discipline itself would not be properly established for another half a century), but I'm sure that his reports of the local peoples are valuable material for the real anthropologists that came after. by far the most impressive historical event he witnessed and recorded, though, was of a very different nature.

Without planning to, he provided a dreadful foreshadowing of what would happen later. It was February 1835, while the vessel explored the Chilean coast.

On the night of the 19th the volcano of Osorno was in action. At midnight the sentry observed something like a large star, which gradually increased in size till about three o'clock, when it presented a very magnificent spectacle. By the aid of a glass, dark objects, in constant succession, were seen, in the midst of a great glare of red light, to be thrown up and to fall down. The light was sufficient to cast on the water a long bright reflection. Large masses of molten matter seem very commonly to be cast out of the craters in this part of the Cordillera. I was assured that when the Corcovado is in eruption, great masses are projected upwards and are seen to burst in the air, assuming many fantastical forms, such as trees: their size must be immense, for they can be distinguished from the high land behind S. Carlos, which is no less than ninety-three miles from the Corcovado. In the morning the volcano became tranquil. ... I was surprised at hearing afterwards that Aconcagua in Chile, 480 miles northwards, was in action on the same night; and still more surprised to hear that the great eruption of Coseguina (2700 miles north of Aconcagua), accompanied by an earthquake felt over a 1000 miles, also occurred within six hours of this same time. This coincidence is the more remarkable, as Coseguina had been dormant for twenty-six years; and Aconcagua most rarely shows any signs of action. It is difficult even to conjecture whether this coincidence was accidental, or shows some subterranean connection.

There was no accepted explanation for volcanic eruptions at the time, but Darwin couldn't help but notice the coincidence and suspect that something of an enormous scale was involved. No one, however, anticipated what would happen the next day.

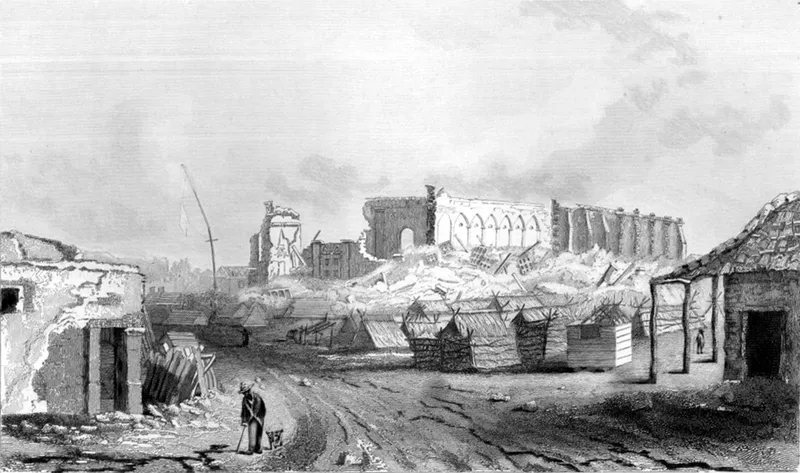

In the morning of February 20th, "the most severe earthquake experienced by the oldest inhabitant" hit the Chilean coast, centered near the city of Concepcion. The shake was felt over an area spanning almost 700 kilometers throughout the continent, and reached Darwin in Valdivia.

I happened to be on shore, and was lying down in the wood to rest myself. It came on suddenly, and lasted two minutes, but the time appeared much longer. The rocking of the ground was very sensible. ... A bad earthquake at once destroys our oldest associations: the earth, the very emblem of solidity, has moved beneath our feet like a thin crust over a fluid;—one second of time has created in the mind a strange idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would not have produced. In the forest, as a breeze moved the trees, I felt only the earth tremble, but saw no other effect.

(Side note: he undoubtedly used that "like a thin crust over a fluid" as a metaphor, without knowing how scientifically accurate he was!)

The Beagle was not far from the epicenter of the earthquake, and in a couple of weeks they reached Concepcion, the area of maximum devastation. A local who welcomed them there recounted

"That not a house in Concepcion or Talcahuano (the port) was standing; that seventy villages were destroyed; and that a great wave had almost washed away the ruins of Talcahuano." Of this latter statement I soon saw abundant proofs—the whole coast being strewed over with timber and furniture as if a thousand ships had been wrecked. Besides chairs, tables, book-shelves, etc., in great numbers, there were several roofs of cottages, which had been transported almost whole. The storehouses at Talcahuano had been burst open, and great bags of cotton, yerba, and other valuable merchandise were scattered on the shore.

Darwin notes the geological effects of the cataclysm, how "the ground in many parts was fissured" and "the superficial parts of some narrow ridges were as completely shivered as if they had been blasted by gunpowder." But the locals had more intense stories to tell.

The first shock was very sudden. The mayor-domo at Quiriquina told me, that the first notice he received of it, was finding both the horse he rode and himself, rolling together on the ground. Rising up, he was again thrown down. He also told me that some cows which were standing on the steep side of the island were rolled into the sea.

As shock succeeded shock, at the interval of a few minutes, no one dared approach the shattered ruins, and no one knew whether his dearest friends and relations were not perishing from the want of help. Those who had saved any property were obliged to keep a constant watch, for thieves prowled about, and at each little trembling of the ground, with one hand they beat their breasts and cried "misericordia!" and then with the other filched what they could from the ruins. The thatched roofs fell over the fires, and flames burst forth in all parts. Hundreds knew themselves ruined, and few had the means of providing food for the day.

Ever the science communicator, Darwin uses familiar terms in the Voyage to convey the horror and destruction involved:

Earthquakes alone are sufficient to destroy the prosperity of any country. If beneath England the now inert subterranean forces should exert those powers ..., how completely would the entire condition of the country be changed! What would become of the lofty houses, thickly packed cities, great manufactories, the beautiful public and private edifices? ... England would at once be bankrupt; all papers, records, and accounts would from that moment be lost. ... The hand of violence and rapine would remain uncontrolled. In every large town famine would go forth, pestilence and death following in its train.

He also compares the area afflicted in those few days to places in Europe, which is impressive even today:

It will give a better idea of the scale of these phenomena, if ... we suppose them to have taken place at corresponding distances in Europe:—then would the land from the North Sea to the Mediterranean have been violently shaken, and at the same instant of time a large tract of the eastern coast of England would have been permanently elevated, together with some outlying islands,—a train of volcanos on the coast of Holland would have burst forth in action, and an eruption taken place at the bottom of the sea, near the northern extremity of Ireland—and lastly, the ancient vents of Auvergne, Cantal, and Mont d'Or would each have sent up to the sky a dark column of smoke, and have long remained in fierce action. Two years and three-quarters afterwards, France, from its centre to the English Channel, would have been again desolated by an earthquake, and an island permanently upraised in the Mediterranean.

Today, Darwin's direct report of the Concepcion earthquake of 1835 is considered highly valuable both as a historical document and as scientific data for seismological studies. The Beagle was well equipped to take accurate observations of the local geography, and they measured exactly how much the land had been uplifted (roughly 3 meters in the island of Santa Maria). Their observations became useful material for an early understanding of tsunamis, and helped improve predictions of future earthquakes as lately as 2009.

The Concepcion area sees major earthquakes like that only once every century or so—previous occurrences were in 1570, 1657, 1751, and the next one would hit only in 1939. It was an incredible coincidence that such a competent and prepared crew as FitzRoy's, and such an articulate chronicler as Charles Darwin, were in the right place at the right time to preserve that memory for posterity. The same is true for all those other testimonies of peoples and places—treasures they kindly brought back from their great circumnavigation of the world. ●

Next, the last episode: In His Own Words Ep. 5 - Darwin El Naturalista

Cover image:

Volcano Osorno, Voyage of the Beagle