I Witnessed the Birth of a Tiny World

How the mind creates and improves its framings on the fly

Marco Giancotti,

Marco Giancotti,

Cover image:

Photo by Kaitlin Duffey, Unsplash

This post is part of my List of Introspective Descriptions. I'm always accepting "curious introspection" links and submissions from everyone, regardless of the kind of inner experience covered.

Also: This blog now has comments! You can add yours at the end of the page.

To think better, you need to understand how thought works. That's easier said than done, but there are gentler ways to get started. For example, you can do worse than figure out what the building blocks of thought are like, and how they emerge, evolve, and die.

This is what I'm doing on this blog when I write about "framings" (and their little siblings, "mental models"). But it's one thing to theorize about them, and another to see them in action, real-time. It's like learning to ride a bicycle: a couple of minutes on it teach you more than a whole textbook could. If you can learn to notice how your mind uses framings in your everyday life, it will be hard for you to un-notice it. But everyday life is busy, multitasking, and chaotic. It's hard to stop and take an hour or two in an isolated, contemplative state to observe what your mind is doing.

So, earlier this week, I gallantly did that for you.

This wasn't exactly planned. I simply happened to find myself in the right conditions to see my thoughts in action, with no distractions and plenty of time to mull over it all.

As some of you know, I have aphantasia—no mental images, no "picturing things" in my head—and I've been offering my brain to neuroscientists for fMRI experiments, hoping to help shed light on this unusual way to think. When I wrote Boxed, I had been in the MRI machine for a total of about 30 hours. The tally is now well over twice that. While inside that big and noisy box, I've done all sorts of tasks: watching thousands of random images pass in front of my eyes, solving memory puzzles, listening to stories being read, watching movies, and so on.

This week I had another 3-hour session, and I realized, midway through, that while doing the actual experiment I could also learn something about what my mind does while working. A meta-experiment, if you will.

What I found turned out to be simple, but still quite illuminating. That's the topic of this short post.

The Setup

The experiment was as follows.

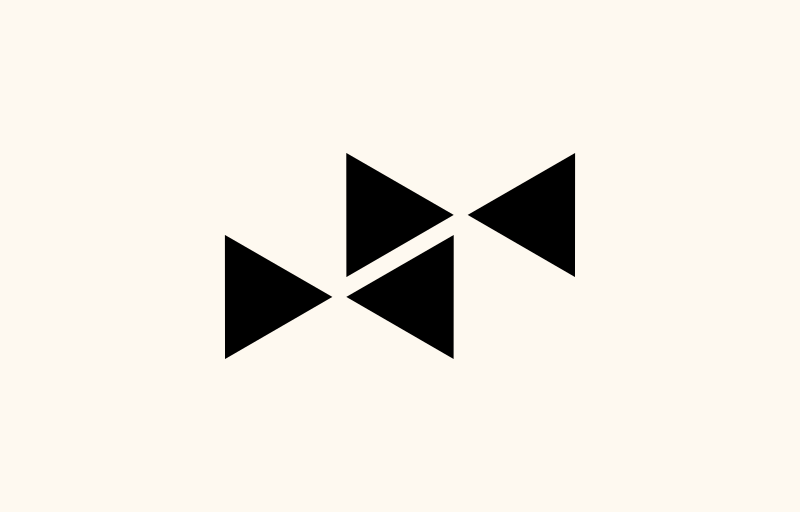

- While lying in the MRI, I'm shown an image made of triangles arranged in a specific way.

- After a few seconds of looking at it, the image disappears and I stare at a blank screen for about 8 seconds.

- Then I hear a beep, which means it's time for me to "picture" the same image again with my mind's eye. During this time, the screen remains blank, and I'm supposed to mentally project the image onto it as accurately as possible: the size, the arrangement and orientation of the triangles, whether they were black or white, etc.

- Then the next image comes, and everything is repeated.

- Many.

- Times.

In short, a cycle of "see → wait → imagine".

Now, having aphantasia means that I never "see" anything at all in my mind, which is precisely why I'm doing this: to see what goes on in my brain while I try.

But I also have abysmal memory (I think this is connected to aphantasia, but I'm not sure). Unless I use the special tricks I'm about to explain, I tend to forget the last image in those eight or so seconds between the moment it disappears from the screen and the moment the beep tells me to imagine it again. I go, "was it a big black triangle, or four small white ones?" (It is a tad embarrassing.)

This poor memory is nothing new to me, so during tasks like this I do what all aphantasics do: I unconsciously use alternative strategies to make up for it. Instead of toiling to conjure images that won't come, I talk to myself. In the case of this experiment, I convert the image into words while I'm still looking at it, then I repeat those words to myself a few times until it's time to try (and fail) to mentally replicate the image. (This "talking to myself" doesn't involve any "mental sounds", but that's a story for another day.)

This week's experiment was mind-numbing and not exactly exciting. But it proved to be the perfect setup to witness a simple framing popping into existence.

The Birth of a Framing

Take this image:

The first time I saw this, I described it to myself as "two pairs of triangles, each pair pointing at each other".

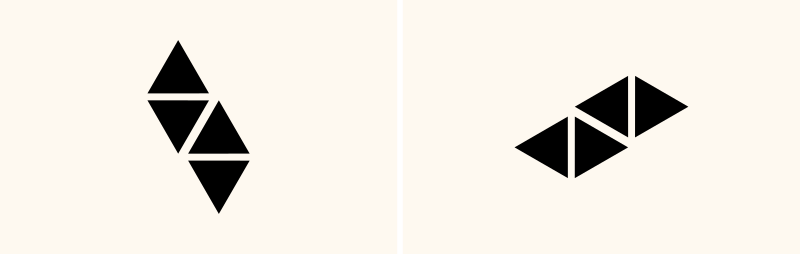

Then this other one came up,

and I realized I had to make my descriptions more complex to distinguish the two images. I expanded it to "...each pair pointing at each other vertically/horizontally", depending on the case.

But this wasn't great, because those rather long and complicated descriptions are cumbersome and easy to fumble. If I get distracted for a moment (especially likely after a couple of hours in the MRI), I might mis-repeat a detail and end up playing a solo telephone game, possibly screwing up the experiment.

So my descriptions evolved. After a while, I realized I had simplified the description of the first image to "two hourglasses", and the second image to "two bowties". These analogies are shorter, easier, and more evocative. I was able to use them because there were no other arrangements that looked anything like those two objects. But the important thing is that these neat naming ideas came to me instinctively. It seems to be a built-in capacity of the brain.

After a few repetitions, my descriptions further simplified into just "hourglasses" and "bowties" (plural), because I realized that they always came in pairs anyway, so there was no need to specify the number "two" every time. By the end of the experiment I was just repeating to myself "black bowties," "white diamonds," "white hourglasses"...

In other words, my mental framing for this task changed as follows:

| Phase | Black Boxes | Virtual Physics |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Images are novel | "triangle" | Can appear in any number and size, each oriented in any direction and at any distance from the others |

| 2: Some patterns emerge | "hourglass", "bowtie", "diamond", ... | Each can appear in small numbers, with fixed orientation |

| 3: A few fixed patterns confirmed | "hourglasses", "bowties", "diamonds", ... | Each always appears only as a pair with fixed orientation, never mixing |

This is as simple an example of mental framing as they get.

In these images, the "moving parts" comprising the framing—I call these black boxes but a psychologist might simply call them concepts—are the ontology I chose: the things that I assume to exist in the context of the task.

Also part of the framing are the ways those moving parts can arrange and orient themselves with respect to each other (the Virtual Physics). This is all that's needed to define a "tiny world", a restricted reality in which mental models can be created to make predictions and simulate events. That tiny world is the framing.

Like everyone else, I go through this kind of process constantly while awake, but this is the first time I had the chance to analyze it so closely. Isn't it strange? How does this work? I think the answer has to do with compression and meaning-making.

Compression

As you can see in the table above, my framing gradually acquired more black boxes (from just "triangle" to several names), and at the same time its Virtual Physics became simpler—from "triangles can do basically anything" to "each composite object always appears in the same way in an image".

The tiny world I created in my mind to remember what I had seen grew in variety, but its Virtual Physics shrank. By coming up with names for those objects, I was drawing new boundaries to streamline my mental models.

When I started writing this post, I hadn't realized that this is what happens, but it makes sense. Perhaps it is easier for our brains to store lots of pre-built archetypes for things—e.g., people, objects, ideas—each known to do only a few things reliably, than it is to track undifferentiated "particles" that can mix and interact in an infinity of ways.

When you turn a large file into a smaller zip archive, the operation your computer does is called compression. In rough terms, it works by finding predictable patterns in the file's binary sequence, like big swaths of repeating zeros or ones, and replacing them with a description of that pattern: compression algorithms essentially do a (much) more clever version of replacing "000000000" (a sequence of nine zeros) with "9x0" (a shorter way to convey the same thing).

The idea that data can be compressed is central to computer science, but it extends well beyond machines and email attachments. In particular, it is well known that the brain uses compression to cope with the enormous amount of data that flows in all the time from the senses, as well as to manage internal processes like decision making. But that's for the low-level neural encoding of raw sensory information. What about higher-level "thoughts"?

Here the science is still fuzzy, but there are indications that some form of compression happens even in the "language of thought", closer to consciousness. It seems like the hourglasses-bowties framing I developed in the MRI is another case of the same process: as I noticed more patterns on the screen, I progressively compressed the information into reusable components, and managed to express in a single word what had initially taken many words to describe, and as a result succeeded in memorizing those funky arrangements.

Meaning

The compression approach seems to have worked well enough for me, but how did I do it? What criteria allowed me to converge on those few black boxes for my framing? An even better way to ask that question is this: what guides the drawing of meaningful boundaries?

I answered this in the final episode of my Purpose series on Plankton Valhalla: I could only do it because I had a goal in mind—to correctly remember and distinguish those arrangements for the sake of the experiment.

That goal naturally led to a distinction between what is meaningful and what isn't. By looking at many images, I (mostly unconsciously) noticed that there were some differences that made the difference for my goal, and chose new boundaries and names to capture those.

Most differences did not make a difference for my goal, though: potential orientations and positions of the triangles that never occurred, the exact spacing between triangles, etc. These were meaningless in that context, so the new names I chose didn't capture them. I didn't need to create categories for "hourglasses with 3-millimeter necks" or "diamond triplets", because those differences, although present or possible in theory, never mattered or occurred in the dataset. I locked those irrelevant details up in my newly named black boxes, and allowed myself to disregard them.

This was me making meaning, guided by a clear goal.

Now think about the things in your life that involve novelty: things like reading a book, meeting new people, having a conversation, learning to paint. In all these activities, you are presented with new sensory information that may initially overwhelm you. There are too many moving parts, too many details that may or may not be relevant, and it seems like anything could happen. You are in the "it's all triangles" phase.

Then, as you spend more time doing whatever you're doing, your compression system kicks in: you find patterns, recurrences, fixed forms, and begin treating them as special. You may give them new names, or find analogies with things you're already familiar with, or simply treat them implicitly as "things" of their own—you don't need a special name for "the curious way white paint mixes with cobalt" for that pattern to start "being a thing" in your mind.

All of this is always a function of the goal you have at the time. Different people, with other goals, will do the same things but form different framings from yours. That's how you end up talking past each other, or puzzling at the strange ways some people seem to think. You rarely realize that you're each living in a different tiny world. ●

Cover image:

Photo by Kaitlin Duffey, Unsplash

Comments

Loading comments...