Darwin the Voyager

In His Own Words (Episode 2)

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

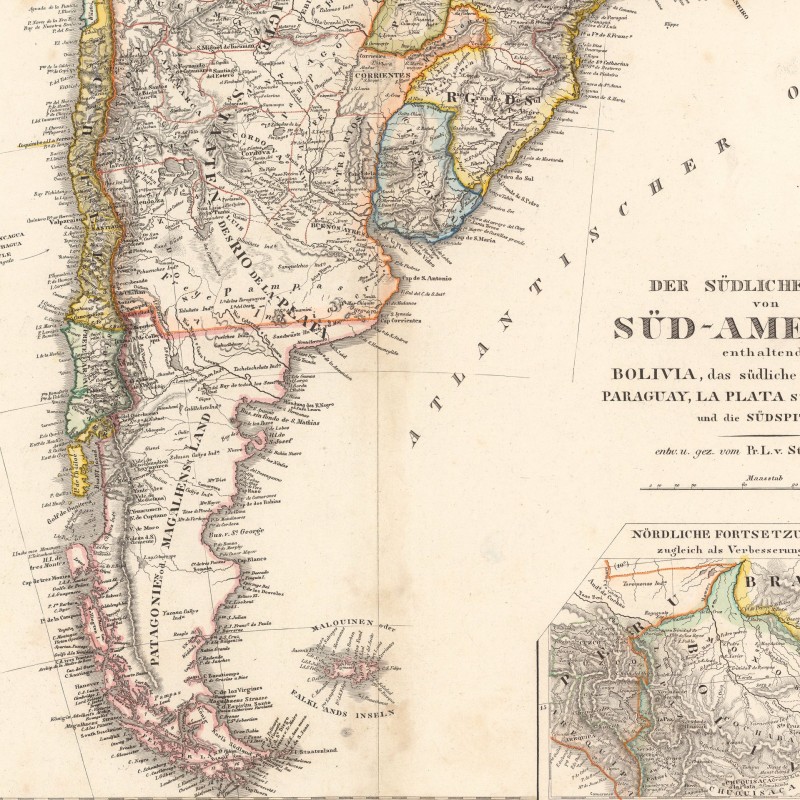

Cover image:

Map: Der sudliche Theil von Sud-America, Adolf Stieler, 1831

This is the second episode in the series of curated quote collections "Darwin in His Own Words".

- Darwin the Fun-Loving Young Fellow

- Darwin the Voyager

- Darwin the Man of His Times

- Darwin the Witness

- Darwin El Naturalista

Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle was more than a series of fun episodes. It was, first and foremost, a scientific expedition, and this job occupied Darwin full-time for his five years of travel (minus the many days he had to spend lying down sick). But the Voyage is also exactly what it says on the can: the retelling of a grand journey around the globe, passing through some of the wildest and most remote places then known to humankind. In fact, remove all the scientific descriptions and erudite disquisitions from the book and you'll basically have an adventure diary. This is what I want to focus on with this week's quotes.

That great journey deeply affected Darwin for the rest of his life. Throughout his narrative, the emotional impact of what he saw, what he experienced, and the people he interacted with seems to push the boundaries of what he was able to express in words. He would later recollect those times with fondness. In a letter to FitzRoy in 1840, he wrote that he often had "the most vivid and delightful pictures of what I saw on board the Beagle pass before my eyes.– These recollections & what I learnt in Natural History I would not exchange for twice ten thousand a year." (Clearly, Charles Darwin didn't have aphantasia.)

What did he see out there, then?

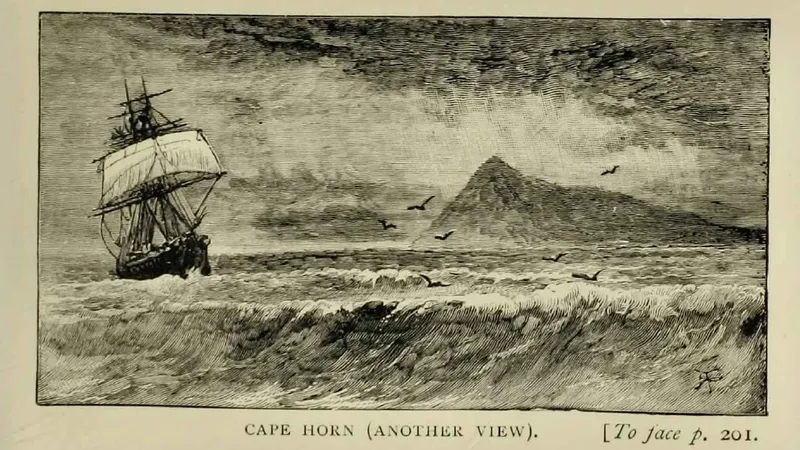

Adventure

You can't have, today, the kind of adventure Darwin experienced back then: going to places that take weeks of wearisome sea or land travel to reach, to grand and treacherous sites that have been barely touched by human feet, let alone written about for others to read.

In vain we tried to gain the summit: the forest was so impenetrable, that no one who has not beheld it can imagine so entangled a mass of dying and dead trunks. I am sure that often, for more than ten minutes together, our feet never touched the ground, and we were frequently ten or fifteen feet above it, so that the seamen as a joke called out the soundings. At other times we crept one after another, on our hands and knees, under the rotten trunks.

— Voyage of the Beagle (all quotes below from the same book)

In our descent we followed the line of ridges; these were exceedingly narrow, and for considerable lengths steep as a ladder; but all clothed with vegetation. The extreme care necessary in poising each step rendered the walk fatiguing. I did not cease to wonder at these ravines and precipices: when viewing the country from one of the knife-edged ridges, the point of support was so small that the effect was nearly the same as it must be from a balloon.

Many of those remarkable places are still there. You can go there if you want to. But it wouldn't be the same thing. In the 1830's, there were no tourists or geared-up wilderness aficionados crowding those areas. There were no online guides, no rescue forces, no safety guidelines. Most of those places weren't even properly charted when el naturalista Don Carlos was there. We can only imagine what it must have felt like.

After two decades of reading about Nature, Darwin was finally connecting with it at a deeper level.

It has been said that the love of the chase is an inherent delight in man—a relic of an instinctive passion. If so, I am sure the pleasure of living in the open air, with the sky for a roof and the ground for a table, is part of the same feeling; it is the savage returning to his wild and native habits. I always look back to our boat cruises, and my land journeys, when through unfrequented countries, with an extreme delight, which no scenes of civilisation could have created.

There are many earnest snippets like this scattered throughout the Voyage—short passages that hide within them the force and beauty of wilderness. But Darwin was also capable of weaving mystery and storytelling into his descriptions.

One day we accompanied a party of the Spaniards in their whale-boat to a salina, or lake from which salt is procured. ... The water is only three or four inches deep and rests on a layer of beautifully crystallised, white salt. The lake is quite circular, and is fringed with a border of bright green succulent plants; the almost precipitous walls of the crater are clothed with wood, so that the scene was altogether both picturesque and curious. A few years since the sailors belonging to a sealing-vessel murdered their captain in this quiet spot; and we saw his skull lying among the bushes.

Why did the sailors murder their captain? What dreadful scenes unfolded in that untamed landscape? We are left to wonder.

Other times the story does find its resolution, like in the episode of the mysterious abandoned camp:

A strong desire is always felt to ascertain whether any human being has previously visited an unfrequented spot. A bit of wood with a nail in it is picked up and studied as if it were covered with hieroglyphics. Possessed with this feeling, I was much interested by finding, on a wild part of the coast, a bed made of grass beneath a ledge of rock. Close by it there had been a fire, and the man had used an axe. The fire, bed, and situation showed the dexterity of an Indian; but he could scarcely have been an Indian, for the race is in this part extinct, owing to the Catholic desire of making at one blow Christians and Slaves.

Who might have slept here, and why? The answer comes unexpectedly in the next day's log:

In the evening another harbour was discovered, where we anchored. Directly afterwards a man was seen waving his shirt, and a boat was sent which brought back two seamen. A party of six had run away from an American whaling vessel, and had landed a little to the southward in a boat, which was shortly afterwards knocked to pieces by the surf. They had now been wandering up and down the coast for fifteen months, without knowing which way to go, or where they were. What a singular piece of good fortune it was that this harbour was now discovered! Had it not been for this one chance, they might have wandered till they had grown old men, and at last have perished on this wild coast. Their sufferings had been very great, and one of their party had lost his life by falling from the cliffs. They were sometimes obliged to separate in search of food, and this explained the bed of the solitary man.

Some of the situations in Darwin's chronicle are downright surreal. Upside-down frozen horse statues? He's got you covered.

In the valleys there were several broad fields of perpetual snow. These frozen masses, during the process of thawing, had in some parts been converted into pinnacles or columns ... On one of these columns of ice a frozen horse was sticking as on a pedestal, but with its hind legs straight up in the air. The animal, I suppose, must have fallen with its head downward into a hole, when the snow was continuous, and afterwards the surrounding parts must have been removed by the thaw.

There was also a time in which a living force of nature blotted out the sun and reddened the fields:

Shortly before we arrived at this place we observed to the south a ragged cloud of a dark reddish-brown colour. At first we thought that it was smoke from some great fire on the plains; but we soon found that it was a swarm of locusts. They were flying northward; and with the aid of a light breeze, they overtook us at a rate of ten or fifteen miles an hour. The main body filled the air from a height of twenty feet to that, as it appeared, of two or three thousand above the ground; "and the sound of their wings was as the sound of chariots of many horses running to battle:" or rather, I should say, like a strong breeze passing through the rigging of a ship. The sky, seen through the advanced guard, appeared like a mezzotinto engraving, but the main body was impervious to sight; they were not, however, so thick together, but that they could escape a stick waved backwards and forwards. When they alighted, they were more numerous than the leaves in the field, and the surface became reddish instead of being green: the swarm having once alighted, the individuals flew from side to side in all directions.

Contact With the Locals

The natural world was Darwin's main professional interest, but he was also endlessly captivated by the people of South America and of the other lands touched by the Beagle. The fascination was often reciprocal.

On the first night we slept at a retired little country-house; and there I soon found out that I possessed two or three articles, especially a pocket compass, which created unbounded astonishment. In every house I was asked to show the compass, and by its aid, together with a map, to point out the direction of various places. It excited the liveliest admiration that I, a perfect stranger, should know the road ... to places where I had never been. ... I was asked whether the earth or sun moved; whether it was hotter or colder to the north; where Spain was, and many other such questions. The greater number of the inhabitants had an indistinct idea that England, London, and North America, were different names for the same place; but the better informed well knew that London and North America were separate countries close together, and that England was a large town in London!

He encountered a good deal of skepticism, too.

My geological examination of the country generally created a good deal of surprise amongst the Chilenos: it was long before they could be convinced that I was not hunting for mines. This was sometimes troublesome: I found the most ready way of explaining my employment was to ask them how it was that they themselves were not curious concerning earthquakes and volcanos?—why some springs were hot and others cold?—why there were mountains in Chile, and not a hill in La Plata? These bare questions at once satisfied and silenced the greater number; some, however (like a few in England who are a century behindhand), thought that all such inquiries were useless and impious; and that it was quite sufficient that God had thus made the mountains.

An exchange that left me perplexed is the following, which happened during a long ride across the Brazilian country:

On first arriving, it was our custom to unsaddle the horses and give them their Indian corn; then, with a low bow, to ask the senhôr to do us the favour to give us something to eat. “Anything you choose, sir,” was his usual answer. For the few first times, vainly I thanked providence for having guided us to so good a man. The conversation proceeding, the case universally became deplorable. “Any fish can you do us the favour of giving ?"—"Oh no, sir."—"Any soup?"—"No, sir."—"Any bread?"—"Oh no, sir."—"Any dried meat?"—"Oh no, sir.” If we were lucky, by waiting a couple of hours, we obtained fowls, rice, and farinha. It not unfrequently happened that we were obliged to kill, with stones, the poultry for our own supper. When, thoroughly exhausted by fatigue and hunger, we timorously hinted that we should be glad of our meal, the pompous, and (though true) most unsatisfactory answer was, “It will be ready when it is ready.” If we had dared to remonstrate any further, we should have been told to proceed on our journey, as being too impertinent. The hosts are most ungracious and disagreeable in their manners; their houses and their persons are often filthily dirty; the want of the accommodation of forks, knives, and spoons is common; and I am sure no cottage or hovel in England could be found in a state so utterly destitute of every comfort.

Rather than a cultural barrier, this seems to be a case of self-entitlement and ingratitude on the part of the travelers, not a lack of hospitality. Couldn't they offer proper payment instead of "timorously hinting" things? It's hard to judge without the full context—maybe that kind of hospitality was universal and taken for granted everywhere else in the world?—but this smells like a case of the British arrogance of the time (more on that in the next episode).

At least, not all social hurdles were fraught with resentment. Once, in New Zealand, Darwin asked an aboriginal chief to let him hire a local man to act as his guide across the plains, at which the chief heartily offered to guide him personally. Darwin appreciated the help, but the chief had quite the personality:

Although the scenery is nowhere beautiful, and only occasionally pretty, I enjoyed my walk. I should have enjoyed it more, if my companion, the chief, had not possessed extraordinary conversational powers. I knew only three words: "good," "bad," and "yes:" and with these I answered all his remarks, without of course having understood one word he said. This, however, was quite sufficient: I was a good listener, an agreeable person, and he never ceased talking to me.

Still, so many of the naturalist's descriptions of people are about unmitigated merriment and good spirits, like in this episode in St. Domingo:

It happened to be a grand feast-day, and the village was full of people. On our return we overtook a party of about twenty young black girls, dressed in excellent taste; their black skins and snow-white linen being set off by coloured turbans and large shawls. As soon as we approached near, they suddenly all turned round, and covering the path with their shawls, sung with great energy a wild song, beating time with their hands upon their legs.

Or that charming evening in Tahiti:

In returning in the evening to the boat, we stopped to witness a very pretty scene. Numbers of children were playing on the beach, and had lighted bonfires which illumined the placid sea and surrounding trees; others, in circles, were singing Tahitian verses. We seated ourselves on the sand, and joined their party. The songs were impromptu, and I believe related to our arrival: one little girl sang a line, which the rest took up in parts, forming a very pretty chorus. The whole scene made us unequivocally aware that we were seated on the shores of an island in the far-famed South Sea.

I can almost hear them singing!

Oh, the Wonders!

No journey would be worthy of that name without a good dose of the sense of wonder. Darwin, like every scientist worth their salt, had plenty of it. Indeed, he experienced all facets of wonder, from awed curiosity...

[Near the Peruvian city of Lima] I had an opportunity of seeing the ruins of one of the ancient Indian villages, with its mound like a natural hill in the centre. The remains of houses, enclosures, irrigating streams, and burial mounds, scattered over this plain, cannot fail to give one a high idea of the condition and number of the ancient population. When their earthenware, woollen clothes, utensils of elegant forms cut out of the hardest rocks, tools of copper, ornaments of precious stones, palaces, and hydraulic works, are considered, it is impossible not to respect the considerable advance made by them in the arts of civilisation.

...to the feeling of astonishment:

It is necessary to sail over this great [Pacific] ocean to comprehend its immensity. Moving quickly onwards for weeks together, we meet with nothing but the same blue, profoundly deep, ocean. Even within the archipelagoes, the islands are mere specks, and far distant one from the other. Accustomed to look at maps drawn on a small scale, where dots, shading, and names are crowded together, we do not rightly judge how infinitely small the proportion of dry land is to the water of this vast expanse.

So many times, throughout his book, Darwin claims to be at a loss for words to describe how he felt. Here is a small sample:

It is easy to specify the individual objects of admiration in these grand scenes; but it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, astonishment, and devotion, which fill and elevate the mind.

Following a pathway I entered a noble forest, and from a height of five or six hundred feet, one of those splendid views was presented, which are so common on every side of Rio. At this elevation the landscape attains its most brilliant tint; and every form, every shade, so completely surpasses in magnificence all that the European has ever beheld in his own country, that he knows not how to express his feelings.

Who when examining in the cabinet of the entomologist the gay exotic butterflies, and singular cicadas, will associate with these lifeless objects the ceaseless harsh music of the latter and the lazy flight of the former,—the sure accompaniments of the still, glowing noonday of the tropics?

When quietly walking along the shady pathways, and admiring each successive view, I wished to find language to express my ideas. Epithet after epithet was found too weak to convey to those who have not visited the intertropical regions the sensation of delight which the mind experiences.

The naturalist was an eloquent guy, though, and he often did find the words he needed to express his delight. And delight he found everywhere he went. I will conclude this post with three of my favorites.

In the tropical jungles of Brazil—this was very early on, one of the first times he was mind-blown by what he saw:

The elegance of the grasses, the novelty of the parasitical plants, the beauty of the flowers, the glossy green of the foliage, but above all the general luxuriance of the vegetation, filled me with admiration. A most paradoxical mixture of sound and silence pervades the shady parts of the wood. The noise from the insects is so loud, that it may be heard even in a vessel anchored several hundred yards from the shore; yet within the recesses of the forest a universal silence appears to reign. To a person fond of natural history, such a day as this brings with it a deeper pleasure than he can ever hope to experience again.

In Mauritius:

Some of the views where the peaked hills and the cultivated farms were seen together, were exceedingly picturesque; and we were constantly tempted to exclaim "How pleasant it would be to pass one's life in such quiet abodes!"

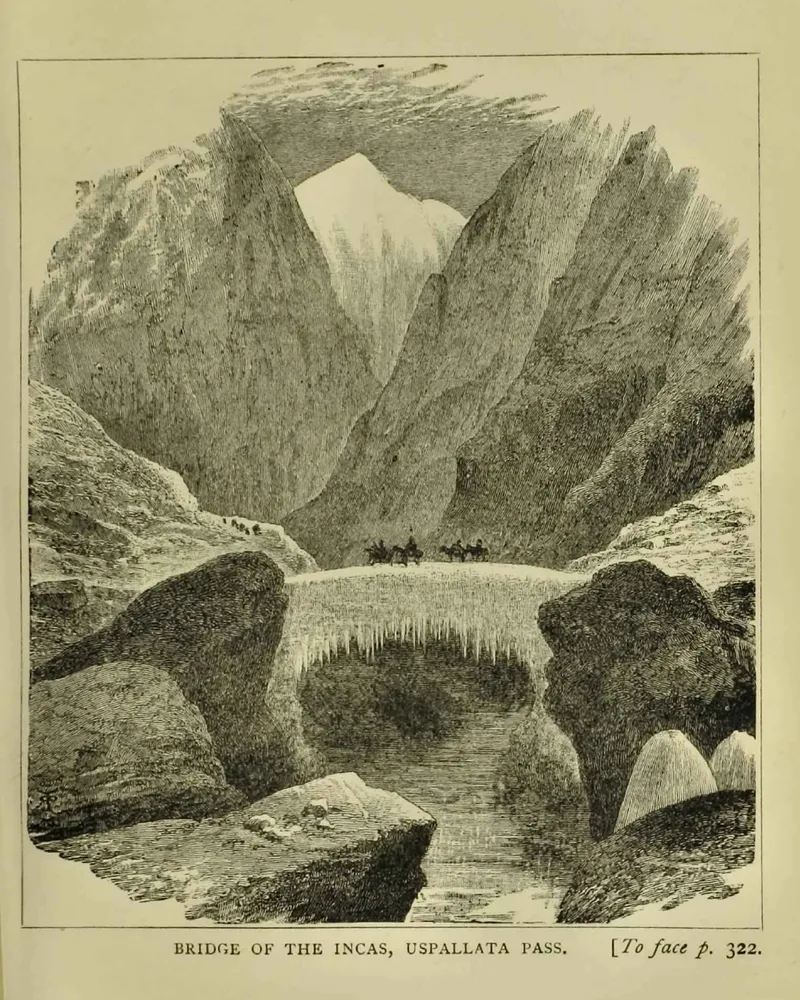

And in the Southern Andes:

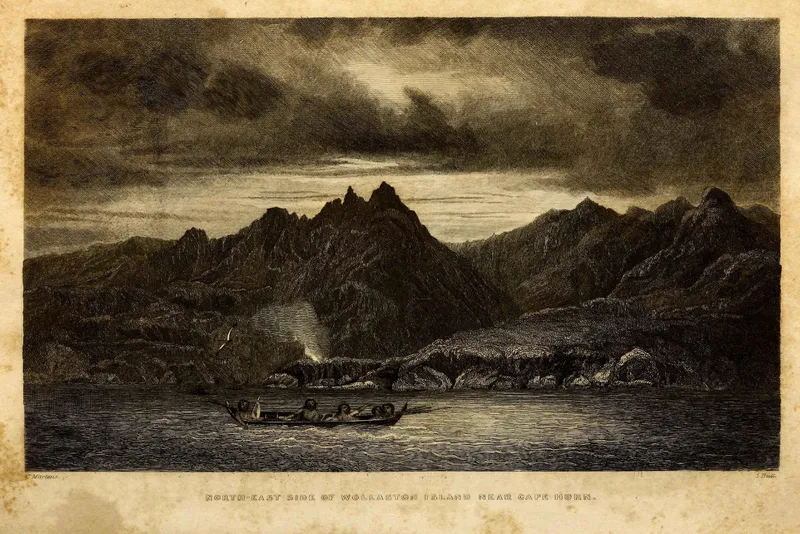

In these wild countries it gives much delight to gain the summit of any mountain. There is an indefinite expectation of seeing something very strange, which, however often it may be balked, never failed with me to recur on each successive attempt. Every one must know the feeling of triumph and pride which a grand view from a height communicates to the mind. In these little frequented countries there is also joined to it some vanity, that you perhaps are the first man who ever stood on this pinnacle or admired this view.

What a voyage! I can see why those memories became something he "would not exchange for twice ten thousand a year." Despite his difficulties in fully conveying his experiences, I think it was generous of him to share so much of his adventurous travels with us, his readers. ●

Next: In His Own Words Ep. 3 - Darwin the Man of His Times

Cover image:

Map: Der sudliche Theil von Sud-America, Adolf Stieler, 1831