Darwin El Naturalista

In His Own Words (Episode 5)

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

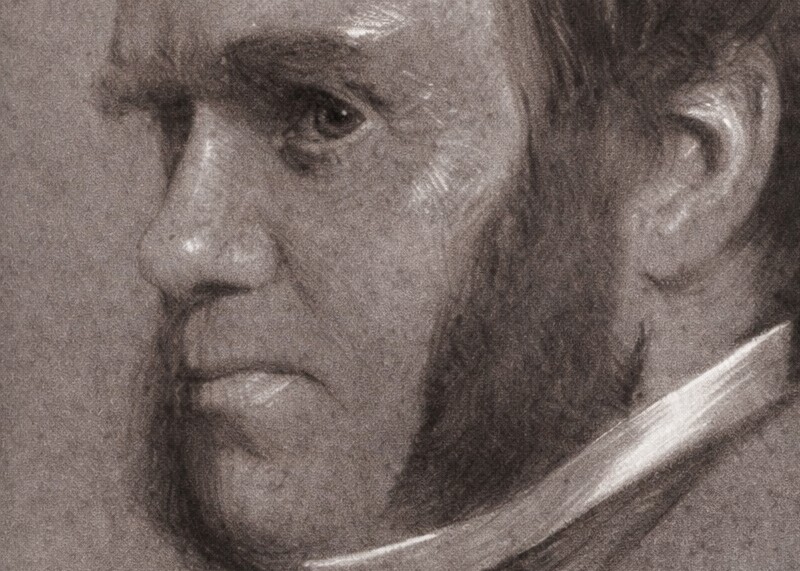

Cover image:

Portrait of Charles Darwin by Samuel Laurence (1853)

This is the final episode in the series of curated quote collections "Darwin in His Own Words".

- Darwin the Fun-Loving Young Fellow

- Darwin the Voyager

- Darwin the Man of His Times

- Darwin the Witness

- Darwin El Naturalista

At last, it's time to talk about young Charles Darwin's scientific side during his voyage on the Beagle (in his own words, of course). To be honest, though, so much has been written already about the origin his Origin (pun detected) that it would be boring to repeat the same old stuff. I want to share with you the kind of quotes that don't typically get paraphrased in textbooks and epitaphs. The rest is history, so this post is about the non-history part. Not the widely known history, at least.

What you'll find, in this slice of the book, almost-there-but-not-quite ideas. My main point is that Darwin—or El Naturalista Don Carlos, as his passport identified him—was already doing something right even in his early twenties, decades before he announced his theory of evolution by natural selection. You can see it in what he pays attention to, and you can see it in the questions that torment his youthful brain. From those, I think, you can glean all you need to understand how he managed to become what he later became.

Rocks and Shifting Earth

Darwin was recruited in Captain FitzRoy's crew as an all-around "naturalist". His mentor and protector Prof. John Stevens Henslow recommended him for the position, informing him of this helpful job description: "collecting, observing, & noting anything worthy to be noted in Natural History." The sciences were not so strictly separated at the time, so Darwin had learned the basics of most disciplines.

But, even then, everyone had a favorite discipline, and so did Darwin. When he boarded the ship in December 1831, he probably saw himself, first and foremost as... a geologist.

Today we associate him with biology, but the love for wild flora and fauna was more of a hobby to him at the time. He collected beetles, shot birds, and liked to take long walks in the woods, and that was more or less it. Geology, on the other hand, must have looked like the most promising path forward for his uncertain career. Just before receiving his life-changing invitation from FitzRoy, he had been assisting a professor on a month-long field trip to study the rock formations and geological strata of North Wales. He learned useful skills in this survey, and his notes at the time suggest that he was especially eager to study the hell out of those South American rocks. That he would learn more about how Life works than anyone before him may not have crossed his mind.

Darwin did stick to his resolution, and duly surveyed the mountains and mineral formations of every area he visited over the five-year voyage. But he did not limit himself to describing what he saw. He interpreted and, crucially, he confirmed.

Daily it is forced home on the mind of the geologist that nothing, not even the wind that blows, is so unstable as the level of the crust of this earth.

— Voyage of the Beagle (all quotes below from the same book unless otherwise stated)

A sentence like this may sound ordinary today, but it was quite unorthodox in his day. Darwin had been struck by Charles Lyell's controversial new theory of how the Earth's surface came to be as it is: not with sudden catastrophes that lifted mountains and tore canyons across the land once and for all, as was thought at the time, but by very slow and gradual changes. Where the geological orthodoxy believed that, once formed, all features of the land remained otherwise static, Lyell showed ample evidence that most of it had happened—was still happening—through continuous, "uniform" forces.

Young Darwin was won over by Lyell's uniformitarianism well before it became widely accepted among the "respectable" scholars. He made Lyell's framing his own even before Lyell was finished publishing his series of books on the topic.

It's not that he didn't feel the tension between intuition and scientific evidence, though:

As often as I have seen beds of mud, sand, and shingle, accumulated to the thickness of many thousand feet, I have felt inclined to exclaim that causes, such as the present rivers and the present beaches, could never have ground down and produced such masses. But, on the other hand, when listening to the rattling noise of these torrents, and calling to mind that whole races of animals have passed away from the face of the earth, and that during this whole period, night and day, these stones have gone rattling onwards in their course, I have thought to myself, can any mountains, any continent, withstand such waste?

This is what a good scientist must do: neither ignoring nor blindly following his first instinct, Darwin takes note of it and goes on to collect more data. He knows that the scientific method, and not any jump to conclusions, is the shortest path to a potential resolution of that tension.

Each framing is a lens capable of showing you the world in a different way, so this early bet on a mostly-correct new theory by Lyell was a major win for Darwin. In a sense, it made him the first scientist ever to look at the geology of South America and Oceania from a modern perspective.

So what? His contributions to geology have been eclipsed by the success of his theory of evolution. Ironically, though, his progressive view of geology played a major role in the development of his biological theory.

Predictions and Discoveries

Although researching rocks and minerals seemed like his career of choice, Darwin was diligent enough to also study the living things of every place he visited. In total, he brought back to Britain 1529 specimens in bottled spirits and 3907 dried specimens of plants and animals, including dozens of new species of birds, fish, and insects. These contributions were clearly appreciated by his fellow scholars, but I think they were a bit less sensational than they might sound today. South America hadn't been thoroughly explored by scientists yet, and even today it is full of undiscovered species, so it wasn't too hard to stumble on yet-uncataloged creatures.

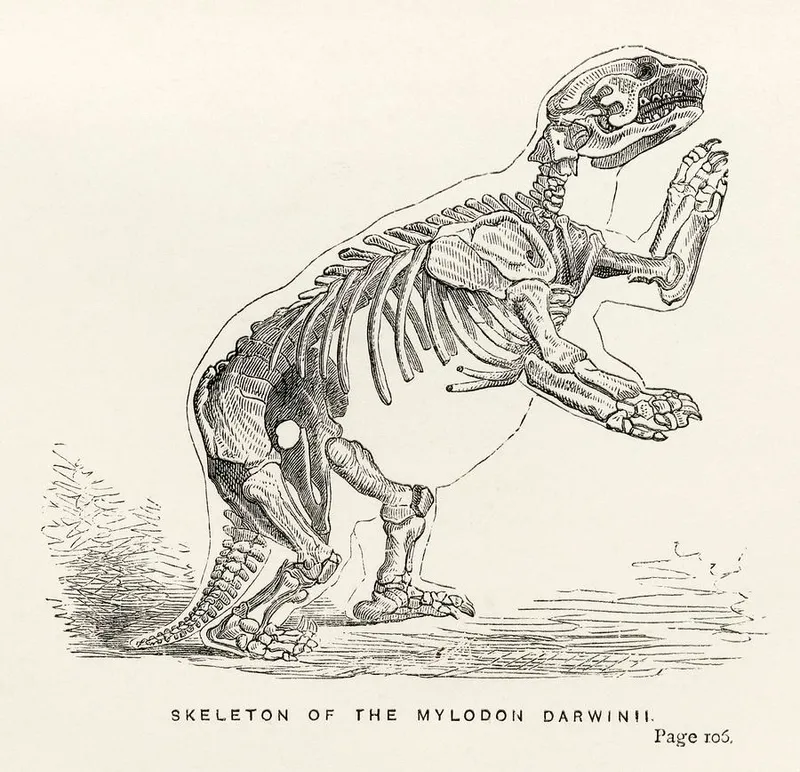

More important (though still not earth-shattering, I think) was his discovery of long-extinct megafauna fossils.

October 1st.—We started by moonlight and arrived at the Rio Tercero by sunrise. ... I stayed here the greater part of the day, searching for fossil bones. Besides a perfect tooth of the Toxodon, and many scattered bones, I found two immense skeletons near each other, projecting in bold relief from the perpendicular cliff of the Parana. They were, however, so completely decayed, that I could only bring away small fragments of one of the great molar teeth; but these are sufficient to show that the remains belonged to a Mastodon.

He unearthed bones of ancient relatives of horses, giant sloths, and other large mammals unlike any alive in his time. Overall, these findings created more questions than they answered, but they were immediately useful for at least one thing: they put the mystery of the extinction of species on the forefront of Darwin's mind. They also forced him to puzzle over the peculiar ways these animals were distributed across the world:

As so many species, both living and extinct, of these same genera inhabit and have inhabited the Old World, it seems most probable that the North American elephants, mastodons, horse, and hollow-horned ruminants migrated, on land since submerged near Behring’s Straits, from Siberia into North America, and thence, on land since submerged in the West Indies, into South America, where for a time they mingled with the forms characteristic of that southern continent, and have since become extinct.

This prediction was surprisingly accurate. Well, he did get the details of the direction of the migrations wrong (for example, today we know that horses originated in North America and moved out of it via the Bering Strait), but the idea that temporary land bridges could explain how species redistributed themselves was quite novel—a fruit of his adoption of Lyell's framing of ever-shifting landforms.

On the more strictly geological side of things, Darwin was not afraid to advance bold ideas about how mountains form:

From many reasons, I believe that the frequent quakings of the earth on this line of coast are caused by the rending of the strata, necessarily consequent on the tension of the land when upraised, and their injection by fluidified rock. This rending and injection would, if repeated often enough ... form a chain of hills

Again, the details weren't exactly right (magma injections were an effect of plate tectonics, not a cause in themselves), but he was doing pretty radical work all the same. Others had proposed a link between earthquakes, volcanoes, and orogeny (mountain formation) before, but Darwin was the first to provide direct and compelling evidence for it. He made a connection between his observations of the Concepción 1835 earthquake (Ep. 4) and its aftermath, where the Beagle's surveyors measured land uplift of up to 3 meters, and his discovery of marine fossils high up in the Andes; from these, he correctly concluded that, given enough time, a sequence of events like that could gradually have produced the majestic mountain ranges of the region. Again, Lyell's new theory at work, merely a couple of years after its publication.

But Darwin's biggest scientific discovery in the short term, brilliant enough to earn him a strong reputation long before his other, bigger theory, happened in the latter half of his voyage.

For some time, he had been curious about those bizarre shapes formed by corals in the tropical seas:

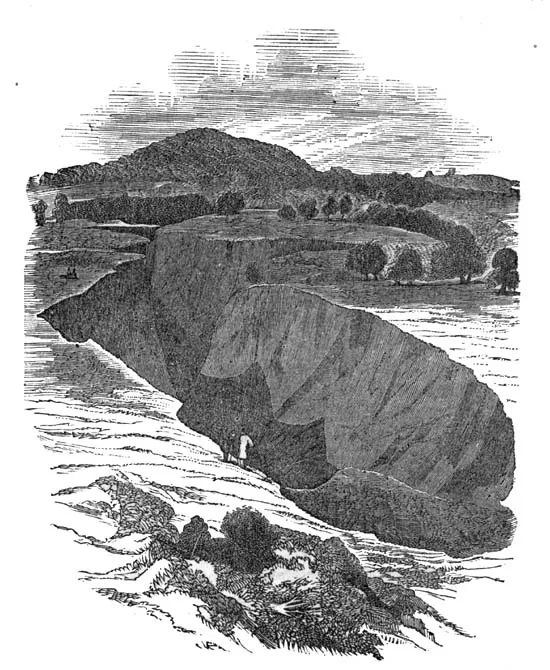

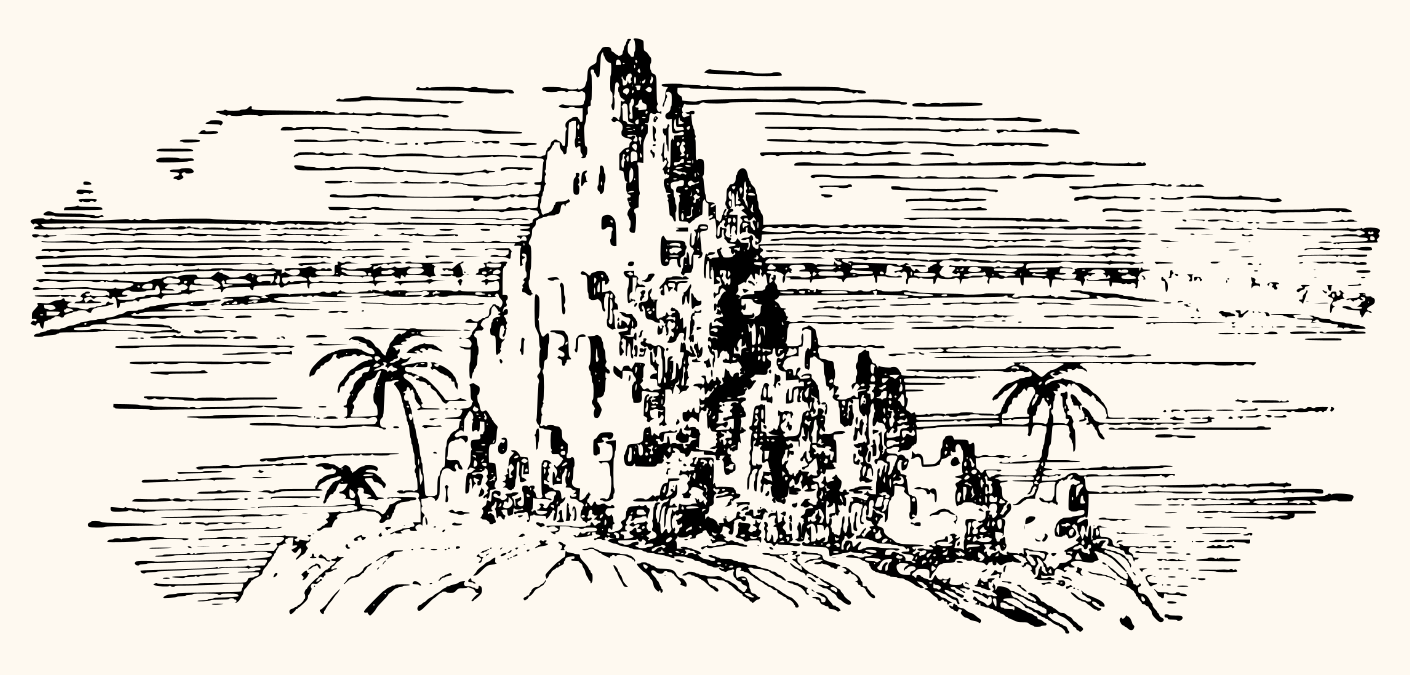

It is remarkable how little attention has been paid to encircling barrier-reefs; yet they are truly wonderful structures. The accompanying sketch represents part of the barrier encircling the island of Bolabola in the Pacific, as seen from one of the central peaks.

... Usually a snow-white line of great breakers, with only here and there a single low islet crowned with cocoa-nut trees, divides the dark heaving waters of the ocean from the light-green expanse of the lagoon-channel.

Darwin knew, as did his contemporaries, that those rings were made by corals, but no one knew the mechanism behind those strange patterns:

What has caused these reefs to spring up at such great distances from the shores of the included islands? It cannot be that the corals will not grow close to the land.

And yet the same pattern pops up over and over in the oceans of the world (they are examples of what I call Water Lilies). Darwin was the first to propose a model that was both convincing and supported by his empirical observations. In simple terms, they form when islands slowly sink over geological ages: the corals initially form close to the central island's shore, but as their reefs are dragged down by the rocky base, they build upward in their drive to remain close to the surface of the sea. In this way, the reef builds on top of itself and retains its original diameter, even while the central island's diameter shrinks.

This theory was both correct and original, and became his first scientific monograph after his return to England. He cleverly built on top of Lyell's ideas of gradual geological change to explain something about living creatures: almost a trademark move for him at this point.

The Voyage is full to the brim with Darwin's open questions and his hypothetical answers. A large number of them turned out to be wrong, of course, but several were surprisingly accurate and ahead of their time. How could a green twentysomething-year-old fresh out of college be so good at theorizing, and so often right?

I think the answer is clear: he was not afraid to make connections between fields that at the time seemed utterly unrelated. His conjectures about megafauna migrations and coral reefs, for example, were good conjectures thanks to his putting together geological ideas with data about animal behaviors.

Unbounded Curiosity

I don't want to overstate Darwin's direct discoveries during those years of travel. He didn't make that many discoveries, and he didn't change the world with them anyway (with the one obvious exception). In the grand scheme of things, those results were somewhat impressive, but not super important.

What I found most interesting, while reading his book, was not the number of correct theories he formulated, but the number of great questions he posed. The Voyage is thickly sprinkled with countless expressions of its author's curiosity about the amazing kaleidoscope of natural phenomena he witnessed.

I was often interested by watching the clouds, which, rolling in from seaward, formed a bank just beneath the highest point of the Corcovado. ... Mr. Daniell has observed, in his meteorological essays, that a cloud sometimes appears fixed on a mountain summit, while the wind continues to blow over it. The same phenomenon here presented a slightly different appearance. In this case the cloud was clearly seen to curl over, and rapidly pass by the summit, and yet was neither diminished nor increased in size.

Besides all the wonders I quoted back in Episode 2, Darwin also wondered about the lifecycle of worms living in saline mud ("what becomes of these worms when, during the long summer, the surface is hardened into a solid layer of salt?"), about the self-organization of krill spawn into long red streaks in the sea ("how do the various bodies which form the bands with defined edges keep together? ... what causes the length and narrowness of the bands?"), about the fossilization of trees ("how surprising it is that every atom of the woody matter ... should have been removed and replaced by silex so perfectly that each vessel and pore is preserved!"), about the habits of birds and reptiles, the distribution and differences between species, the meaning of geological layers, and too many more things to attempt a full list.

I need to make a little detour: out of the questions Darwin posed to himself, I was most struck by those about diseases. I knew that germ theory would only become widely accepted a few decades after the Beagle's trip, so of course I should have expected nothing else, but quotes like these still managed to bewilder me:

In all seasons, both inhabitants and foreigners suffer from severe attacks of ague. This disease is common on the whole coast of Peru, but is unknown in the interior. The attacks of illness which arise from miasma never fail to appear most mysterious.

Why does miasma just "pop up" here and not there? Also:

The plain round the outskirts of Callao is sparingly covered with a coarse grass, and in some parts there are a few stagnant, though very small, pools of water. The miasma, in all probability, arises from these ... Miasma is not always produced by a luxuriant vegetation with an ardent climate;

and

From these facts it would almost appear as if the effluvium of one set of men shut up for some time together was poisonous when inhaled by others; and possibly more so, if the men be of different races.

Reading these after all those other clever theories, it finally dawned on me with full force the fact that, oh boy, they had no idea! And yet they were so close:

Mysterious as this circumstance appears to be, it is not more surprising than that the body of one's fellow-creature, directly after death, and before putrefaction has commenced, should often be of so deleterious a quality that the mere puncture from an instrument used in its dissection should prove fatal.

Premonitions

You probably remember Darwin's Galapagos finches, each with a slightly different beak adapted to a different island in the archipelago. The story goes that those birds were what got him started with his big Origin of Species project. Well, the story was a bit more nuanced than that. The naturalist had been collecting, and noticing, all the pieces necessary for his theory over the course of several years.

The Voyage is an unwitting documentary on how his most consequential ideas slowly coalesced from their primordial soup, despite the fact that he still hadn't figured the theory out at the time of the chronicle's publication.

First, to avoid some common misconceptions, let me summarize in a paragraph where Darwin was starting from: the dominant theory about species was that somehow they were created—by God, presumably—all at once a few thousand years ago, and remained unchanged after that. But some scholars had been discussing for a while the idea of evolution, or variation of species (e.g. Lamarck and Charles' own grandfather Erasmus Darwin). Also, the facts that some species went extinct and others could "colonize" new regions were, by the 1830s, hard to refute. Lyell was now championing the idea that the world is much older than initially thought, and that it never ceased transforming. Finally, Humboldt and others had noted that animal and plant species always distribute themselves in specific parts of the world where they are well-adapted to the challenges of the local environment.

In other words, while the idea of evolution was still highly controversial, the old creationist theory was already showing deep, deep cracks. The problem was that no one had figured out how evolution might possibly work, and few even dared trying.

Darwin himself, for all his youthful progressivism, didn't try to question the creationist view in the Voyage. In an amusing "Darwin before Darwin" moment, he notes that different species exist on the two sides of the Cordillera, but waves it away noncommittally:

These mountains have existed as a great barrier since the present races of animals have appeared; and therefore, unless we suppose the same species to have been created in two different places, we ought not to expect any closer similarity between the organic beings on the opposite sides of the Andes than on the opposite shores of the ocean.

And yet, his inexhaustible curiosity and attention to detail made him... notice things.

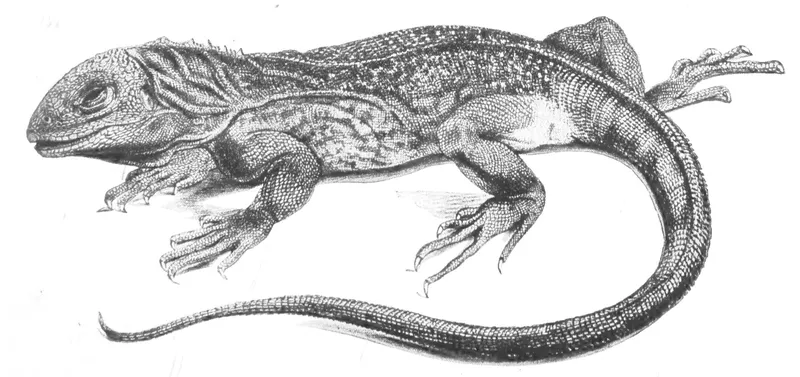

He noticed first hand how well organisms seem to be adapted to the places they live in. For example, about the Galapagos lizards he notes:

Their limbs and strong claws are admirably adapted for crawling over the rugged and fissured masses of lava which everywhere form the coast.

He also noticed that animals adapt differently to different climates:

The lowest point to which the thermometer fell was 41.5° ... Yet with this high temperature, almost every beetle, several genera of spiders, snails, and land-shells, toads and lizards, were all lying torpid beneath stones. But we have seen that at Bahia Blanca, which is four degrees southward, and therefore with a climate only a very little colder, this same temperature, with a rather less extreme heat, was sufficient to awake all orders of animated beings. This shows how nicely the stimulus required to arouse hybernating animals is governed by the usual climate of the district, and not by the absolute heat.

That is to say, even relatively similar animals in relatively close regions will behave differently depending on the temperatures typical of where they live.

If that weren't enough, he noticed how species adapt to each other, i.e. to what today we would call their ecosystems.

For example, he found that those marine lizards in the Galapagos were very agile in the water and almost defenseless on land, and yet they very much preferred staying dry even when a British guy kept tormenting them up there (remember Ep. 1?). About this paradox he notes:

Perhaps this singular piece of apparent stupidity may be accounted for by the circumstance that this reptile has no enemy whatever on shore, whereas at sea it must often fall a prey to the numerous sharks. Hence, probably, urged by a fixed and hereditary instinct that the shore is its place of safety, whatever the emergency may be, it there takes refuge.

Indeed! Another time, after describing the remarkable ability of a crab to split open a rock-hard cononut, he adds,

I think this is as curious a case of instinct as ever I heard of, and likewise of adaptation in structure between two objects apparently so remote from each other in the scheme of nature as a crab and a cocoa-nut tree.

Until this point, okay—perhaps God simply created all these creatures with these adaptations from the start. But other things caught Darwin's attention, things that weren't so easily reconciled with creationism.

For one thing, ecosystems themselves are always changing! Emus and kangaroos were being decimated in Australia, for example, and something similar had happened in Argentina:

According to the principles so well laid down by Mr. Lyell, few countries have undergone more remarkable changes, since the year 1535, when the first colonist of La Plata landed with seventy-two horses. The countless herds of horses, cattle, and sheep, not only have altered the whole aspect of the vegetation, but they have almost banished the guanaco, deer, and ostrich. Numberless other changes must likewise have taken place.

And what about this parallel between humans conquering other humans and the what happens between different animals?

The varieties of man seem to act on each other in the same way as different species of animals—the stronger always extirpating the weaker.

Call it "survival of the strongest", if not yet the fittest.

Finally, and for good measure, the Voyage shows Darwin reasoning rather sharply about inheritance of behaviors. Remember how he would casually kill ultra-naive birds "with a switch, and sometimes, as I myself tried, with a cap or hat" (Ep. 1)? Well, he didn't do that for fun, really. He was learning some very important truths about nature:

From these several facts we may, I think, conclude, first, that the wildness of birds with regard to man is a particular instinct directed against him, and not dependent upon any general degree of caution arising from other sources of danger; secondly, that it is not acquired by individual birds in a short time, even when much persecuted; but that in the course of successive generations it becomes hereditary.

All these "noticings", to me, paint an interesting picture. Almost all of the pieces were right there under his nose, dots almost amusingly easy to connect for us readers of the future. Unfortunately, he didn't get it yet at the time of the Voyage (he hadn't read about Malthus' idea of the eternal struggle for limited resources), and could only conclude that his observations might hopefully "assist in revealing the grand scheme, common to the present and past ages, on which organised beings have been created."

He didn't get it, but he was deeply puzzled by all of it. The finches, and the careful re-examination of his specimens back home, were not the spark that gave him the idea. They were the last drop in a bucket already full of questions.

Who Was He?

To recap, reading Darwin's innocent debut publication reveals a man endlessly curious about everything around him; a man eager to make new connections between different fields; a still-nameless scientist brave enough to advance hypotheses considered almost heretical by most of his peers; a man capable of acknowledging the tensions between compelling ideas, and of refusing to be satisfied with them; and a man with the patience and drive to pursue the truth, even when he knows it could be unpleasant, as demonstrated by his "golden rule"

Whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from the memory than favourable ones. Owing to this habit, very few objections were raised against my views which I had not at least noticed and attempted to answer.

— Autobiography

In short, he was already a great scientist before even making a single discovery.

As an extra gift, a reading of The Voyage of the Beagle will also show you a fun-loving, adventurous, spoiled, in some ways narrow-minded, frequently wonder-struck, and observant young man. So much gold in just one book! And, if you've read this far, you know what to read next. ●

The End

Cover image:

Portrait of Charles Darwin by Samuel Laurence (1853)